Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Why Change Weightlifting’s Bodyweight Categories … Again?

Have you been jonesing for that state record that is just out of reach? Well, the tides have again turned, and this may be your best opportunity to ink your name in the record books, albeit in a new bodyweight category.

Effective last November the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF), the worldwide governing body for the sport of weightlifting, announced a new bodyweight category scheme for both men’s and women’s competitions. For newcomers to the sport, one may ask: Why? What was wrong with the former designations?

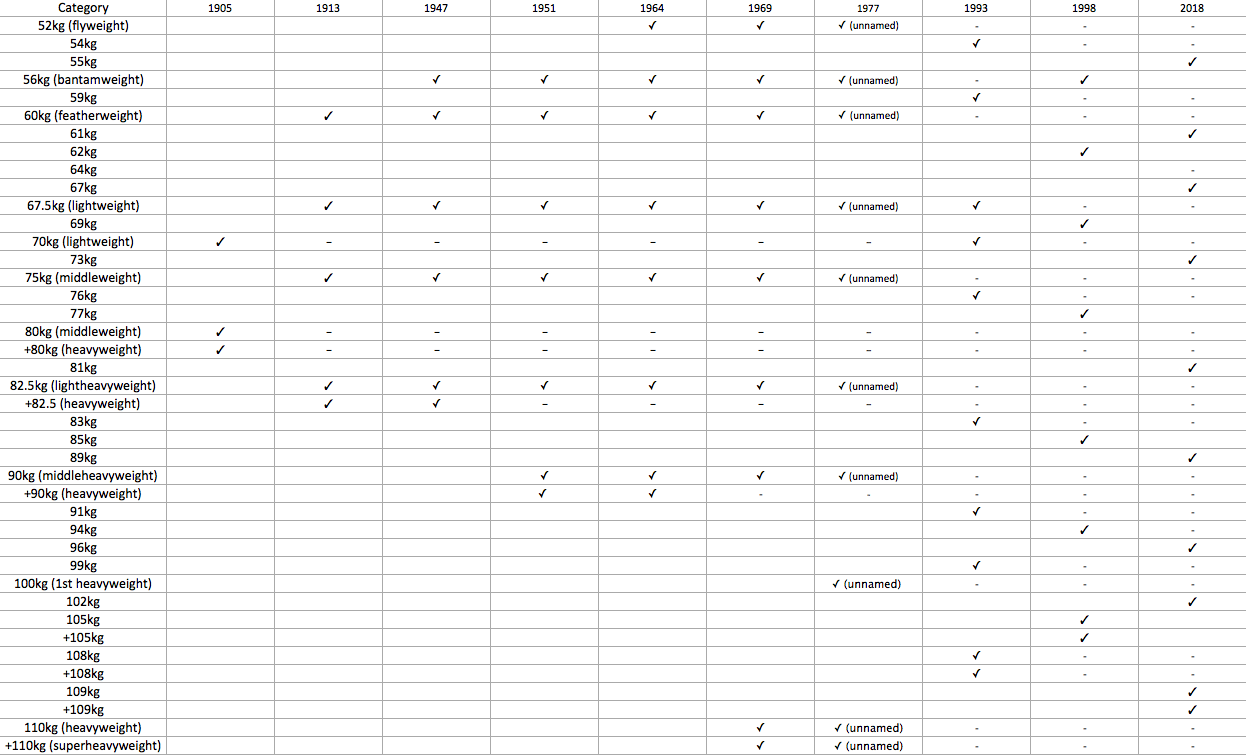

Take a look at the history of men’s bodyweight categories in weightlifting since 1905. Blank spaces mean the category did not exist at that time; a hyphen indicates that a former weight class no longer exists. A checkmark indicates the category was available that year.

Mirroring boxing, weightlifting originally utilized bodyweight category names (lightweight, middleheavyweight, etc.) for many years. The names were dropped after the 1976 Olympics, although the media hangs onto the title, superheavyweight. We now use simply the metric numerical designations. Interestingly, although Jimmy Carter was unsuccessful in getting Americans to adopt the metric system during his presidency, weightlifters have taken fairly easily to this “foreign” concept. We weightlifters seem relatively conversant with kilograms.

A quick check indicates that USA National Championships have been conducted in kilograms from 1970 or so. Of course, not every local meet director had access to kilogram sets, so it took another 10 or so years before most results were posted metrically.

Why Change the Classes?

Changes in weightlifting’s technical rules aim to improve the sport. Recognizing an audience will watch intensely for only a limited amount of time, meet conduct has been sped up due to the changed “1-kilogram rule” and reduced time between attempts. Adjusting the bodyweight categories also seeks to improve the sport, but the motives may seem a bit opaque.

During my lifting career I witnessed numerous additions to the weight class line-up, such as the 52kg, 100kg, and 110kg categories. Relative to these latter two, I wish the change had come sooner! I faced the daunting challenge of considering the move from the 90kg class to +90kg (or superheavyweight).

Years ago, obtaining the votes necessary to add a new bodyweight category often revolved around geographic considerations. For instance, the 52kg class was favored by the Asian nations, while the addition of the 110kg (and later, 100kg) categories favored Europe and the Americas.

No longer do we see such a democratic solution. World Weightlifting, No. 145, page 48 simply states, “After 20 years the IWF decided that it is high time to change the structure of weightlifting’s bodyweight categories and established a new set of categories for both genders.”

From 1985 through 1988 I served on the IWF’s Scientific & Research Committee. At a committee meeting prior to the Seoul Olympic Games in 1988 the IWF first floated the idea of changing the bodyweight categories. The initial argument evidenced inconsistent increments between classes, with a range of about 7% (52 – 56kg) to 13% (60 – 67.5kg).

OK, I thought, that makes some sense; maybe this is a good idea.

But the “wink-wink” reason from wanting to modify the weight classes, some of which had been on the books since 1913, was related to the prevalence of anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) use that contributed to greater world records.

As a harbinger of things to come, during the late 1980s the IWF became sensitive to the sport’s future Olympic involvement. A quick review of the following 20-year timeline provides food for thought:

-

In 1968 the International Olympic Committee banned the use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs)

-

At the 1970 World Championships nine lifters tested positive for amphetamine use. Initially stripped of their placings and medals, all were reinstated.

-

In 1976 the IOC introduced AAS testing

-

In 1983 improved mass spectrometer testing replaced the earlier radio-immunoassay method for detecting AAS

-

The 1988 Seoul Olympic Games provided new challenges for weightlifting (and other sports)

The IWF recognized this “shot across the bow” as evidence of greater scrutiny of our sport. Changing bodyweight categories might be a solution to the problem. Five years after the idea was initially discussed we saw the first major overhaul of bodyweight categories take place in 1993.

However, and perhaps not surprisingly, world records continued to rise.

How Many Times Will the IWF Do This?

In 1998 the IWF once again adjusted the categories, and again, world records continued to rise. Now, after 20 years of relative stability, the IWF wants to mix things up again.

A good deal of public discussion suggests the sport of weightlifting remains close to the edge in terms of possible elimination from the Olympic Games due to continued PED violations. Currently, the sport appears guaranteed inclusion in Tokyo 2020 and Paris 2024. Certainly, the IWF continues to promote a message to the general public that our sport leads the way relative to anti-doping testing.

Drastic measures have been taken in recent years to grab the attention of countries that have proven to be repeat offenders. Continued anti-doping violation by certain countries has restricted their team size for next year’s Olympics. Many of these countries are often present on the podium.

Accordingly, we find weightlifting back at the same scene, namely, let’s again change the classes, establish world “standards,” and see how long it takes to have new records.

Athletics (track and field) continues to have a similar problem with positive doping results. However, they have not changed the 100-meter sprint to the 95- or 105- meter sprint, a move that would freeze existing world records and create new ones.

True, the javelin had to be redesigned in 1986 (distances thrown endangered audiences!).

But the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) has not changed the weight of the shot or discus, despite a dearth of world records in these events. The men’s world outdoor shot put record was the last set in 1990; the men’s discus world record was set in 1986. Competition continues and champions are crowned, but these world records seem unlikely to fall any time soon.

One wonders, could the IWF ever accept the presence of lower records, possibly reduced drug use, and equally tight competition?