Weightlifting, Mental Health

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Are You Training Your Positive Mental Attitude (PMA)?

Within these pages we have offered a fair amount of content related to the physical aspects of weightlifting technique and training. Another important ingredient in weightlifting success has yet to be addressed: the mental, or psychological, aspects of our sport.

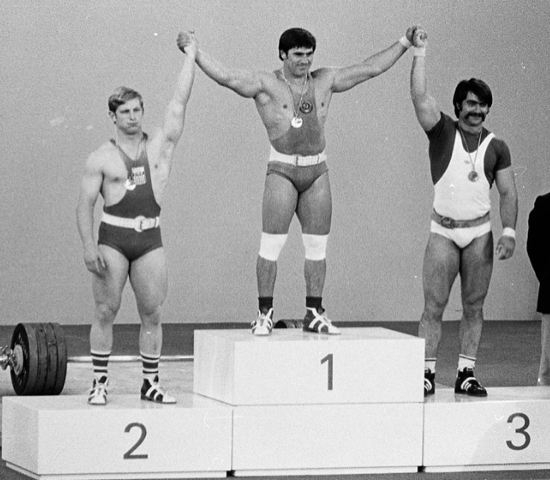

In weightlifting, as in many other sports, the performance differences reflected by medalists on the podium are sometimes quite small. This has been particularly true since the introduction of the “1-kilo rule” in 2008. This rule change encourages totals in closer proximity to one another than during the previous era when lift increments were multiples of 2.5kg.

At the 2019 World Weightlifting Championships, second place lifters totaled on average 97% (male) and 96% (female) of the winners. Even third place lifters’ totals (95% for males, 94.1% for females) were quite close to the winning performances. This finding reinforces the often-observed conclusion that the smiles of the winner (happy to be champion) and the bronze medalist (happy to be on the podium) may contrast with the often lack of smile on the silver medalist who realizes how close victory was.

Photo credits: Bruce Klemens

Mental Ingredients of Success

Lifting success includes many physical variables (strength, power, flexibility, genetics, etc.). The other side of the equation revolves around mental, or psychological, variables associated with sporting success. The development of a positive mental attitude (PMA) has often been reduced to three “D’s.”

First, a lifter must have DESIRE. Not everyone that dreams of making an Olympic Team accomplishes that goal. But, one can be certain that no one makes an Olympic Team without a burning desire to do so.

Second, DISCIPLINE is needed for success. Both training appropriately and living a sensible, clean lifestyle, are necessary. Not skipping workouts, making it through that last set of squats, constantly striving for improvement… all these things reflect discipline. We all know lifters with great potential that never made it very far, often due to a lack of discipline.

Third, DEDICATION is a must. I well remember one Christmas day in the 1980s at the Colorado Springs Olympic Training Center. Although many of the resident lifters had returned home for the holidays, some remained in the dorms. We also had married, non-residential lifters who lived in town. There had been a large snowfall on Christmas Eve, but the next day was a scheduled workout. I drove my VW bus (fortunately a decent deep snow vehicle) to the Center and managed to get to Bldg. 23, where I found national champion Val Balison, a married father of two. He and I had to shovel our way into the weightroom, but the workout took place. Val was the only lifter to show up that day. That’s dedication!

Today vs. the Past

Many may not know that the weightlifting competition protocol has changed remarkably over the years. In my early days of lifting, no time limit existed between attempts. In 1963 I timed Joe Dube, (1969 World Champion) as he paced behind the platform for seven minutes prior to a successful junior world record press attempt.

Today, readers can easily find online recordings of lifters from earlier times. It’s readily noted that lifters were not constrained by a time limit, and their psychological preparation methods often dragged out, usually, like Dube, pacing behind the platform.

Reports from the 1960 Rome Olympics mention lifting (one bodyweight class, no split sessions) starting at 10:00 a.m. and not concluding until well after midnight! “Something must change!” came the cry of sporting officials. At the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 we first see the new three-minute clock displayed on the platform. This time interval between attempts was instituted in order to speed up lifting meets. Still, with three minutes we frequently see a lifter taking time to mentally prepare either at the back of the platform or while standing over the bar.

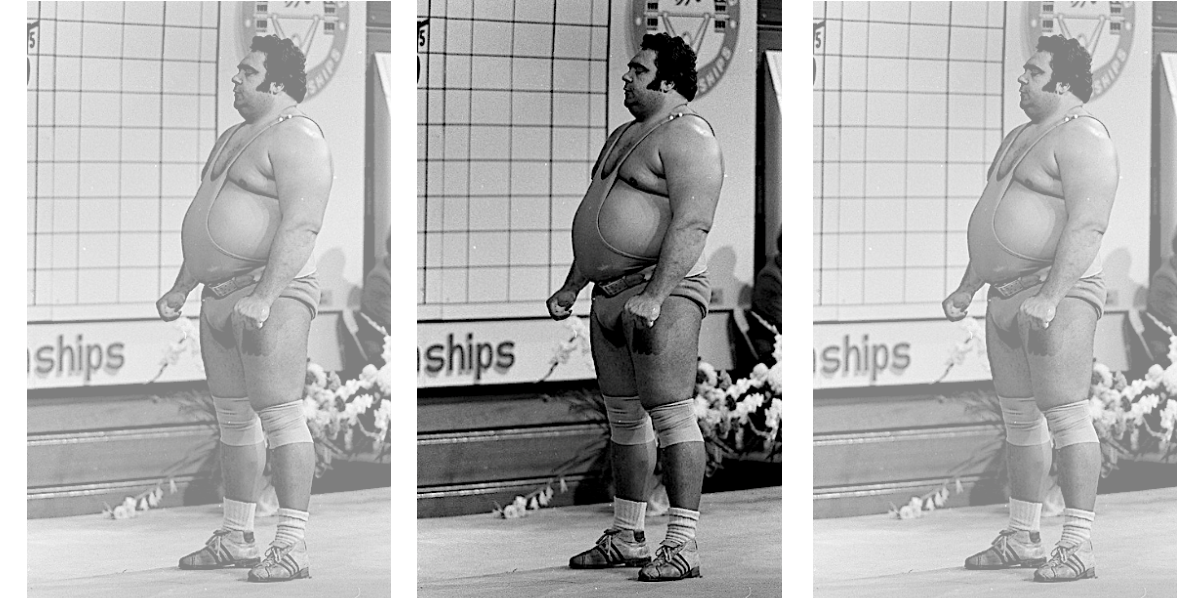

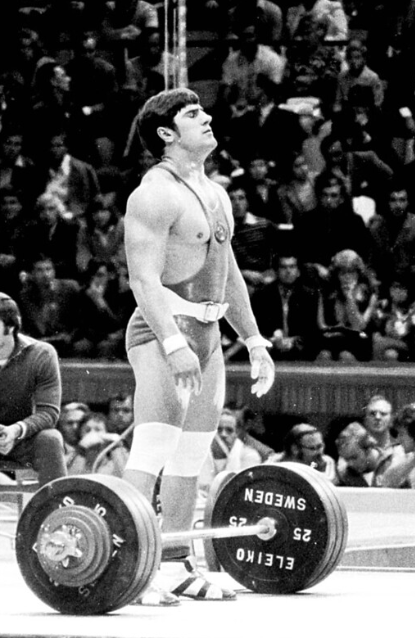

Note the Bruce Klemens picture of eight-times World and Olympic Champion Vasili Alexeyev used here. The champion has eyes closed while concentrating before an attempt at the 1978 World Championships. An ABC-Wide World of Sports commentator suggested that Alexeev appeared to be asleep standing up. Yet in Dmitry Ivanov’s book, The Strongest Man in the World, the champ states at least twice that he wanted his pulse at 108 beats per minute (18 beats in 10 seconds) prior to a lift. Anything less, he drank coffee to further elevate the pulse.

Is he excited? Certainly, but not in a distracted way. No huffing and puffing, no calls for the audience to cheer him on, no slapping himself or other theatrics as we often see today. With a three-minute interval Alexeyev had plenty of time to rally his motivation and confidence, including visualization of a successful lift.

In more recent times the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) recognized that, like other forms of entertainment, an audience is likely to maintain interest for two to three hours. Give the audience a compact program (10 lifters in an A session) that is easily followed in terms of who is winning, and spectators love the sport. Thus, splitting a weight category into different sessions was established, followed by lowering the interval between attempts steadily from three minutes to two, and finally now to one minute (when following another lifter).

This change in the preparation time between attempts requires a totally different psychological approach for today’s lifters versus those from earlier eras. There simply is not time to prepare after mounting the platform with the clock running down. Mental rehearsal must occur while waiting backstage for one’s next attempt. Most lifters continue to sharpen their mental efforts while standing over, or grasping, the bar, awaiting the loud 30-second timing buzzer. This buzzer (another relatively new development) may serve otherwise as a distraction.

How is Your Mental Training?

Champions have been known to state that winning is largely mental, rather than physical, with an unscientific 90% figure often mentioned. When there are no major differences in the strength and/or power characteristics between competitors, then yes, mental attitude may be a defining property.

On the competition platform winning lifters often outlift others capable of exhibiting greater strength, perhaps measured by squatting or massive training hall lifts. But ours is not a total strength sport; power and the ability to effectively execute these technically challenging lifts at the right time are keys to top performance.

If we agree that the mental game is so important, do you devote adequate time to this part of performance preparation? And, importantly, what skills are needed, and how does one practice these skills? The usual skills mentioned include such things as self-confidence, appropriate arousal, imagery (or visualization), and the ability to concentrate.

Early Attempts

When I took up the position of USA Weightlifting’s first national coach in 1981, I was determined to expose the resident lifters at the Colorado Springs Olympic Training Center to at least some rudimentary techniques of relaxation and visualization. The goal was to improve focus and concentration skills.

Prior to making the move to Colorado I had served for five years as a senior counselor at a residential drug treatment center where we routinely instructed relaxation methods to our residents. Effective use of meditation and yoga during my own years on the platform had convinced me of the value of these skills.

Our OTC lifters had little to do besides eat, sleep, and lift. They had plenty of time to work on psychological skill improvement. Attempts to have our residents involved in either educational or vocational pursuits did not receive great support from the sport’s leaders of the day. My model of training was influenced by an early Soviet weightlifting “yearbook” that outlined about 29 hours of weekly focused training, be it with the barbell, in general physical preparation, in recovery, or sports medicine pursuits. This seemed like an adequate amount of time for our lifters to devote to improved performance, but certainly this could not all be physical effort.

Several lifters took advantage of the opportunity to work on their psychological skills. Volunteers met in our training hall, the USOC’s former Building 23, our rather Spartan location that we gradually built into a fully functioning training room (but not nearly as nice as the one later formed in the 1990s).

A few days each week were devoted to about 30 minutes learning to relax, to turn off muscular tension, and to focus on breathing. Soon thereafter we began working on visualization, imagining oneself first moving toward the platform, then addressing the barbell, and finally, successfully executing the lift with proper technique.

Next Stop: The Elite Athlete Program (EAP)

By 1982 the US Olympic Committee, wishing to have good results in the upcoming Los Angeles Summer Olympics, identified a handful of sports where focused scientific effort was expected to pay big dividends. Fortunately, weightlifting was one of the sports chosen. We put together a team that included Dr. John Garhammer (biomechanics), the USOC Sports Science Department and Dr. Michael Stone (physiology), and Dr. Michael J. Mahoney (sport psychology).

At the time, Dr. Mahoney was at Penn State. Fortuitously, Mike was also a dedicated weightlifter, having competed in his younger years and eager to not only contribute the EAP success, but also to sharpen his skills on the master’s platform. He put together a team that included Drs. Andy Meyers and Bob Weinberg.

Mike Mahoney spent a lot of time dealing with athletes on a one-to-one basis. Typical of applying sports science to athletes from different backgrounds and capabilities, it seemed some lifters really took to Mike’s involvement, while others shunned the opportunity to learn more.

At one point, Dr. Mahoney placed a sensory deprivation tank (think, Altered States, a 1980 movie) in our facility’s back room. A few of us (myself included) took advantage of the opportunity to further explore the inner workings of the mind.

Basically, if a lifter is effectively using visualization and has a positive mental attitude (PMA), there may be no need for assistance from a sports psychologist. But these skills are not necessarily intuitive; it is for those athletes unfamiliar with such psychological tactics that professional assistance may be beneficial.

Photo credits: Bruce Klemens

It is beyond the scope of this blog to describe in detail the finer points of psychological preparation but review the SportsEdTV’s blog library for more content on this subject. A lot can be learned from the approaches taken by athletes in other sports. Think of the imagery work we see at the Winter Olympic Games when skiers go through their final visualization before departing of start house.

SportsEdTV have a great team assembled to share their professional wisdom related to the mental aspects of improved sports performance. Check ‘em out!