Strength And Conditioning, Health

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Shoulder Friendly Weight Lifting Part I

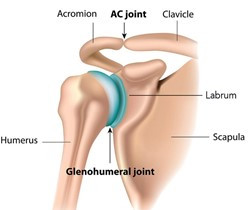

As a physical therapist, one of the most common injuries I see coming out of the gym or weight room with athletes is shoulder injuries. The shoulder (or glenohumeral joint) is an inherently unstable joint which is essential to allow it to have such a large degree of movement. The bones that make up the shoulder include the humerus, scapula, clavicle, and ribs. Movement of the shoulder comes from the humerus moving on the scapula at the glenohumeral joint and the scapula moving on top of the ribs.

Stability of the shoulder is complex and is provided by the muscular that surrounds it, including the rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor), rhomboids, trapezius, biceps, and serratus anterior to name a few. There is also stability provided by the labrum and ligamentous structures (glenohumeral ligament, coracohumeral ligament, etc.) that surround the shoulder. A weight lifting shoulder injury can include any one of these structures.

The four most common injuries I see related to lifting are:

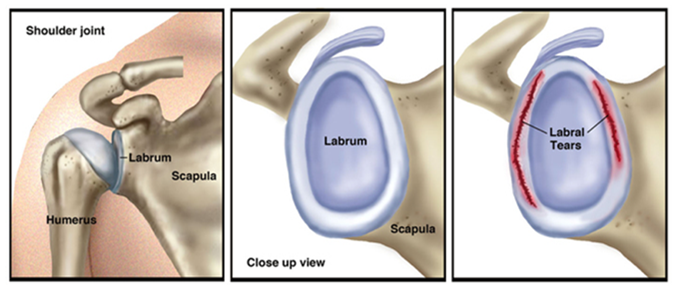

- Labral tears – the labrum is the cartilage between the humeral head and the glenoid fossa of the scapula. This cartilage provides stability to the shoulder and if compromised can add to shoulder pain and instability.

- Rotator cuff tears – of the four rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder, the one that is most commonly injured with lifting is the supraspinatus. This adds to shoulder pain, limited range of motion and if ruptured, can severely limit shoulder function.

- Long head of biceps – the long head of the biceps attaches to the anterior superior (front top) portion of the labrum. This can result in bicep pain, shoulder pain, labral tears or biceps ruptures.

- AC Joint pain and separation – the acromioclavicular (AC) joint is in the front of the shoulder and injury can cause pain, limited shoulder range of motion and inability to put weight on that arm.

All of these are common injuries in the gym and can be avoided by simply knowing how they are injured in the first place and ways to modify your gym routine to protect these structures. Most shoulder injuries occur when the shoulder is put into some compromised position and under heavy loads. It is the compromised position plus the load in that position that ends up, over time, causing a problem. This does not mean stop those exercises, but modifications to them mitigate your risk for a shoulder injury and increase the likelihood you can train throughout your lifetime.

Some of the most common exercises that result in shoulder injuries:

- Chest exercises – bench press, dumbbell flies, pec deck, dumbbell bench/incline

- Back exercises – behind the head lat pulls, rows

- Shoulder exercises – upright rows, behind the head shoulder press, front raises/lateral raises with palms down, shrugs

- Leg exercises – rear squats

With a lot of the chest exercises, these tend to put the shoulder at the end range of motion (stressing the ligamentous structures, cartilage, and cuff muscles) while the pec is elongated maximally (therefore at its weakest). This combo puts even more stress on the structures. This is a bad combo, especially if you have an underlying weakness in the rotator cuff or irritation to the labrum.

With the back exercises and rear squat, it is the behind the head portion that compromises the shoulder. These put the shoulder in a compromised, unstable position and often painful position under load. For rows, when you extend your arm past your trunk (very end range of row), this not only stresses the ligamentous structures but at the same time, requires a lot of bicep contraction which means it is pulling hard on the labrum which is already in a compromised position.

For shoulder exercises, due to the position of the hand, the majority of these exercises pinch the rotator cuff in the subacromial space. With the palms down, many times this mimics a provocative test we use to see if you have a rotator cuff tear. Knowing this, I always tell my weight lifters, if your exercise mimics a test that I do to see if you have an injury, then the exercise will eventually cause an injury.

Next time, we will look at some specific things you can do and add to your routine to mitigate your risk for a shoulder injury with your routine.

Read more:

Shoulder Friendly Weight Lifting Part I