Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Press-Out: What the Rules Say, What the Jury Says

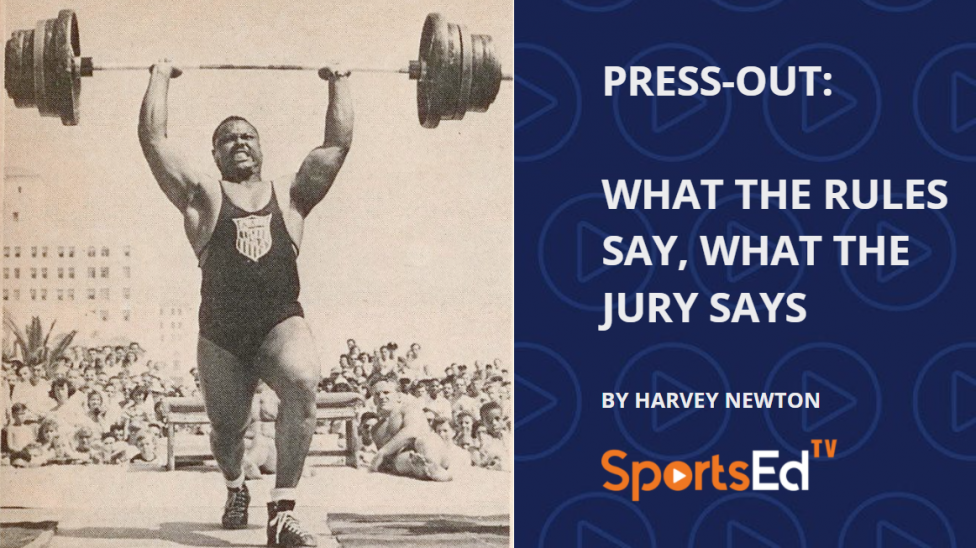

In recent years, we have often seen what appears to be an otherwise good snatch or, more likely, a jerk, turned down by the referees and/or the jury for what is all too commonly referred to as “press-out.” Olympian, and former USA Weightlifting president, Brian Derwin brought our attention to this matter in a blog last year. Brian offered some great training tips on how to train, especially the jerk, so as to avoid red lights from the referees.

What is press-out, a term in use in weightlifting circles for decades? Certainly, in the old days, press-out was much more acceptable, especially in the snatch, and most specifically, in the split style snatch. What has to happen to trigger a negative judgement from today’s technical officials?

Actually, there are several rules related to the topic of press-out in the 2020 edition of the International Weightlifting Federation’s Technical and Competition Rules and Regulations. Let’s review the details:

- Under general rules for the snatch (2.2.1) and for the jerk (2.3.2) the lifter must lift “… to the full extent of both arms… .”

- Under General Rules for All Lifts, 2.4.4 states, “An athlete, who, for any reason, cannot fully extend the elbow(s), must report/display this fact to all on-duty Referees as well as the Jury prior to the start of the competition…”.

- Under Incorrect Movements, 2.5.1.3 includes “Pause during the extension of the arms.”

- Again, Incorrect Movements, 2.5.1.4 includes “Finishing with a press-out, defined as: continuing the extension of the arms after the athlete has reached the lowest point of his/her position in the squat or split for both the Snatch and the Jerk.”

- Again, Incorrect Movements, 2.5.1.5 states “Bending and extending the elbows during the recovery.”

- Under Incomplete Movements and Positions, 2.6.1 confirms “Uneven or incomplete extension of the arms at the completion of the lift.”

What Do These Rules Mean?

Rules 2.2.1 and 2.3.1 do not require that the elbow joints fully extend (‘lock out’). But if the elbows do not fully extend, the lifter must snatch or a jerk so that his/her fullest elbow extension is as complete as anatomically possible. This is a subjective call by the judges.

Rule 2.3.3 was added many years back to deal with the possibility that one’s elbows do not fully extend. A few years ago, USA National Champion and world team member Jackie Berube told me that her inability to lock her elbows was an inherited trait, and that others in her family had the same issue. Jackie, like others in the same situation, made a point of indicating this issue prior to attempting a lift.

Bruce Klemens Photography

Jackie Berube’s inability to fully extend the elbows was a challenge for officials.

In Florida high school weightlifting, which is really a hybrid combination of powerlifting (bench press) and weightlifting (clean & jerk), it is not unusual to see a lifter present as not being able to fully extend the elbows while the hands are overhead. I have sometimes checked such a lifter by having them place the affected arm on my shoulder, palm up. I then gently push on their elbow from below. Surprisingly, many elbows reportedly incapable of fully extending overhead have no problem straightening in this posture. This is a simple matter of deltoid and upper back inflexibility, no doubt a result of a heavy emphasis on bench pressing.

Rule 2.5.1.3 presumes the lifter will continue to extend the arms. This is the true definition of press-out. Some lifters whose elbows have fully extended on previous attempts have been seen to hold a later lift on slightly flexed elbows without an attempt at further extension to full lockout. This then is a violation of Rule 2.6.1. This is another value call by the officials, but literally, no lockout (for one who can fully extend the elbows), no Rule 2.5.1.3.

Rule 2.5.1.4 is a relatively new addition, one no doubt included in order to further explain the English term press-out to an international audience. However, it is interesting when interpreting the rule literally. This rule suggests a lifter that catches a snatch or jerk on slightly flexed elbows but is not in their lowest squat or split position, could lower themselves deeper as long as the barbell is not further elevated. The lifter is not pressing the barbell upward but is pushing the body downward. I’m not sure this was the rule’s intent, and I seriously doubt many referees could tell the difference between a press-out and a press-down.

Rule 2.5.1.5 is the most likely situation to be lumped into the “press-out” violation rule. The playback process used for today’s jury allows these officials to watch, often in slow motion playback, the details of a lift. This is a benefit the referees sitting in judgment of each lift do not have. It’s been my experience that when the jury president presents the jury’s decision it is normally stated as a press-out. Bending and extending the arms during recovery is not a press-out as defined by Rule 2.5.1.3. And what if the “bending and extending of the arms” occurs at a point in the lift other than during recovery?

Rule 2.6.1 is fairly clear-cut.

Today’s Situation

As Brian so aptly titled his blog, it appears to many of us long-time weightlifters that today’s officials often appear a bit overzealous in ruling against lifts that would have otherwise succeeded in years past. As an IWF Category I referee I must admit that I have not sat in on a recent technical rules clinic held prior to competition. Maybe what appears as today’s overly strict enforcement (compared to years past) of any elbow “wobble” is red light worthy.

Certainly, the overall officiating environment has changed in recent years. This is especially true in the United States where multiple platforms are utilized in order to accommodate the larger entry lists encouraged. Five platforms in place? Well, at least 15 referees are needed. That’s more referees in one session than we often saw in one day at a national meet a few years back.

How are more officials enlisted to serve? The call has gone out, including incentive plans to bring in a more diverse officiating population. Modest cash incentives are available for those that otherwise volunteer to serve. Special support consideration for certain groups is aimed at encouraging more participation.

Many new referees, both nationally and internationally, have been enlisted. In order to obtain a certification as an official these folks have sat through rules clinics, taken a test, and been scrutinized by more veteran officials. That all sounds great, but one question repeatedly pops up, namely, has this person ever lifted? It’s not a prerequisite to have been a lifter, but one may wonder if the person in the official’s chair has ever struggled to keep a lift overhead. Weightlifting experience, or lack thereof, may be related to how quickly a non-lifting official may be to flip on a red light for something that does not fully meet the current rules related to press-out.

There are a number of rules that fall under the umbrella description of press-out, but as we’ve seen, a well-informed official really needs to be able to separate out the differences that exist, follow current trends, and do their best to remain objective while judging lifts. Sitting in one of those three seats, especially when a five-person jury is sitting behind, can be an uncomfortable experience. When assigned a position other than the center seat, I always opted for that seat (#1 or #3) located on the same side as the jury.

Might as well have the same view they have, right?