Basketball, Soccer, Strength And Conditioning, Volleyball

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

How Can Athletes Maintain Healthy Knees?

One of the most common injuries in sports is to the knee.

Often, athletes will say they have "weak" knees and will end up getting a brace, neoprene sleeve, or tap to help them perform better. Does it help? Not really. What we need to get to is the "root cause" and address that.

Most common knee injuries in athletes

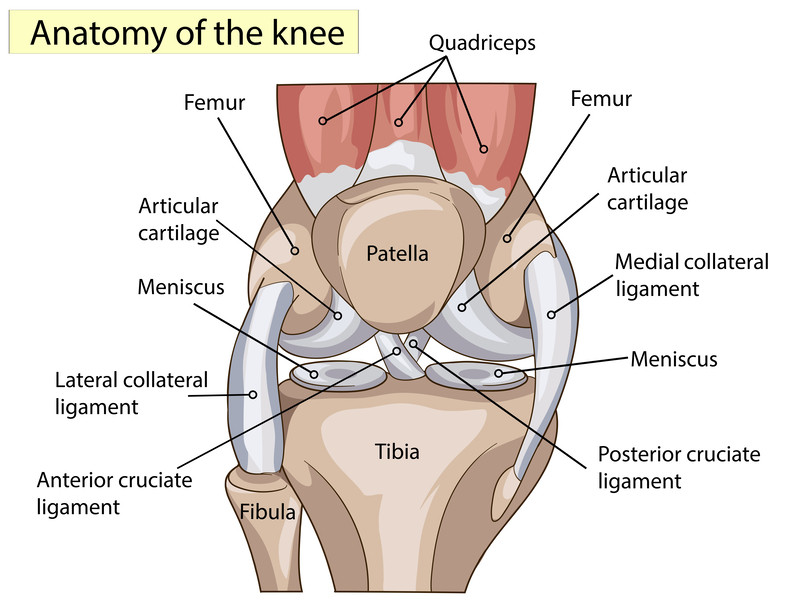

Some of the most common knee injuries in athletes include patellofemoral syndrome, IT band friction syndrome, meniscal tears, and ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injuries. Often, we wonder how we can keep doing the sport we love while maintaining healthy, non-painful knees. What if I told you it is possible but does require you to be persistent?

With sports, especially running and jumping sports (volleyball, soccer, basketball, football, lacrosse, etc.) there is a tremendous amount of force that is absorbed in the lower limb (from the foot to the low back). These forces can range, depending on the surface, anywhere from 4 to 8 times body weight.

As such, if the body is not moving optimally, then these forces can be increased, and forces and stresses to the tissues of the knee can exceed their tolerance level, resulting in injury. One thing that can increase stress on the knee is if there is a limited range of motion in the joints distal (below) or proximal to the knee.

When a joint has a proper range of motion, then this allows the muscles surrounding that joint to lengthen during movement. The elasticity and strength of those muscles allow them to eccentrically lengthen and in doing such absorb force.

So, if there is a limited range of motion of the ankle due to tightness in the gastrocnemius, then the joint does not go through its full range of motion and the force that is typically absorbed in the foot and ankle has to be absorbed in the next joint up the system, the knee. This means the force that the knee typically absorbs is now 2-3 times greater.

Poor strength can also lead to an increase in force that has to be absorbed in the knee. As alluded to above, as the joint goes through a range of motion, then the muscle is lengthened. The muscle resists this motion and, in doing so, will absorb force.

If the muscles of the foot and ankle are weak, for example, then as the foot starts to absorb force, the arch collapses. It is the intrinsic muscles of the bottom of the foot that provide support for the arch and allow the arch to expand, contract, and absorb force. If these are weak, then as the force is being absorbed, the arch collapses, and the force is transferred to the next joint in the system (the knee). Much like a shock absorber in your car, if the shock absorber completely collapses under the force of the bump the car hits, you feel the jolting force on the inside of the car since it was not able to absorb that force.

Another way weakness can add to increased stress on the knee is if the muscles of the hip are weak. If the hip muscles are weak (specifically the gluteus medius), this will allow the limb to go through excessive motions. As the limb absorbs force, the knee will have excessive valgus (fall in towards midline), and the foot will excessively pronate (arch collapse).

When this happens, the structures of the knee and ankle are placed under a lot of stress. The more weakness there is, the faster the limb will fall into these motions. For example, mild weakness may result in the knee falling into valgus at 20 degrees per second.

Significant weakness may result in the limb falling into the valgus at 150 degrees per second. The faster the limb falls into the valgus, the more force is imparted to the knee joint and the more likely it is to be injured.

In 2017, we developed a technology (wearable sensor) that is used to measure these motions with lab-quality data. Since that time, we have collected data on >40,000 professional, college, and high school athletes leading to >60M data points related to human movement. As such, this has taught us a lot about barriers to how much the limb should move during certain tasks and what some normative values are for those motions and speeds.

For example, when performing a single leg hop, if your knee falls into greater than 10 degrees of valgus at greater than 100 degrees/sec, this puts you outside the normative values. What does that mean? Simply that there is an increased likelihood that these movements will negatively impact how your limb absorbs force and have a negative impact on athletic performance.

Next blog, we will discuss what movements we look at and how we look at them, so stay tuned.

Read more: