Strength And Conditioning, Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Triple Extension: What’s It All About?

Are you sometimes confused by some of the exotic-sounding terms related to weightlifting and the general activity of lifting weights (weight training)? You’re not alone; both activities share the capability of confusing the lay public with oft-repeated jargon.

Many times the jargon is totally inappropriate. For example, in the early days of weight training (before exercise-specific equipment) it was not unusual to read in a “muscle mag” of someone performing a prone press when it more properly should have been called a supine press. Today this exercise is more easily understood as a bench press since a bench is involved. Although a prone press (actually a push-up) requires similar muscular action to a bench press, early adapters erred in ignoring positional specificity.

Another good old example was calf raise. Beginning with the toes elevated on a board and the heels below the toes, one moves from ankle dorsiflexion to ankle plantar flexion. While the primary calf muscle, the gastrocnemius, contracts, it does not detach (“raise”) from its anchors. This exercise is better known today as a heel raise, as the heels do, in fact, move up and down during exercise execution.

Want to confuse friends with more jargon examples? Suggest a Romanian deadlift, which is actually one of four versions of the stiff-legged deadlift available since the earliest days of weightlifting. The new title tells us little, while the original label actually explains much more.

Another example is a reverse leg curl, first labeled as such in the 1960s. That name pretty much explained the action needed. But it gets more confusing with the introduction of specific equipment and more exotic titles like Nordic curl, or the evidently slightly different muscular action of a razor curl. But you can really wow your friends with a reference to the very similar glute-ham-gastroc exercise!

Of late there’s been a good deal of chatter about weightlifting’s triple extension. This somewhat mystical, almost exotic sounding, phrase draws a blank from the lay public. What’s the big deal? More importantly, how did we get to the point of debating whether or not triple extension takes place during the snatch or the C&;J?

Triple Extension Takes on an Identity

Until the 1960s the technical rules for the snatch and clean required a lifter to avoid contact of the barbell with the body prior to the bar reaching its final position. As with today’s technique, at the end of the first pull, the barbell reaches the height of the knees. In days of old, the barbell moved upward when the lifter extended (straighten or move to a 180° of extension) the hip joint in a mostly rotational action. This action was similar to the motion used for a good morning exercise, another jargon-inspired evolution from the former bend-over exercise. Perhaps the reader is beginning to see a pattern of moving from simple, well-defined terms to mysterious ones, begging for an explanation from those in the know.

Anyway, a modern pulling technique now involves greater use of the lower body to push the barbell upward during the second pull. As early as 1974 USA National Coaching Coordinator Carl Miller wrote an often-overlooked article, The Pull is Not an Extension. Basically, Miller suggested that the modern pulling technique was a summation of vertical, rather than rotational, forces. While having a profound influence on many coaches and lifters, Miller was often scorned by other influencers in the sport.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association was formed in 1978. Early pioneers often emphasized the then relatively new sport of powerlifting (squat, bench press, deadlift) as the best way to “strength” train. After a few years, the NSCA leadership approached the head of USA Weightlifting intent on exploring a move toward more explosive, power-producing, training.

Credit these early NSCA efforts for the introduction of the terms triple extension and power position (the end of what weightlifters refer to as the transition phase of pulling). Over time these terms caught on and have become so popular as to earn a spot in USAW coaching materials. Neither term had previously been part of a weightlifter’s lexicon. Certainly, triple extension well describes the coordinated muscular action that includes an extension of the ankle, knee, and hip joints during a vertical jump, the explosive second pull phase of a snatch or a clean, or the drive portion of the jerk.

Triple Extension Sequencing

Without getting too carried away, consider that most joint movement experienced by weightlifters is either flexion or extension. A person standing erect is considered to have fully extended knees and hips. Lean slightly rearward and the hip joint extends a bit farther. Rise on the toes and one has plantarflexed (extended) the ankle joints.

Early published works on the modern pulling technique suggested that hip extension should occur as the final part of the ankle-knee-hip sequence. Hip extension as a final force results in the lifter leaning backward slightly, often with the shoulders behind the toes. This hip extension causes a slight forward barbell trajectory at the top of the so-called “S pull.”

Today we see many lifters extend the hip early, prior to the second pull. Here the torso is perpendicular to the platform. Often this lifter’s heels are not flat on the platform, as conventional wisdom previously dictated. This posture results in a second pull that appears as a strong hip thrust. Such a hip thrust, accompanied by a strong backward-leaning posture (greater hip extension) may result in the barbell being a significant distance from the torso during the pull-under phase, leading to overhead control challenges.

Triple Extension for Everyone?

Closely examine weightlifting’s competitive lifts and one quickly sees how the strength coach world might sing the praises of this type of training. By adding an external load (the barbell) to muscular action (triple extension, as in jumping or pushing off the ground) that occurs on the playing field or court, and one could expect to have a stronger, more powerful athlete.

But troll around the internet long enough and one encounters arguments by online experts as to whether the triple extension action is even part of modern-day weightlifting technique. Some advocate for, while others advocate against, this action. Does any of this really matter, or do we run the risk of wasting time debating a topic for which one can find evidence on both sides?

If we can for a moment forget all else (barbell trajectory, moving under the bar, etc.) but the definition of triple extension (see above), what can we conclude?

Do Most Lifters Triple Extend?

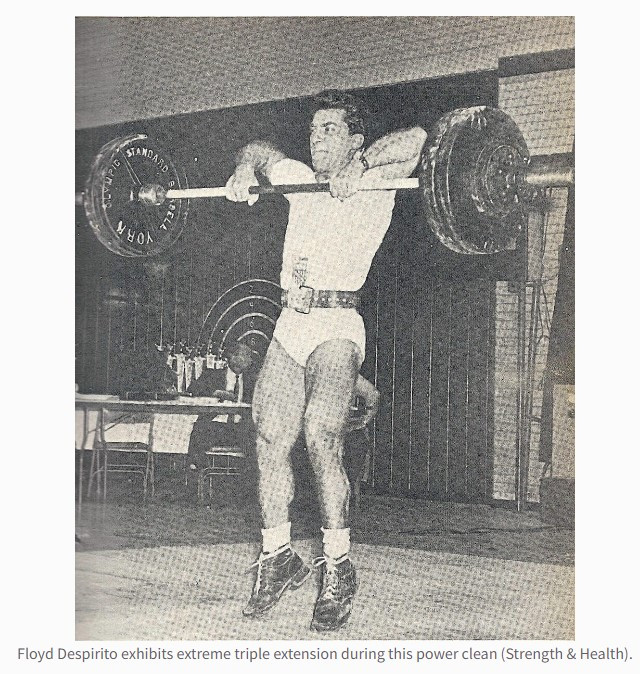

The easy answer is, yes, most lifters triple extend at the top of the second pull, and certainly in the drive portion of the jerk. If the heels are higher than the toes, the ankles have plantarflexed (extended). If the knees are approximately locked the knees have extended. At the top of the pull the hip is at full extension. Note this appearance in the following pictures.

|

| Triple extension is easily viewed with frame-by-frame video analysis. The lifter starts in a triple-flexed position and moves into extension at the end of the second pull. This is the standard proximal to distal muscular firing that all advocate. |

It is an established fact that the greatest power production in elite lifters occurs at the end of the second pull. Performed properly, the second pull creates a maximum force against the barbell. At the top of the second pull, most lifters appear to be triple-extended. Similar to a vertical jump, triple-extension is a natural movement related to elevating the barbell and repositioning the feet to receive the bar either overhead (snatch) or on the shoulders (clean). But the triple extension posture is not critical to lifting success.

The sport of weightlifting is not judged subjectively, so several variations in technique may be successful. The important factors related to getting the bar into a proper receiving position are power production during the second pull and how quickly (efficiently) the lifter repositions into a receiving position under the still-rising weights.

Do Some Lifters Not Triple Extend?

In the clean, three-time USA Olympian Kendrick Farris often does not plantarflex at the top of the second pull. This was very noticeable at the 2011 and 2012 USAW National Championships. When asked about this apparent lack of ankle plantar flexion Kendrick replied simply that his clean weights were relatively light, the power produced adequate, so instead of attempting to further elevate himself and the weights, he chose to pull under. Keep in mind, at the time Kendrick had reportedly cleaned 218kg in training. His first attempts were about 91% effort, a load hardly requiring maximum pulling force.

At other times, depending on the weight on the bar, Kendrick does rise on the toes. He also always triple extends during the snatch.

Three-time Olympic Gold Medalist Kakhiashvili is another example of a lifter who sometimes does not sharply extend the ankle joints. There’s an online clip of him winning his first gold in Barcelona in 1992 when lifting for the “United Team” (former USSR) that shows he clearly plantarflexed onto his toes during the second pull. By 1999, now winning the World Championship title for Greece, he does not rise on his toes. Is this a new, deliberate technique? Unlikely. He’s simply doing what is required to make the lift.

Too Much Emphasis on Triple Extension?

It is important for weightlifting coaches to avoid an overemphasis on a lengthy triple extension. During a snatch or clean the lifter must quickly transition from the explosive second pull to the pull-under phase. Without a quick, fluid switch the lift is often doomed to failure as the bar “crashes” on the lifter, either overhead (snatch) or in the rack (clean).

Such “stalling out” at the top of the second pull often cancels the opportunity for a quick recovery or results in red lights (bending and extending of the arms in the snatch, elbow touch to knees in the clean) from the officials. The longer a lifter stays in the triple extension position the more likely a missed lift will occur. It is an undesirable technique characteristic to exaggerate the triple extension posture.

This photo from the October 1965 Strength &; Health was used to illustrate the important concept of keeping the elbows pointed outward during the pull (in order to keep the barbell near the torso). Here the elbows look great, but one could argue that the lifter has focused more on pulling the bar high than in quickly racking the weights.

Lifters: Achieve Peak Power, Then Get Under the Bar!

As in a vertical jump, weightlifting’s peak power comes from a coordinated lower body effort to propel the barbell upward from the power position. Hopefully, readers realize that extreme emphasis on triple extension, or holding a triple extended position, is undesirable, at least in weightlifting.

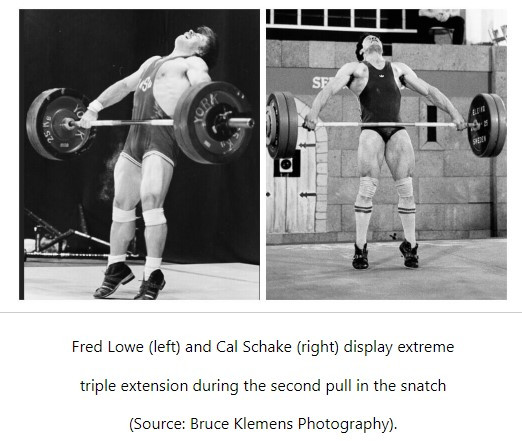

Here are two USA Olympians noted for their rather extreme triple extended position, especially during the snatch.

A lifter’s lifts are considered to be in balance when the snatch equals about 80% of the C&;J. Throughout his lengthy career, Fred Lowe excelled in the C&;J, repeatedly lifting in excess of 180kg. However, his best snatch performance was frequently lower than the approximate 80% of clean we might expect.

In 1982 Cal Schake (75kg category) became the heaviest American to snatch double bodyweight (152kg). Cal’s snatch exceeded 80% of the clean ratio, demonstrating his dominance in the snatch.

To reiterate, the important takeaway message for readers is that once peak power is obtained and the barbell moves with its greatest acceleration, it is time to get under the weights. The body’s descent begins while the barbell is still rising.

Strength and Conditioning Coaches' Use of Triple Extension

Gaining strength and power with external resistance (lifting weights) may be a worthwhile goal for non-weightlifters. But do these athletes need to learn to snatch and clean like a weightlifter? This is not absolutely necessary. Many S&;C coaches train weightlifting’s many derivative exercises, especially pulls (from various heights) without the need to go overhead (snatch) or rack the bar (clean).

Strength training with triple extension and added external resistance (barbell, medicine ball, etc.) makes sense, especially if the triple extension is present in one’s particular sport. Weightlifters and weightlifting coaches don’t need to fret about triple-extension. Lifters are not judged subjectively as to how well they triple extend. It may happen, or it may not, but it’s just not that big a deal.

S&;C coaches: the term triple extension came from your profession. Use it if it serves a purpose for your athletes.

We started off discussing the sometimes exotic Iron Game jargon. Based on a Google search the term triple extension appears to have taken on a life of its own. One may conclude that arguing back and forth over the importance of triple extension in lifting or in sports may not be the best use of one’s time. It just ain’t that complicated!