Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Know Squat?

There’s nothing particularly unusual about the act of squatting. Around the globe squatting may be part of one’s daily ritual, be it for elimination purposes, conducting business, or simply watching the world go by. In the United States squatting is mostly associated with some form of physical exercise.

In our world of weightlifting and strength training the ability to comfortably and efficiently squat often fades soon after childhood. This inability to comfortably squat is mostly related to loss of flexibility, particularly dorsiflexion of the ankle joints. Although we may have squatted easily as infants, as soon as we take to sitting in chairs or on sofas we seldom have a reason to again squat. That is until we take up weightlifting.

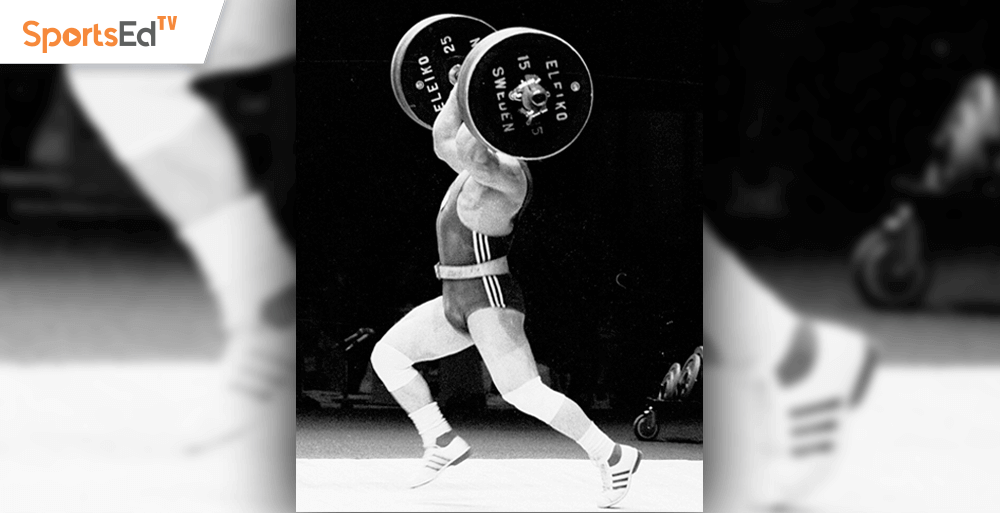

Achieving a proper receiving position for the squat version of the snatch or the clean requires good flexibility in the “bottom position,” ideally with the knees forward of the toes (ankle dorsiflexion). Coaching weightlifters that exhibit a loss of flexibility in this area is a challenge.

What Is a Squat?

Pull up information on squatting (and there is a lot of it) and all too often we are bombarded with the message that one should never allow the knees to move forward of the toes. In other words, keep the ankles neutral (lower leg approximately perpendicular to the ground), and avoid ankle dorsiflexion.

When squatting with proper dorsiflexion the shear forces focus near the knee joints. Keep the shank (lower leg) near perpendicular to the floor, and one must lean forward (or fall backward), thus shifting the shear to the lumbar spine region.

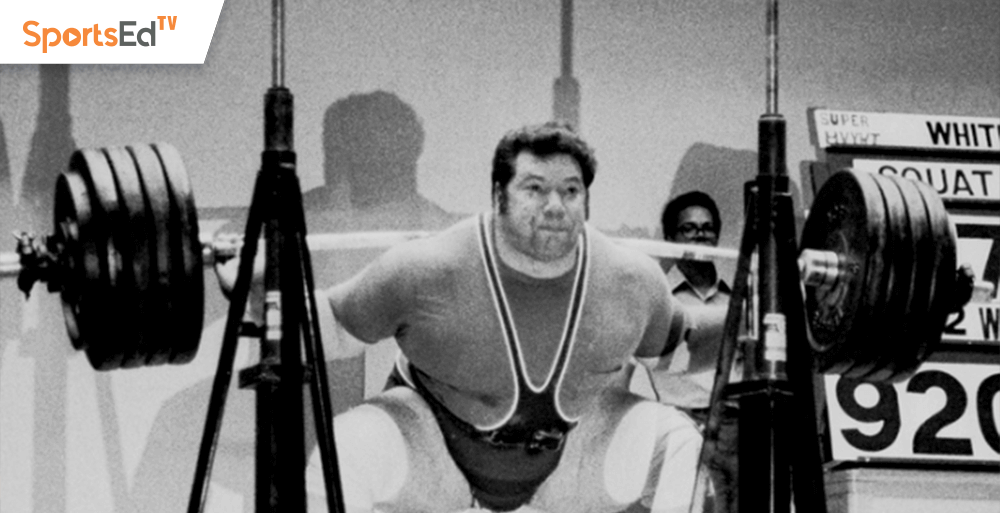

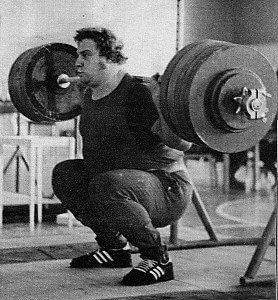

When seen from the side, both powerlifters and weightlifters aim to keep the bar over the middle of the foot. But how they achieve this varies. A powerlifter positions the bar farther down the upper back (“low bar squat”) than a weightlifter (“high bar squat”) and aims to keep the shanks nearly perpendicular while descending to a more shallow depth than the weightlifter. In such a posture the head and torso must project forward, with the hips rearward, behind the heels. This allows powerlifters to maximize loads handled in their competitive lift, the squat.

Compared to powerlifters, weightlifters squat deeper and tend to aim for an upright torso, again, similar to how they catch or rack their primary competition lifts.

A weightlifter in such a powerlifting squat position would have difficulty catching a snatch or racking a clean prior to recovery; it’s advantageous for us to sit upright in the bottom. In order to sit upright with a neutral spine, hips near heels, and no space between the hamstrings and the gastrocnemius, the knees have to move forward of the toes.

Naturally, during recovery, the weightlifter’s hips drift rearward, and the knees and ankles resemble more of the powerlifter’s positions. This change from receiving to recovery position allows a weightlifter to more easily pass through the “sticking point.”

Such competitive style differences, along with inconsistent terminology in the industry, can be confusing. Simply telling someone to squat may lead to confusion. Truly, a squat is not a squat. Think about terms like “full” squats, “parallel” squats, “1/2” squats, box squats, etc. A full squat cannot be simply defined as having the hips below parallel, as lifters with short femur (thigh) bones cannot get below parallel. The term parallel causes confusion. Most of us know this as the top (front) of the thighs, but some consider having the rear (hamstrings), reach a position parallel to the platform. Many are told to only bend their knees to 90°, yet such a flexion is really more of a ½ squat.

Are Squats Bad for Your Knees?

Most of us have heard that “squatting is bad for the knees.” It’s beyond the scope of this blog to go into all the details, but suffice it to say, squatting was not controversial until the early 1960s.

From what source did this weird advice that squatting was bad from the knees emanate? It started with the Journal of the Association for Physical and Mental Rehabilitation, 15(1):6 -11. In his early writings, Karl Klein, PhD recommended against “full” squats. He endorsed “parallel” squats, but it did not take long for this message to get distorted, and widely disseminated. Soon, any squatting was “bad for your knees.” This was not Klein’s original message.

Although generations of athletes, coaches, and medical professionals, along with the lay public, were exposed to the unfortunate advice that squatting would harm the knees, today we find a much more informed awareness that squatting is perhaps the key to not only athletic success in many sports but also a “quality of life” necessity.

A non-weightlifting need to be able to squat normally is the subject of many rehabilitation papers. An inability to repeatedly lower oneself to a chair and then return to a standing position, as measured by the Sit-to-Stand (STS) test, often identifies a lack of mobility and strength in the elderly.

Consider the standard toilet floor-to-seat height is about 15 inches. As a result of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, “comfort” toilets are made with a 17- to 19-inch floor-to-seat height. Initially established for ease of transition for someone in a wheelchair, the ADA-approved height is a likely aid to others lacking adequate leg strength to get on and off the “throne” throughout the day.

How Balanced Are Your Lifts?

Returning to our favorite sport, why is squatting so crucial for weightlifting success? Well, it’s pretty obvious that proper pulling technique requires great strength in the lower body’s muscles. We look to the gluteals, hamstrings, and quadriceps to break the barbell’s inertia and get it moving off the platform. Squatting develops these muscles.

Some form of squatting makes up about 20%-25% of a lifter’s daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly volume (measured in repetitions). Emphasis may be greater for those needing to improve their lower body strength. The amount of squatting also varies based on whether a lifter is in a preparation or competition training phase.

When USA Weightlifting began coaches’ education in the late 1980s the programming manual suggested the following well-established ratios:

Snatch: Squat 60%-64%

C&J: Squat 77%-81%

A) If a lifter’s result exceeds the upper number, he/she is making good use of technique but needs to focus on getting stronger.

B) If a lifter’s result is less than the lower number, he/she has is strong enough to lift more, but likely suffers from lack of efficient technique or speed-strength.

These figures often surprise many coaching candidates I instruct, especially those connected to CrossFit-type training. While this population appears to have increased their emphasis on squatting in recent years, many of these newcomers to our sport often exhibit ratios described by B above.

Check your lift-to-squat ratios and adjust training accordingly. Keep in mind, these figures are based on squatting as a weightlifter, not a powerlifter.

Lifters described by A above should place more emphasis on squatting.

-

At certain times of the year, this emphasis might mean higher reps. Lifters at the East Tennessee State and Shreveport training centers often utilize 10 rep sets (not only in squatting) to stimulate further muscular hypertrophy

-

Lifters may increase the volume of squatting by performing this exercise more frequently or in a greater number of sets

-

When prioritizing squats one might perform them first in the workout, rather than following the conventional wisdom of squatting after explosive lifts have been performed

-

With multiple-day workout sessions, it’s not unheard of to squat more than once a day, although I’d caution against too much of a good thing

Lifters fitting into the B description above can easily afford to cut back on their squatting, at least in the short term.

-

Consider squatting twice a week, rather than three

-

Reduce the number of squat sets in the training program

-

This may be a good time to focus on some alternative lower-body exercises, such as split squats, lunges, step-ups, speed squats, etc.

Squatting is vital to weightlifting success. Squat properly, be skeptical of some of the “exercise police” and their unfounded rumors, and watch your total grow.

Featured image credit: Klemens Photography