Health

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

The Dreaded ACL Injury – Is There a Solution? Part V

In the last article, we talked about the squatting motion and how some of the deficits that we note in this motion could add to weakness and some of the pathological movements we see that put our athletes at risk for injury.

This despite the fact that these movement patterns may have existed for years and been reinforced as a part of their strength training program does not mean that it cannot be corrected or not a problem.

Some authors will tell you to stop the athlete from doing squats until this motion can be corrected. Frankly, I feel this is the worst thing you can do. One reason is that athletes and coaches who feel squats are a fundamental part of their training are much less likely to do or be compliant with your recommendations if you start out with this.

Secondly, you don’t need to do that to correct it. If you recall from the previous blog, I mentioned that these motions that we see in non-weighted conditions tend to get worse in weighted conditions. That said, you can reduce the weight that the athlete does and get to a point where they can perform the squat without the abnormal movement. This will be at a much lighter weight than they are used to using but, this is creating a foundation from which they will build on.

What we see is that athletes who correct this motion will increase their weight and many times PR above their previous PR. This makes sense because now that they are actively engaging the opposite side to the same degree and you are able to progress further than previous.

Believe it or not, there is a big controversy on whether or not fatigue increases your risk of ACL injury. Personally, I think we just have not figured out yet to accurately assess this in the research. There are studies that show that an increase in fatigue does add to an increase in frontal plane motion at the knee (Brazen et al Clic J Sport Med 2010) and that an increase in fatigue results in an increase in dynamic valgus at the knee and an increase in ground reaction forces at the knee (Nessler et al Cur Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017). We also know that fatigue leads to a decrease in maximal volitional contraction of the gluteus medius which leads to an increase in frontal plane motion (Weist et al Am J Sport Med 2004).

These are all things that lead to an increased risk of injury. However, you don’t need to be a scientist or researcher to know this. As a coach, we see all the time. When our athlete’s get tired on the field their movement becomes less efficient and performance faulters. When a wrestler gets tired and they go to shoot in, this is less explosive and we see more dynamic valgus on their plant leg. I firmly believe, we have not figured out how to assess fatigue accurately in the research.

If you look at the studies being done to assess fatigue state in an athlete, most are using different protocols. There is no consistency in the protocols used to assess fatigue in an athlete. However, there is ONE protocol that has been shown to impact lower limb biomechanics in athletes (Quamman et al J Athl Train 2012) and it is called the FAST-FP (Functional Agility Short Term Fatigue Protocol). The FAST-FP is a great protocol that coaches can use to see the impact that fatigue and poor biomechanics will have on their athletes. This 4 ½ minute protocol that takes the athlete through a multidirectional (varying directions) as a part of the protocol. Considering, you will very accurately see where their flaws are in their movement and this can give us some further indication of some kinds of training we can do (which we will talk about in the next blog).

|

| The FAST-FP protocol has 4 exercises that are performed. |

- Starts with a 31cm step up for 30 seconds to the beat of a metronome at 220 bts/min.

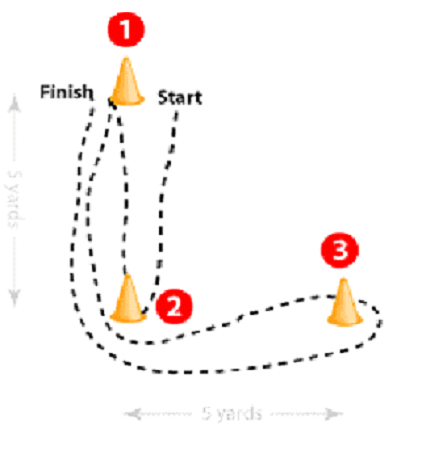

- 5-yard L-drill (depicted here)

- 5 vertical jumps at 80% max

- 5-yard agility latter (1st set and 3rd set done forward with high knees, 2nd and 4th set done sideways with high knees)

This is repeated four times without any rest. This is a great protocol for coaches who want to truly see how poor movement is impacting their athletes. For our high-level athletes (DI soccer and MMA athletes) we will run them through this prior to our movement assessment. In our higher end athletes, this will often lead to us identifying 30-40% more folks that we should include as a part of our program. Folks who’s movement changes so much that there an increased risk of injury and which we also know will negatively impact their performance.

For coaches, this is simple and quick protocol you can implement to see the direct impact on your athlete. The key to this test is to make sure you are pushing them through. Don’t let them do it with 50% effort. I push all my athletes going through this to give me maximal effort the whole way through. That said, you should exercise caution on the step up. On the third and fourth time through, the athlete is extremely tired. It is not uncommon for the athlete to trip attempting to do the step at this point. I will typically slow them down a little on this part for safety reasons and push them hard through the remainder of the protocol.

Having done this with 1000+ athletes, we have learned a lot. As such, it has been a main driver for implementation of the injury prevention program we used. We will talk about this in detail in the next blog. For anyone interested in the FAST-FP protocol, follow me on Instagram at BJJPT_acl_guy and DM for the protocol. Happy to share.

In our next blog, we conclude this discussion by talking about fatigue state training. What is it and how do we do. I hope you found this information useful and looking forward to sharing more with you.

Read more:

The Dreaded ACL Injury – Is There a Solution?

The Dreaded ACL Injury – Is There a Solution? Part II

The Dreaded ACL Injury – Is There a Solution? Part III

The Dreaded ACL Injury – Is There a Solution? Part IV