Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Reflections on Weightlifting at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

We have just concluded what will hopefully stand for some time as one of the strangest Summer Olympic Games ever. The change of date due to a worldwide pandemic; the enforced lack of a public audience at events; medalists draped their awards around their necks; the entry list of countries and athletes was highly unusual; the list goes on.

In reflecting on the overall results of weightlifting in these Olympic Games, allow me to share a few personal observations.

Background

As the NBC Sports statistician for our sport my duties are rather simple. We don’t have a great deal of “stats” as one finds with sports like baseball or tennis. When on site in the past (Atlanta, Sydney, Athens) I was seated with the announcers and the producer, easily able to chat back and forth over details. In more recent years (Beijing, London, Rio), I have been in the broadcast booth with the announcers. Through a window, we have the producer immediately alongside in a separate area. In these situations, I have utilized a small grease board to note important facts about an athlete, a lift, or events unfolding on the field of play.

This year was different. Because of the Covid situation, the broadcast booths had been reconfigured, with separation between the play-by-play announcer (Ed Cohen) and the analyst (Cheryl Haworth). My space had been eliminated, but I was located across the hall in a room dedicated to statisticians. I was in contact with the team via headphone set.

Some Observations

- Early on it seemed clear that Italy had made a strong effort to improve their lifting results. This observation was reinforced a few days in with an online article to this effect. Five athletes (three male, two female) returned home with two bronze and one silver medals. The men finished in fourth place for country ranking; USA was third.

- Only two nations, China and the United States, fielded full (eight person) teams. That was largely due to the use of “Robi points” by which athletes were ranked throughout the qualifying period.

- A great number of lifters appeared to, or did, “black out” during the jerk portion of the C&J. This seemed to occur more often than one might generally observe in a meet of this quality. What’s going on here to cause such an apparent increased frequency?

- The chalk box is now located on the opposite side of the stage from the athletes’ stairway, something reportedly encouraged by the world of television within recent years. I’m not sure it makes sense otherwise.

- The women created no new world records but did manage to create 25 Olympic records.

- The men created five world records and 30 Olympic records. The Olympic marks are not a surprise, since the latest new bodyweight categories were in effect. “Standards” for each new category had been calculated and posted. A blog on the topic of the ever-changing bodyweight categories is in the SportsEdTV weightlifting library.

- The absence of a greater number of world records could be a result of several things, including limited team size, exclusion of many countries and/or lifters, possibly tighter anti-doping regulations always present at Olympic Games, or something else.

- Recent anti-doping headlines related to the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) and the future of our sport may have had an effect on this year’s performances. In the C&J portion of the competition, rather than committing fully during the clean, numerous lifters performed only a deadlift. There were a number of examples where lifters struggled, or failed, in the recovery from cleans. Some of this, at least in my experience, suggests expectations of stricter drug testing may have had an effect on performance.

- The continued, and frequent, distraction of a “Jury review” during lifts in question was a routine part of this Games. This is confusing to the lay public and TV viewing audiences, the former of which was absent this year. But one must consider, if the referees are not competent to officiate, they should be replaced. If the Jury has a better vantage point or their use Video Playback Technology (VPT) with Dartfish’s slow-motion and/or stop action playback is to be the determining criteria for a lift’s success or failure, maybe it’s time for a new system of judging. This ability to override the referees is something new, and it does not sit well with many observers.

Know the Rules

It helps for athletes and coaches alike to be extremely familiar with the technical rules for weightlifting. There were several instances in Tokyo that illustrate this need.

- As has become more common in recent years, a great number of lifts suffered from what was always announced by the speaker as “press out.” We have a couple of blogs available on this subject:

https://sportsedtv.com/blog/press-out-what-the-rules-say-what-the-jury-says/

https://sportsedtv.com/blog/the-jerk-adapting-to-todays-overzealous-officiating/

- Although all were lumped into press-outs, several actual different rules applied, including bending and extending of the arms during recovery, incomplete extension of the arms, and true press outs. There were other infractions, small and large that seemed to confuse lifters or their coaches. Many times, the athlete’s coaching support staff, with a less than perfect view of the lift or the rule violation, were quick to utilize the new “challenge card” issued to each country at weigh-ins.

- Elbow or arm contact with the knee(s) or thigh(s) during a clean is an old rule violation. When two or three referees see such an infraction and flip their choice to a red light, the system activates the “down” horn before a jerk attempt can be made. As I watched the international feed on a monitor, one male lifter sure looked like his right elbow touched the knee, so the down signal did not surprise me. However, he continued to successfully jerk, then held the weights longer than needed, and finally, after returning the barbell to the platform, wagged a finger toward the officials that their three red light decision had been in error. The Jury, using Dartfish video analysis, played the lift back from several angles and determined the lifter was correct. The referees’ decision was reversed, and the lifter was awarded the lift.

- I made notes of at least one lifter clearly not placing her feet parallel to one another prior to receiving the down signal in the jerk. This has always been a violation of the rules, and the lifter is not to receive a down signal (especially in the “modern” referee judging system) until proper alignment is made. But you know what? The referees are located quite low (so as to avoid blocking an audience view) and they cannot see the feet.

- More than one lifter had an otherwise successful lift turned down for lowering the barbell before the signal. USA lifter Katherine Nye’s first snatch, passed by the referees, was cancelled by the Jury when it was determined she clearly released the bar above the shoulders. Coaches need to train lifters to 1) wait several seconds before dropping weights in training and 2) eliminate the modeling effects often seen from non-lifters (high school kids, CrossFitters, etc.) when weights are simply dropped from overhead or the shoulders.

On Making Attempts

Unlike the World Championships and most other competitions, at the Olympics a lifter must make at least two attempts, one in each discipline, in order to total or receive a medal. Bomb-out in the snatch, and no C&J attempts are allowed.

I have always hammered home that no one gets a medal for their chosen starting weight. With the current 1kg increment between lifts, an athlete may end up doing essentially three nearly 100% attempts with little rest between efforts. If a lifter has trained for this, great. If not, one may be challenged to perform optimally.

Georgia’s Lasha Talakhadze (+109kg), started after all his competitors had finished, made all of his lifts, broke all the world and Olympic records, and gained the gold medal. Never did his coaches resort to the common local stalling tactic of “Stop the clock; add 1kg. Stop the clock again, add another kilogram.” He just did what was needed within the allotted time.

Thinking back to my first international assignment, I recalled working with a lifter who had started training and competing under my guidance. Three years in, this lifter made it to the junior world championships. On his day of competition, he was successful on all six attempts, ending with personal records. Keep in mind, increments in those days were in multiples of 2.5kg, with a 5kg jump required between first and second attempts.

When we returned to the hotel that evening, I heard another member of our team relate to my lifter one of the dumbest-ever lifting comments; “It’s not your fault that they held you back.” Held back? Gimme a break!

For greater statistical reliability on attempt success, I chose to look at the only two full teams, China and the United States. In women’s lifting China made 22 of 24 attempts (92%) while USA was successful with 13 of 24 attempts (54%). In men’s lifting, China were successful with 16 of 23 attempts (70%), while USA equaled their female teammates with 13 of 24 successful attempts (54%).

Build on Success

Succeeding with an attempt puts pressure on the competition; missing a lift provides an opening for others to quickly move ahead, especially with today’s 1kg rule. To paraphrase the great American World War II general, George S. Patton, a key to success is to “Make the other poor dumb #*@+*&! miss his (or her) lift.”

One might win the Olympics with only one successful snatch and one successful C&J, but it doesn’t happen often. As we continue on this topic, anyone with a cursory knowledge of statistics knows that correlation is not cause and effect. That said, I decided to look from several angles at some of the numbers associated with the Tokyo weightlifting competition.

- There are plenty of reasons why a lifter might make or miss a lot of lifts. With today’s closer total numbers, many lifters, once on the scoreboard, may sit back, wait to see how others finish, then take jumps to move ahead. Often, many of these last-ditch efforts result in failure. This is noted in the Tokyo results.

- After securing the gold medal, some lifters took large jumps while chasing a record. One winner passed up the final attempt. Both scenarios occurred throughout the categories and placings in Tokyo.

- As far as bomb-outs, three women in “B” sessions failed to total; six “A” session lifters were DNF (did not finish). For the men, all 10 bombs occurred in “A” sessions.

- Often medals and placings are determined by a lifter’s last C&J. Looking only at third attempt C&Js among women who totaled in the “A” sessions, 19 of 56 (34%) made good final lifts. Interestingly, of these successful third attempt jerks, 12 (63%) were performed by medalists.

- Checking only third attempt C&Js among men who totaled in the “A” sessions (but including M73kg “B” session winner Abdullah, who ultimately finished third), 19 of 55 (35%) lifts were successful. Interestingly, of the 19 good third attempt jerks, 11 (58%) were performed by medalists.

- Gold medalists in Tokyo made a lot of lifts, succeeding with at least four of six attempts. One male winner made three of five attempts, declining his last C&J. Four Olympic champions succeeded with all their attempts. Gold medalists made 66 of 83 attempts, averaging 80% success.

- Silver medalists did nearly as well, averaging 76% success. One runner-up male lifter made only two attempts, while all the others made between three and six lifts. Again, some big jumps and/or failed attempts may be related to “going for gold.”

- Bronze medalists made 56 of 84 lifts, averaging a success rate of 62%. The range of their successful lifts was from two to five.

Entry Totals Determine a Lifter’s Session

The IWF tweaked the starting list until the final weeks before competition. Much of this was due to eligibility requirements centered around anti-doping issues. The final roster included 98 males and 96 females. Two women scratched due to injury.

Currently available on the International Weightlifting Federation’s website is the Tokyo 2020 Results Book. Incorporated within is the Start List Package, a document made available prior to the start of competition. This shows the sessions to which lifters are assigned, along with a good deal of other competition details. Here the IWF lists each athlete’s so-called Entry Total (ET).

An ET is important due to the current “20kg Rule” for both genders. This rule stipulates that, at weigh-in, the sum of one’s stated opening attempts must be within 20kg of the previously declared Entry Total. (Not surprisingly, I noted an exception or two)

This approach discourages a common practice some years ago when countries might inflate their lifters’ totals in order to gain entrance into the more prestigious “A” session. Keep in mind, back in those “good old days” larger “A” and “B” groups existed.

Often, a lifter with an inflated qualifying total failed to reach a high-level of performance. If the “A” session is only for the best lifters (especially since greatly reducing the number of participants in order to provide the audience an exciting competition of the likely medalists), the question arose, “How did this also-ran get in here?”

Upon reporting to work each morning, I always checked and recorded the “B” session results. On Wednesday, July 28 it was obvious to me that the M73kg category “B winner” (Abdullah, INA) could be a factor at the end of the day, so I advised our broadcast team of the possibility. Our producer, David Bruner, located footage of this lifter in case we needed to highlight Abdullah as a medalist. I also did a little research on this lifter and concluded his Entry Total of 320kg, the same as three others in his group, had perhaps been fudged downward a bit in order to deliberately place him in the “B” session.

This was not the first time this tactic has been used. The question remains: why seek to lift in the “B” session? The obvious answer is less pressure. But, importantly, there is a new twist to all of this. Under the current rules, the lifter who makes a lift or total first places ahead of those that later equal that performance. Lifting in the “B” group, Abdulla totaled 342kg, well in excess of his ET of 320kg.

Lifting in the “A” session, Calja of Albania totaled of 341kg and figured he had the bronze. Post-competition media reports stated that he and his coaches had been unaware of Abdullah’s performance. Calja would have needed a success with 2kg more in his last C&J in order to move into third. During the “A” session at least the top three “B” session results are posted on the scoreboard. Coaches, pay attention!

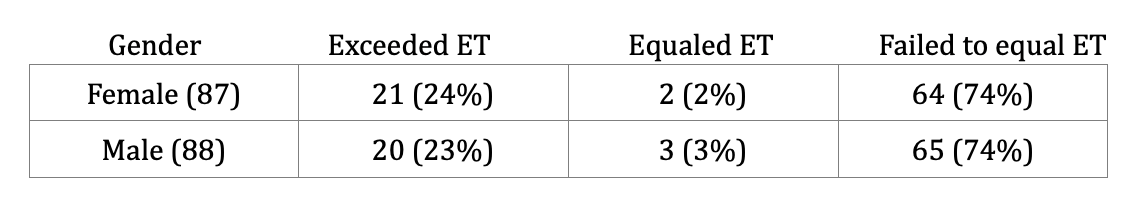

Curious about the Entry Totals versus performance, I tabulated the ET vs. the final total. This table represents only lifters that totaled; those 19 that bombed out were not included. No doubt some lifters bombed in attempting to meet their Entry Total.

Very similar performances, right? While this information might be of general interest to some, I dug a bit deeper and found the following to be more engaging:

- Five female gold medalists exceeded their ET (Hou, Diaz, Kuo, Dajomes, Li)

- One female gold medalist equaled her ET (Wang)

- One female gold medalist totaled within 1kg of her ET (Charron)

- Six male gold medalists exceeded their ET (Li, Chen, Shi, Lyu, Elbakh, Talakhadze)

- One male gold medalist equaled his ET (Djuraev, 87kg)

This may not mean anything. If you’re good enough to be in the medal race, you’re good enough to be in the “A” session (if this is chosen), and there’s no need to inflate the Entry Total. A few other notes:

- Aside from Wang, who equaled her ET, all of the Chinese lifters totaled more than their Entry Total.

- Checking listed ETs, it became obvious that only two Chinese women (Wang, Li) and one Chinese man (Shi) had the highest ET listed in their respective bodyweight categories.

- Only three of seven women winners (Kuo, Wang, Li) had the highest ET in the category on the Start List. The same number of male winners (Shi, Djuraev, Talakhadze) had the highest ET in their respective categories.

- Of the 21 female medalists, eight exceeded, two equaled, and 11 were under their listed ETs. Of the 21 male medalists, 10 exceeded, one equaled, and 10 were under their listed ETs.

Instead of inflating the ET in order to get into the “A” session (and there were several fairly obvious examples of this), it appears some medalists may have listed totals lower than their best. If nothing else, this takes pressure off a stated first attempt, whether taken or adjusted.

Conclusions

Again, none of this suggests cause and effect. It can be helpful, however, to look at trends. For those interested, download and peruse the IWF’s Result Book and dive into the numbers. Allow me to repeat, there are no medals awarded for starting high. Making attempts puts the pressure on the competition; attempting unlikely weights creates additional pressure on the lifter choosing such a tactic. It’s your choice.