Strength And Conditioning, Swimming

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Strength Training for Swimmers: Improve Performance, Power & Speed

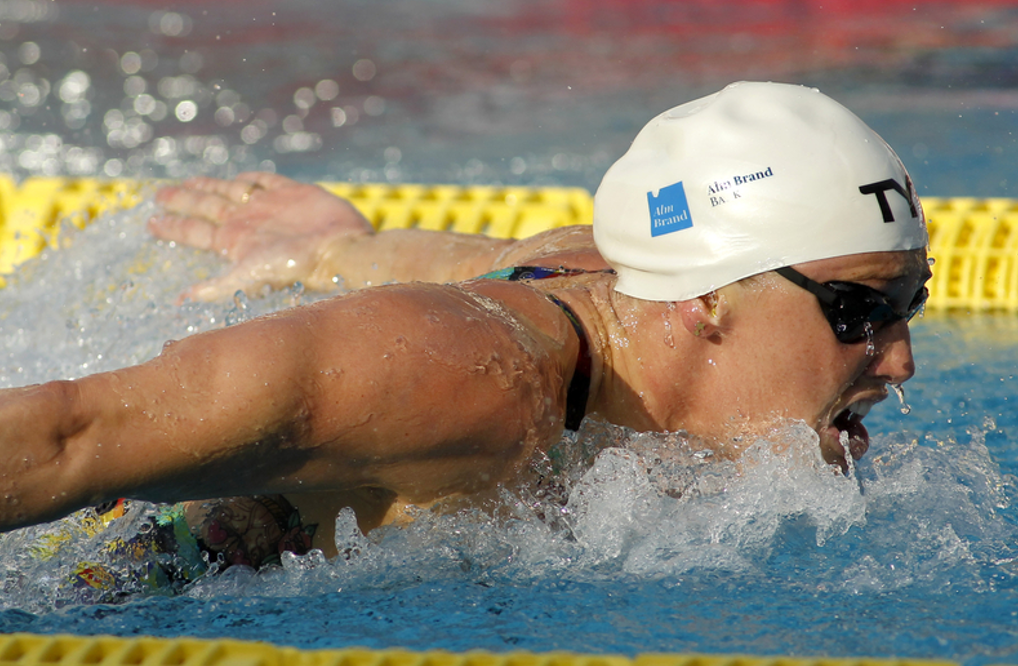

Broken down into basic terms, swimming can be divided into four key phases. Those phases are the start, the free swim (i.e., when the feet are not in contact with the blocks or the wall), turns, and the finish. The responsibility of the strength and conditioning coach is to provide a program that optimally assists performance in each of those four areas. The purpose of this article is to provide information to the strength and conditioning coach to help them accomplish that goal.

Benefits of Strength Training for Swim Performance

It is important to acknowledge that swimming is unique compared to other sports in that participants compete while partially submerged in water. Further, swimming also differs from other sports in other ways. For example, swimmers are in a prone, horizontal position; both arms and legs are used to propel through the water; being submerged results in pressure on the body affecting breathing; other than during starts and turns, while away from the blocks and the wall forces generated from the athlete are only applied to a moving element (i.e., water).

Older studies often discounted traditional strength training as a way to enhance swimming performance. Typically, swim coaches predominantly prescribe high-volume work in the pool, usually neglecting the role of strength training altogether. It was common for swimming coaches to advise against lifting weights, with the belief that strength training would have the effect of making you bulkier and thus less buoyant. However, that idea is incorrect according to newer research. Muscle mass drives strength, and greater muscular strength allows you to produce more force to propel yourself forward faster.

Swim performance continues to improve with the inclusion of strength training as a part of the overall program. The improvements in swimming performance are primarily related to training methodologies where the emphasis has shifted from purely in-water high-volume training to a more balanced approach that includes dry land training in the strength and conditioning facility. Studies have shown that strength training improves muscle power, stroke efficiency, and overall swimming speed. It is now well accepted that swim performance can be improved not only as a result of training in the pool but also with dry land training in the weight room. At this point, it is widely accepted that developing muscular strength and power are critical in elite swimming performances, and it is widely accepted by coaches and athletes that strength training is an important part of preparing for competition.

How Strength Training Improves Swimming Efficiency

How does strength training improve swim performance? The primary benefit of strength training is an increase in muscular strength, and strong, explosive muscles are more effective at pushing the water behind you. Swimmers need great mechanical power output and muscular strength to enhance the ability to apply force in the water, and upper body strength is essential in swimming to generate propulsive forces and increase swimming velocity. Further, an increase in strength reduces fatigue, which assists in maintaining better technique, body alignment, and balance in the pool, making each stroke more efficient.

While the ideal design of a strength training program designed for swimmers has yet to be identified, it is clear, based on research, that a combined program of swimming and resistance training is superior to a swim-only approach to training. As a result, swimmers today know that training for superior performance in the pool involves more than enhancing stroke technique and increasing cardiovascular endurance. Strength training is also required when it comes to improving performance in the water. Swimming is a whole-body activity that requires simultaneous coordination of the upper and lower limbs for best performance in the water. As a result, developing the necessary musculature support platform is essential for swimmers.

Specificity of Training in Swimming

One question that has yet to be answered when designing a training program for swimmers is whether the transfer of strength training follows the specificity of training principle, which is a tenet in the training programs of most athletes. There is disagreement in the literature as to which training methods contribute most effectively to performance improvements in the pool and to what degree resistance training must be specific to swimming to be beneficial to swimming performance. For example, typical strength training programs for swimming focus on, among other things, traditional strength training exercises along with plyometric training and core exercises, both of which will be discussed further in the article. Generally, little thought is given to selecting resistance training exercises based on movement specificity.

In contrast, in sports other than swimming, most strength and conditioning coaches adhere to the belief that exercise selection should be based on selecting strength training movements that closely match movements found in the sport itself. For example, most strength training programs for football athletes include exercises such as cleans, squats, and bench press because the movements involved in performing these exercises are similar to movements that occur in the sport itself (e.g., blocking and tackling).

However, as previously mentioned, swimming differs from other sports in that the sport occurs in water, and moving through water differs significantly from moving through air because of the far greater density water provides. Further, swimming involves movements (e.g., specifically butterfly, breaststroke, and backstroke) that are hard to replicate in the strength training facility efficiently. As a result, designing a strength training program involving movement-specific exercises for the swimmer becomes much more problematic. The one exception to this, as will be discussed in greater detail later in the article, is in the starts and turns that occur as a part of competitive swimming.

Despite this uncertainty in the optimal design of a strength training program for swimmers, there is widespread support that increasing strength does have a positive effect on improving performance in the pool. It has been found that the inclusion of a strength training program for swimmers, which includes both specific core exercises and plyometric training, can increase both fitness and performance while increasing movement efficiency in the pool. It is thought that coaches should design their training programs to include both time in the pool and in the weight room, and that the volume of training in both areas has to be moderated to avoid overtraining.

Achieving the optimal volume of swimming and strength training requires careful planning and monitoring, with the goal being to prevent both undertraining and overtraining while achieving an optimal balance between training and recovery to maximize performance. At this point, the optimal strength training program to elicit the biggest improvements in swimming performance is still undetermined, and because what works best for one person may not work best for another individual, the idea of a “best” strength training program may be unachievable in a team setting. A study found that low, medium, and high training loads were all effective at improving swim performance in male swimmers. This study found that each training group (i.e., low, medium, and high intensity) demonstrated significant improvements in both strength levels and swim performance.

Strength Training for Starts and Turns

One area where strength training for swimmers is similar to other sports is training for improved performance during the start and turns during a race. It is in these brief instances during a race where training the swimmer becomes similar to training ground-based athletes because the athlete can push off a stable surface (i.e., the starting blocks and wall). While strength training is of value to the swimmer, it is important to realize that training must occur at a resistance level high enough to recruit higher threshold motor units associated with the type II muscle fibers. To assist in training at intensity levels high enough to recruit type II muscle fibers, it is suggested to perform four to five sets of one to six repetitions to improve swim turn performance.

To meet the power required in swimming turns, the strength training programs should be focused on the development of neuromuscular factors. Higher generation of force and velocity in the weight room are related to better start and turn performance because coming off the blocks and the wall are both high-velocity, explosive movements. Because of this, cleans, jerks, and snatches are appropriate exercises to include in a strength training program for swimmers after a strength base has been developed.

Although the time spent on the blocks or wall during even the shortest races is just a fraction of the total race time, performance in these two areas is critical. Powerful starts and fast turns play a big role in decreasing swim times. Indeed, the strength and conditioning coach is most likely to make their greatest contribution in the performance of a swimmer by positively influencing those brief instances the swimmer has access to ground reaction forces, the start, and the turn.

To reduce contact time with the starting blocks and the wall, strength coaches must prescribe exercises that require rapid leg extension, focusing on moving the training load as rapidly as possible. Turning times off the wall are best improved by maximizing peak forces applied to the wall, which reduces wall contact time.

As a result, it can be suggested that explosive lower-body exercises, including split squats and resisted jumps, both of which are beneficial for improving leg drive and thus valuable for improving performance in starts and turns, should be a part of the strength training programs of competitive swimmers. Plyometric exercises, such as box jumps, also help swimmers develop explosive leg power and will be discussed further in the article.

Injury Reduction and Strength Training

First, let me explain the terminology I chose here: injury reduction rather than injury prevention. No training program, no matter how well designed, organized, and supervised, can prevent all injuries from occurring. In reality, the goal is to reduce injuries as much as possible; injury prevention is an impossible goal. One can strive for injury prevention. Still, in reality, the best one can hope for when dealing with high-level competitive athletes, in any sport, is to reduce the opportunity for injury as much as possible.

Initially, you might think of swimming as a sport that would be free from injuries. After all, swimming is a non-contact sport performed in the safe environment that a pool provides. However, this is not the case. Swimming is a repetitive activity, and the repeated movements in swimming can lead to overuse injuries. Injuries can occur in the shoulders, knees, and lower back, and the most common injury site is the shoulders, with some studies suggesting up to 91% of competitive swimmers have had some form of shoulder injury. Continuous swimming results in accumulated fatigue in the shoulders, which can have the effect of reducing both range of motion and stroke length in the involved shoulders, which is obviously something that the swimmer wants to avoid.

While the shoulder is the most common injury site in swimming, it is not the only area where swimmers can be susceptible to injury. For example, hip adductor injuries are more commonly experienced by breaststroke competitors. The combination of high angular velocities and excessive tibial external rotation relative to the femur is a significant contributor to injuries found in both hip adduction and the knee joint, where patella femoral osteoarthritis was a common byproduct of the breaststroke kick.

Another aspect not often considered is that swimming is a low-impact sport where the body weight is supported by the water. Because of this, swimmers can experience less than optimal development of bone mass, which can increase the risk of bone fracture. In contrast to this, strength training can increase bone mass growth, so strength training in the programs of swimmers provides an additional advantage.

In terms of helping to prevent shoulder injuries, applying strength training for the shoulders, back, and rotator cuff muscles provides joint stability and can help prevent shoulder impingement injuries in swimmers. Training the shoulders can help prevent injury, which is always preferred over treating an existing injury. Strength training programs that emphasize shoulder stabilization have been shown to reduce injury rates, especially important in swimmers who are susceptible to overuse injuries because of the repetitive nature of their sport.

Youth Swimmers and Strength Training

Adolescent swimmers can also benefit from strength training. Youth resistance training programs should differentiate from programs meant for older swimmers. To achieve the best results in adolescent swimmers, a training program that combines low-intensity and high-speed movements is recommended. However, there are some inconsistent recommendations in the literature. As a result, practitioners should apply this recommendation with caution.

The primary concern with resistance training in adolescents is the risk of injury resulting from excessive use of soft tissues, especially in the lower back and shoulders. If a resistance training program exceeds a child's capacity, training enjoyment can diminish as a result of acute or overtraining injuries. Adolescents are not little adults, and the programs provided to them need to be adjusted to reduce both the volume and the intensity.

Strength Training Program Design for Swimmers

High-level athletes, in any sport, including swimmers, can generally tolerate a high training volume without the risk of overtraining. This may be especially true for swimmers because swimming is a non-impact sport that doesn’t stress the muscles and nervous system like many other sports. However, swimmers do spend a significant amount of time and energy training in the pool and have to balance dryland training with swimming to avoid overtraining.

There does not seem to be much consensus in designing strength training programs for swimmers. Opinions differ in terms of exercise selection, areas of emphasis (i.e., upper body versus lower body), frequency of training, and so on. However, as is often the case, strength training programs that differ greatly can still produce significant improvements in athletic performance.

For example, hypertrophy training, which typically involves sets of 8 to 12 repetitions or more and rest periods of no more than 90 seconds, and strength training, which usually calls for sets of 2 to 6 repetitions with rest periods of 120 seconds or more, have both shown significant improvement in swim performance. For example, a hypertrophy training program involving 3 to 5 sets of 6 to 15 repetitions was compared to a strength-focused program, and the strength-based program produced slightly better results. It was suggested that a hypertrophy-based program can only be used successfully in subjects without a great deal of experience with strength training.

Another suggestion was a training program using intensities at or above 80% of 1RM with repetitions in the 1-6 range for 3-5 sets. Swimming as a sport is dependent on power and strength because strength training can increase the rate of force development and maximal force. Gains in maximal force are primarily related to increases in hypertrophy, and explosive maximal force production is influenced by neural activation. This is an important component of the arm movement that occurs in the sprint events.

Strength training programs with a lower number of sets and repetitions combined with high velocity and force (i.e., intentionally moving the resistance as quickly as possible) result in superior strength and neuromuscular improvements as compared to high volume and low intensity programs. There is agreement that focusing on lifting speed is a crucial way to enhance swimming performance. Training at high intensities between 85% and 100% RM has a positive effect on the force and power produced during wall contact during a turn and reduces the time on the wall significantly. In contrast, when intensity was lowered to 80–90% of 1 RM, the improvement in time on the wall decreased only slightly. As a result, training at near maximal loads seems to be the most effective training method for improving swimming turn performance.

Upper vs. Lower Body Strength in Swimming

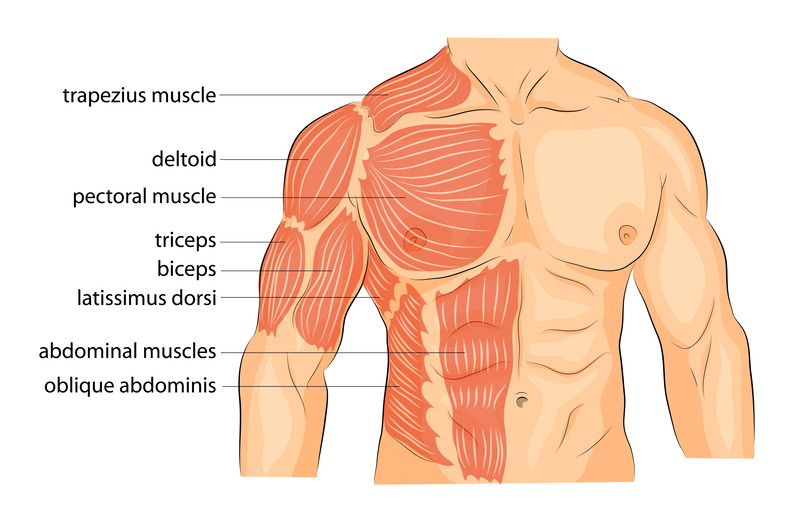

The lack of a consensus on the ideal approach regarding strength training for swimming becomes obvious when some authors suggest the need for “maximal” strength gains in both the upper and lower body. At the same time, others emphasize the importance of only upper body strength, with some suggesting that swimmers must have “extreme” upper body power and endurance to push themselves through the water, specifically emphasizing strength in the latissimus dorsi to create the ability to propel the swimmer through the water. One suggestion involved an upper body program including triceps dips, pushups, lateral raises, biceps curls, bench press, chest flies, and dumbbell rows with no mention of any lower body work at all.

Elite strength and conditioning coaches have emphasized the bench press as an essential exercise to improve both upper-body strength and swimming performance. The primary muscles recruited during the bench press (i.e., pectoralis major, triceps brachii, and deltoid) are also heavily involved in free-style swimming. As a result, performing the bench press can enhance the muscular propulsive forces during free-style swimming and thus obviously improve swim performance.

On the other hand, multiple authors highlighted the need for lower-body strength in swimmers. Several authors have emphasized the need for lower body strength and power for swimmers, with studies showing the correlation of lower body strength and times in 25- and 50-meter distances. One repetition maximum in the back squat has been shown to be significantly related to time over 15 meters, along with both peak vertical and horizontal forces, both of which are obviously significant to performance from both the starting blocks and off the wall.

Strengthening the lower body occurs much more effectively in the weight room than it does in the pool, and a strong lower body is important for injury prevention. A program consisting of squats, lunges, side lunges, reverse lunges, wall sits, calf raises, glute bridges, leg curls, and leg abduction performed in a circuit fashion was suggested.

Adapting Strength Programs by Stroke and Distance

According to the need for specificity of training, race distances are essential because the physiological demands of sprint events differ greatly from endurance races. For example, endurance events require greater aerobic capacity, muscular endurance, and efficient energy utilization than do shorter events. Accomplishing those adaptations requires an emphasis on lower intensity, higher repetition training in the strength program, along with sustained core stability work to support extended performances in the pool. In contrast, sprint events are largely dependent on anaerobic power, explosive strength, and fast-twitch fibers, and those fiber types are best trained using high-intensity resistance training and plyometrics.

Further, strength requirements vary depending on the stroke type(s) the swimmer competes in. For example, butterfly and breaststroke swimmers frequently need increased focus on shoulder stability and hip mobility because of the greater range of motion and rotational forces involved in those strokes. In contrast, freestyle and backstroke swimmers may be best served by emphasizing core strength and streamline body positioning to reduce drag and improve stroke efficiency. Designing strength training programs to match the distances swam and the stroke used enhances the swimmer’s strength and endurance and also helps reduce specific injuries, contributing to a more effective and individualized training program.

One of the primary variables that needs to be determined when designing a strength training program is the frequency at which training will occur. The optimal strength training frequency for swimmers depends on several factors, including experience, training goals, age, and the time within the competitive season. Interestingly, the strength training frequency for elite swimmers is not significantly different from that of lower-level swimmers, generally ranging between two and four times per week based on the training age of the athletes and the current phase of training.

It is important for elite-level swimmers to follow an individually designed program to maximize strength and power while decreasing negative interference with the prescribed swim training volume and intensity. In general, at least two strength sessions will be necessary for ideal gains from the strength training program. However, more than four days per week will likely offer few, if any, additional benefits and might actually have a negative effect on swimmers because of the combined fatigue from lifting and swimming.

In terms of sequencing swimming and lifting sessions during the week, remember that adequate rest time is required to recover from strength training and challenging swim sessions. Heavy lifting days should not occur on the same day as high-intensity swim practices or competitions. If both lifting and swimming must occur on the same day, strength sessions should occur on lighter swimming days or after swim practice to avoid negatively affecting swim performance. At least one day of rest or an active recovery day should occur each week to allow the body to recover.

During the peaking process for a competition, lifting should either be eliminated or the programming adjusted to focus strictly on power and mobility once or twice per week. Exercises such as box jumps or medicine ball throws can be performed, but exercises such as heavy deadlifts or bench press should be eliminated to allow the body to recover, recuperate, and prepare for competition.

Core Training for Swimming Performance

The importance of core training is recognized as a critical component in the training programs of all types of sports, not just swimming. Core training can be defined as an organized group of exercises that focus on the muscles making up the core of the body. Those muscles include:

a. Transverse abdominis

b. External obliques

c. Internal abdominal obliques

d. Diaphragm

e. Latissimus dorsi

f. Gluteus maximus

g. Trapezius

While training, the core is important for all athletes; it becomes especially important for swimmers because core stability is required due to the unstable nature of water. Notably, core training has been shown to result in significant improvements in both swimmers’ core function and performance in the pool.

Regarding strength training focused on the core musculature, resistance training programs that focused on core strengthening exercises were more effective at improving swim performance than programs that involved only traditional swim training. While both programs improved swim performance, the core training group demonstrated superior performance improvement. It was suggested that the superior improvements in performance by the core training group were the result of the core training improving the stability of the lower and upper limbs, which allowed the energy to be transferred more efficiently.

Focusing on increasing strength in the core muscles is beneficial because of the instability that occurs while submerged in water. Further, stability in the core is required to produce and then transfer force through the trunk to the upper and lower extremities of the body. Swimming is unique from ground-based sports in that the core becomes the reference point for all movements. That is, other than while in the starting blocks or against the wall, your feet are not on a stable surface. As a result, the core muscles become the central anchor, and all limb movements originate or are stabilized by the core. Explained another way, in swimming, the core becomes the body’s foundation from which force is generated, coordinated, and transferred.

Further, core stability and mobility are required for proper stroke mechanics and propulsion and are acknowledged as being necessary for optimal performance at all competition levels. Including core training in the dry land training has been shown to improve swim performance and postural control. This has the effect of improving proprioception and reducing the opportunity for injury.

In addition, the ability to create the ideal body position during both the approach to and separation from the wall in the desired streamlined glide position requires a high level of core strength. When executing a turn, the core muscles help maintain the desired streamlined position. By maintaining a straight-line position during turn phases, the swimmer can reduce drag and improve velocity.

A strong and stable core also helps to achieve both proper swimming technique and improves swimming endurance. Core circuits will include exercises like crunches, planks, sit-ups, leg lifts, twisting crunch, side plank, glute pushups, and V-sit holds. It was suggested that the movements be performed in a circuit, moving from exercise to exercise, completing two sets with a 60-second break between rounds, three days per week.

Plyometric Training for Swimmers

Plyometric training has gained a lot of attention regarding training the swim athlete. Plyometric training is a technique used to enhance explosive strength. The improvement in explosive strength comes from optimizing the stretch-shortening cycle. The stretch-shortening cycle occurs when the active muscle switches from rapid eccentric muscle action (deceleration) to rapid concentric muscle action (acceleration). Think of dropping from a box and landing (the deceleration phase) and then immediately exploding out of that landing phase (the acceleration phase) into a jumping action. This rapid switch from deceleration to acceleration has the effect of improving muscle function, coordination, and the direction of the resultant force.

This action used in plyometric training is in line with the desirable swimming turn characteristics. That is, a fast stretch shortening cycle occurs when the muscles switch from a rapid eccentric muscle action (contact and approach to the wall) to concentric muscle action (separation from the wall). Because of this, plyometric training has been used in swimming as a training method to increase the power output and force production on swimming turns.

As a result, to reduce contact with the pool blocks and wall during starts and turns, plyometric training that improves rapid leg extension should be prescribed. Indeed, plyometric training has been suggested to be one of the most relevant training methods in swimming because it results in the enhancement of muscle strength and power due to neural improvements.

Plyometric training has several advantages relative to other strength and conditioning training methods. These advantages include ease of integrating plyometric training into the normal training sessions of the swimmers and the limited financial cost because plyometric training does not require any expensive equipment. However, for the best results, plyometric training should be combined with strength training rather than used as a stand-alone activity.

To assess the value of plyometric training, a study was conducted evaluating the benefits of plyometric training on start performance out of the blocks. The study consisted of hour-long sessions using a variety of low-intensity plyometrics and progressing to more advanced drills over time. Eight weeks of plyometric training provided a mean reduction of 0.59 seconds in start time, resulting in significant improvement in start performance. In addition to leaving the blocks faster, the swimmers also increased the distance covered from the blocks.

Using a movement such as a split broad jump or a split squat jump, which works on improving both horizontal and vertical power, has been suggested as an appropriate movement to improve the split stance used to start off the blocks. However, the countermovement used when executing the turn suggests that plyometric exercises, such as counter movement jumps and drop jumps, may be an appropriate training method for this portion of the race.

After the start, the turn is the other point during a race where the athlete is able to utilize ground reaction forces. A study found that the time spent on the wall for swimmers during the turn was between 0.3 and 0.5 seconds, which accounted for just 1.5% of the total race time in a 50m event. The positions used by the swimmers during the turn to apply ground reaction forces are similar to those used when performing a counter movement jump. It can be assumed that, like improvements in the start, improvements can also be made in turn performance with the use of plyometric training.

Battle Ropes for Sport-Specific Conditioning

A variety of strength training methods, such as barbells, dumbbells, and exercise machines, are commonly used in the strength training programs of swimmers. Less common, but also used, are such things as resistance bands and medicine balls. Also uncommon, but gaining in popularity in the training programs of swimmers, are battle ropes, and they deserve mention here.

For those who are unfamiliar, battle ropes are typically ropes that are 1.5” to 2” inches in diameter and 25’ to 100’ in length and weigh 50 to 75 pounds. The history of using battling ropes as a training method can be traced back to ancient Greece, where ropes were used as a training method for wrestlers and other athletes. Battle ropes have been made popular in the current programs of athletes by John Brookfield, a well-known strength and conditioning coach.

It is suggested to start with lighter-weight ropes and gradually increase both the weight of the rope and the duration the exercises are performed over time. Battle ropes can be swung in an undulating manner up and down, side to side, or in any manner of creative patterns. The continuous muscle tension challenges both muscular strength and endurance. Typically, the closed end of the ropes is tied or connected to a stable object.

Training the body in a sport-specific pattern that mimics the movement pattern that occurs in the water can be difficult in the weight room. Traditional strength training exercises are performed in a standing position, which does not match the needs of the swimming athlete. While battle rope exercises are also most commonly performed in a standing position, the ropes can also be used while in a Roman chair. This places the swimmer in a sport-specific position while the arms and shoulders are recruited to swing the rope in the required movement pattern. In this position, the core must stabilize the body to allow the ropes to be swung in the desired movement pattern. The more aggressively the ropes are swung, the more challenging the exercise becomes. Further, the ropes are inherently unstable, which causes the stabilizer muscles to maintain the correct movement pattern. Because battle rope training is unique, a partial list of battle rope exercises that can be performed is provided below:

A. Slam – This is a wavelike motion of the body and arms with power coming from the glutes. Start down and move your body and arms upward and downward quickly in one powerful motion to slam the rope on the ground.

B. Dual Wave – This move involves keeping the body straight with the head down and the arms out straight. Make alternating waves by moving your arms in an alternating pattern.

C. Rotating Slam – This movement is similar to the slam, where the body moves in a wavelike motion; however, on the way up, the arms start side by side and then go up and out in large circles.

D. Horizontal Wave – This move is similar to the dual wave because the body is straight with arms out in front and head down; however, the arms move laterally, making alternating flat waves.

The advantage of battle rope training, especially when performed on a Roman chair, is that it allows a more sport-specific method of training for swimming athletes. Further, these battle rope movements transfer effectively to freestyle swim techniques and can assist in muscular endurance.

Conclusion

Strength training has become an important aspect of the training program for competitive swimmers. Resistance training is widely accepted for the role it plays in improving strength, power, and stroke efficiency. Evidence supports including strength training because of its role in key race phases (i.e., starts, turns, free swim, and finishes). This is because of the role strength training plays in generating greater propulsive force and reducing drag, as it has the effect of improving both body positioning and core stability.

While there is no single widely accepted model for designing the optimal strength training program for swimmers, evidence suggests that a well-structured strength training program, including maximal strength and power-focused procedures, contributes significantly to swim performance. Further, specific training methods, including plyometric training, core exercises, and battle rope activities, can offer further benefits when properly integrated into the training plan.

It is important to note that strength training, while improving performance, can also reduce injury rates, especially in the shoulders. Special considerations must be given to adolescent swimmers and providing them programs designed specifically for that age group, and not simply providing them a workout meant for an adult athlete. Resistance training programs for youth swimmers is a good approach for improving both athletic performance and long-term athlete development.

References

1. Abelsson, A. Strength training for swimmers: benefits & training program. Strengthlog.com. 2024. Retrieved April 2024 from https://www.strengthlog.com/strength-training-for-swimmers/.

2. Amara, S., Crowley, E., Sammoud, S., Negra, Y., Hammami, R., Chortane, O.G., Khalifa, R., Chortane, S.G., and van den Tillaar, R. What Is the optimal strength training load to improve swimming performance? A randomized trial of male competitive swimmers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(22), 2021.

3. Amaro, N.M., Morouço, P.G., Marques, M.C, Batalha, N., Neiva, H., and Marinho, D.A. A systematic review of dry-land strength and conditioning training on swimming performance. Sports & Science 34(1), 2019.

4. Ball, S. Build Your Swimming Power and Endurance with the Roman Ropes Workout. Stack.com. 2013. Retrieved April 2025 from https://www.stack.com/a/roman-ropes-workout/.

5. Bishop, C., Cree, J., Read, P., Chavda, S., Edwards, M., and Turner, A. Strength and conditioning for sprint swimming. Strength and Conditioning Journal 35(6):1-6, 2013.

6. Carpenter, A.J. Circuit Training for Swimming. SportsRec.com. 2011. Retrieved April 2025 from https://www.sportsrec.com/350670-circuit-training-for-swimming.html.

7. Crowley, E., Harrison, A.J., and Lyons, M. The impact of resistance training on swimming performance: a systematic review. Sports Medicine 47(11):2285-2307, 2017.

8. Fields, B. and Hartman, J. Swimming Performance. NSCA Coach 10(3): 2023.

9. Fone, L., and van den Tillaar, R. Effect of different types of strength training on swimming performance in competitive swimmers: a systematic review. Sports Medicine 8(19):2022.

10. Get Physical.Com. Battling Ropes: A Complete Guide to History, Exercises, Benefits, and Science. Get Physical.Com. Retrieved April 20025 from https://www.getphysical.com/blog/Battling%20Ropes.

12. Guo, W., S, Soh, K.G., Zakaria, N.S., Taufik, M., Baharuldin, H., and Gao, Y. Effect of resistance training methods and intensity on the adolescent swimmer's performance: a systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health 10, 2022.

12. Hermosilla, F., Sanders, R., González-Mohíno, F., Yustres, I., and González-Rave, J. Effects of dry-land training programs on swimming turn performance: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(17) article number 9340, 2021.

13. Judge, L.W. and Biddle, A. Beyond the pool – improving swimming performance with dryland training. NSCA Coach 12(1):22-29, 2025.

14. KarpiÅski , J., Rejdych, W., Brzozowska, D., GoÅaÅ, A., Sadowski, W., Swinarew, A.S., Stachura, A., Gupta, S., and Stanula, A. The effects of a 6-week core exercise program on the swimming performance of national-level swimmers. Plos One 16(8) 2020.

15. Muniz-Pardos B., Gomez-Bruton, A., Matute-Llorente, A., Alex Gonzalez-Aguero, A., Alba Gomez-Cabello, A., Gonzalo-Skok, O., Casajus, J.A., and German Vicente-Rodriguez, G. Swim specific resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 33(10):2875-2881, 2019.

16. Myers, C. Dryside Training for swimmers, using ropes to increase muscular endurance. NSCA Coach 4(4): 50-57, 2017.

17. Meyers, C. Dryside Training for Swimmers - Using Ropes to Increase Muscular Endurance. Hunter Allen Power Blog. 2018. Retrieved April 2025 from https://www.hunterallenpowerblog.com/2018/02/dryside-training-for-swimmers-using.html.

18. Next Alpha. Are Battle Ropes Good for Swimmers? Exploring the Benefits. Next Alpha: Functional Fitness Blogs. 2023. Retrieved April 2025 from https://www.nextalpha.eu/blogs/functional-fitness/are-battle-ropes-good-for-swimmers-exploring-the-benefits.

19. Nugent, F.J., Comyns, T.M., and Warrington, G.D. Strength and conditioning considerations for youth swimmers. Strength and Conditioning Journal 40(2):31-39, 2018.

20. Nugent, F., Comyns, T., Kearney, P. and Warrington, G. Ultra-Short Race-Pace Training (USRPT) In Swimming: Current Perspectives. Sports Medicine 10: 133-144, 2019.

21. Price, T., Cimadoro, G., and Legg, H. Physical performance determinants in competitive youth swimmers: a systematic review. MBA Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 16(20):2024.

22. Rodríguez, G., Melguizo-Ibáñez, E., Martín-Moya, R., and González-Valero, G. Study of strength training on swimming performance. A systematic review. Science and Sports 38(3):217-231, 2023.

23. Ruiz-Navarro, J., Santos, C.C., Born, D.P., LópezâBelmonte, O., Fernández, F., Sanders, R.H., and Arellano, R. Factors Relating to Sprint Swimming Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine (55):899–922, 2025.

24. Tillaar, R.V.D. Effect of Different Types of Strength Training on Swimming Performance in Competitive Swimmers: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 8, article number 19, (2022).

25. Tomazin, K., Strojnik, V., Feriche, B., Ramos, Garcia Ramos, A., Štrumbelj, B., and Stirn, I. Neuromuscular Adaptations in Elite Swimmers During Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training at Low and Moderate Altitudes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 36(4):1111-1119, 2022.

26. Uma, M.A., Palanisamy, A., and Antony, B. Effect of battle rope training on selected physical and physiological variables among college-level athletes in physical education. Indian Journal of Applied Research 5(5):19-22, 2015.

27. Verma, S. Effect of strength training exercises for the development of speed among free-style events in swimming. International Journal of Physiology, Nutrition and Physical Education 7(1): 270-272, 2022.

28. Waller, M., Shim, A., and Piper, T. Strength and conditioning off-season programming for high school swimmers. Strength and Conditioning Journal 41(5): 79-85, 2019/

29. Wirth, K., Keiner, M., Fuhrmann, S., Nimmerichter, A., and Haff, G.G. Strength training in swimming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(53690):1-32, 2022.