Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

The Elbow Joint in Weightlifting: Our Weakest Link?

A few years back Coach Clancy Benton contacted me with a question about the elbow joint. Basically, he wondered if a hyperextended elbow could be a positive or a negative influence on lifting.

We had several exchanges back and forth on the subject, much of which is worth discussing here at SportsEdTV. However, in order to further discuss this issue, we need to first explain a few of the terms used.

Terms Defined

Let’s cover the basic anatomical terms of joint flexion and extension as they relate to receiving weights overhead in the snatch or jerk. Using the old adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words” here are pictures of our key points:

Elbow

A flexed elbow (less than 180°) could be cause for red lights from the officials (incomplete extension of the arms):

This straight arm is an example of normal elbow extension (180°, a straight line) in the snatch:

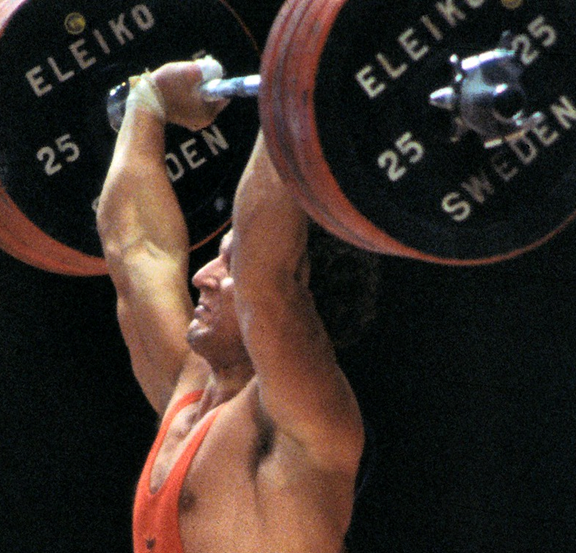

Next is what we consider to be a hyperextended elbow (beyond 180°) in the snatch:

Wrist

For the wrist, we consider only two possible positions, either extension or neutral. It’s impossible to hold a maximum weight overhead in wrist flexion, as the back of the hand would face the ceiling.

This photo illustrates good wrist extension (palm up, knuckles down) in the snatch:

By comparison, here is a fairly neutral wrist (palm forward, knuckles rearward) in the snatch:

This is a good wrist extension in the jerk:

And here is a neutral wrist in the jerk:

Shoulder

When discussing shoulder orientation in the final receiving position of a snatch or a jerk we consider the joint to be either externally rotated or internally rotated. With external shoulder rotation the elbow joint appears vertically aligned with the barbell. By comparison, the elbow joint appears in a more forward-rearward orientation when the shoulder is internally rotated.

This is an example of an internally rotated shoulder (snatch):

This is an externally rotated shoulder (snatch):

This is an example of an internally rotated shoulder (jerk):

This is an externally rotated shoulder (jerk):

Elbow Dislocations in Weightlifting

OK, basic terms have been defined.

As I told Coach Benton, I see no real advantage (or disadvantage) to an elbow that slightly hyperextends, although this position always seems a bit precarious, especially for those of us who have witnessed a number of elbow dislocations in the snatch.

The first such injury of which I was aware was America’s Bob Bednarski, who suffered a dislocation while snatching in the 1967 Pan American Games. Importantly, at least for relatively new lifters, is the fact that at that time, the press lift was five years away from its competitive abolishment. The press took up about 40% of a lifter’s training in those days, so “Barski’s” injury was not a matter of weak elbow extensors.

In the years to follow, numerous elbow dislocations took place with weightlifters from the local to the international level. Perhaps the greatest one-meet incident of elbow dislocations occurred at the 1981 World Championships, held in Lille, France. My recollection (as assistant team coach) is that of the 194 male athletes. We witnessed one shoulder and eight elbow dislocations.

Lille: Turning the Corner

There are several likely contributors to this high injury rate in Lille. Realize that the press had been eliminated nine years earlier and pressing was no longer a priority. Lifters did not include much specific training for their arms. Additionally, with greater specialization in the two remaining lifts, snatch and C&J records had undergone a rapid increase.

After the first few dislocations in Lille, the local organizers approached me (I’ve never been sure why) and asked if I could contact the bosses at Sweden’s Eleiko Barbell, the equipment supplier for that meet. No doubt the IWF and the local hosts were concerned about these injuries.

I knew enough French to converse with the locals, who thought the bar spun too freely. Within the previous year or so, Eleiko introduced several design modifications, including changes to the bar’s bearings. When catching a snatch or racking a clean the discs at this World’s did appear to revolve more easily than in the past. Read on to discover the likely cause of this excessive spinning of the discs.

I knew the two Eleiko chiefs, both of whom were due to come to Lille for the final categories. I sent a telex in English, explaining the organizers’ concern. Eleiko replied, asking if the bars had been left (loaded) in squat racks overnight. I assured them this was not the case.

The injuries continued, but I was not privy to additional talks between the IWF, the local organizers, and Eleiko.

Unusual Positions

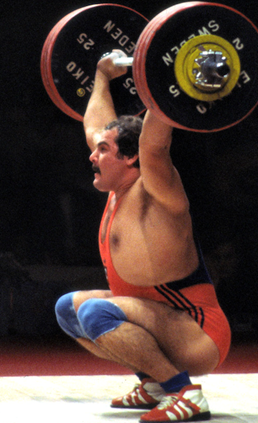

Lille was my first exposure to the Soviet Union’s Victor Sots (100kg) and Anatoli Pisarenko (+110kg). Both these lifters won their respective weight class, but I was most impressed with their flexibility, especially their snatch and jerk receiving positions (see externally rotated shoulder examples above).

Due to what I consider to be their outstanding flexibility their receiving positions reflected 1) an externally rotated shoulder, 2) well-extended wrists, and 3) an upright torso position. However, the elbow joints looked particularly vulnerable when seen from the side.

At the time I was unfamiliar with the terms internal or external shoulder rotation. Today, it’s easy to find numerous online discussions on the topic. Of course, some of these discussions get a bit carried away, such as one recent one that describes internal shoulder rotation as a “Chinese technique” versus the external rotation described as an “American technique.”

This is perhaps taking technique details a bit too far. Weightlifting is not gymnastics, diving, or figure skating, where “perfect” technique decides the podium placings. What lifters want is optimal technique for their particular body, segment lengths, and levers. There’s plenty of room for different technical points in our sport.

Further Thoughts on the Subject

The year after Lille, I was invited to address the President’s Council on Fitness and Sports at their annual meeting in Washington, DC. I took USA lifter Derrick Crass along to demonstrate our competitive lifts to an audience anticipated to be largely medical doctors.

Long before PowerPoint, I also loaded up a slide carousel of Bruce Klemen’s great sequence photographs of the 1982 World Championships in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. In particular, I chose a sequence of Sots and his new world record snatch.

For the better part of an hour, I lectured, and Derrick lifted. Thinking an audience of doctors might be interested in the topic, I mentioned the previous year’s elbow injuries in France.

With no medical background myself, I opined to the gathered audience that I had come to appreciate the Sots-type receiving position, especially for the snatch.

I’d spent much of the previous year considering what I’d seen in Lille. Many of the lifters at the Olympic Training Center with whom I closely worked were exposed to my greater emphasis on attaining a similar externally rotated shoulder position like that exhibited by Sots and Pisarenko.

To the gathered medical audience, I also mentioned that I considered the extended wrist (palms facing upward) position was crucial to safely snatching in this manner. I was quite surprised when a doctor in the front row spoke up in support of my premise. I was further surprised to learn that he was David Kennedy, MD, the Australian weightlifting team’s physician, and that he had studied the issue of elbow dislocations in weightlifters. A main finding in his work had been that the majority of those lifters that incurred an elbow dislocation tended to have heavily wrapped wrists that tended to prevent wrist extension.

Conclusions

- There is no absolutely right or wrong way to orient the upper body joints when hoisting a snatch or a jerk.

- We have champions and records from lifters using all of the options pictured above.

- Those with small hands, particularly females and/or youth lifters may be more likely to demonstrate a neutral wrists with the bar overhead.

- The great American three-time Olympian Kendrick Ferris always catches his snatch (pictured above) and jerk attempts with an internally rotated shoulder… and he’s had no injury as a result.

- For the most part, one is unlikely to execute a squat jerk with an externally rotated shoulder. Many Chinese male lifters squat jerk, but this does not make the internally rotated shoulder a “Chinese” technique.

- With a few exceptions, many internally rotated shoulders pair with neutral wrists.

- Elbow dislocations have occurred with all of the various orientations described in this writing.

Each of the numerous times I have run this subject by a medical expert the general consensus, especially for the snatch, is: an externally rotated shoulder, with extended wrists is a strong receiving position relative to the elbow. As the great Tommy Kono often said, a successful snatch is felt in the wrists.

Oh yeah…. about those rather free-spinning discs in Lille? Consider that from the earliest days of competitive lifting the York Olympic Standard Barbell model was often used in international competitions. York’s collar featured two tightening wing nuts opposite one another. Eleiko, first used in the 1958 World Championships, designed an attractive collar with both wing nuts on the same side, a boon for loaders. Credit USA coach Mark LeMenager with determining that the spin was likely related to the Eleiko collar design at the time and the new (reduced friction) bearings.

Check this short video clip to note the effects of the collar design in use some years ago. Eleiko has produced numerous other collar designs since, thus eliminating this particular issue.