Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

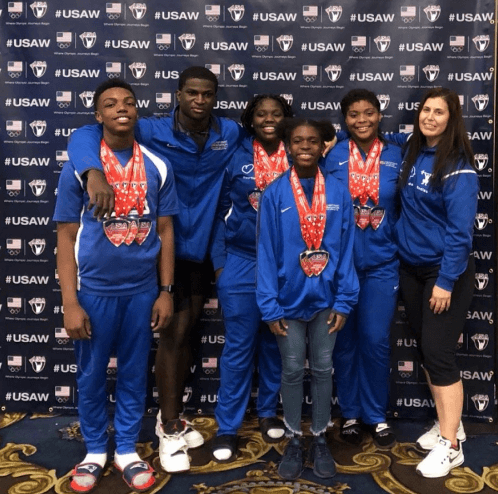

Coach Kerri Hanebrink Goodrich Interviewed by Harvey Newton

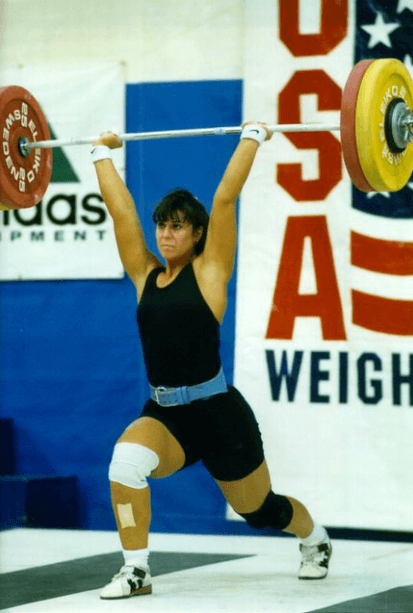

Kerri Hanebrink Goodrich began her weightlifting career in 1991. She was USAW National Champion in 1993 and 1996. After transitioning to coaching she formed Performance Initiatives, a 501© 3 organization based in Savannah, Georgia, and designed to serve transient and underserved youth ages seven through college. Coach Goodrich uses weightlifting to encourage youth to reach their potential, excelling on and off the platform.

The entire interview is available by listening to the 40 minutes podcast.

HN: Today, for our SportsEdTV weightlifting blog and podcast, we're going to be speaking with Kerri Hanebrink Goodrich. Kerri is the executive director of Performance Initiatives, Inc. She also heads up the USA Weightlifting Community Development Training Site in Savannah, which is the home of Coastal Empire Weightlifting and CrossFit Savannah.

Kerri, you have a bunch of different titles. Of course, I knew you originally as a weightlifter. We’ve done at least one presentation together on Amelia Island a couple of years ago. It's been fascinating to watch your progress in all these different roles, but I wondered if you could tell the audience something of your evolution from athlete to coach, educator, and administrator.

KHG: I think any time you make that transition from athlete to your next career, it's a little hard because you feel a little lost. You're so disciplined, focused, and goal-oriented that you want everything to be perfect.

The learning curve for me was to take small steps and to learn that everything isn't going to be perfect. But that's OK, we'll get there. I had very good mentors and was very blessed with good people around me. They kept us in the right direction, causing no harm to the community we serve. You can never do it by yourself.

Weightlifting is an individual sport, but you train as a team. You've coached some of the teams I've been on, and we travel as a team. Moving into a community leader position, one needs good leadership and communication skills in order to work as a group, not as an individual. That was my learning curve, moving from athlete to community leader. It was a really good one. If I’d known how enjoyable coaching is I think I would have bypassed the athlete part! I really enjoyed this part of it a lot better. There are so many more things you can do. Your life is no longer centered on your performance; it's about helping others reach their potential.

I am very blessed to have a lot of wonderful people around me and a very supportive husband.

HN: That's great, Kerri. When was your last performance on the national or international platform? I'm assuming you're not competing currently.

HN: That's great, Kerri. When was your last performance on the national or international platform? I'm assuming you're not competing currently.

KHG: (Kerri was USA National Champion in 1993 and 1996) No. I competed as a Masters a couple of times. We grew so fast with the team doubling in size every year. They excelled faster than I thought. Every time we have a master’s competition, we have a youth or a junior’s category. Pretty soon we’re coaching all age groups.

I'm so proud of our lifters. Some early ones are now graduating college. We have a young man who just graduated from the Mercer Medical Program and is working for a Mayo in Michigan. He's a great mentor to some of my other young athletes, too.

HN: You've certainly planted seeds and experienced tremendous growth over the years. That's impressive. Please explain to our audience the structure and the goals of Performance Initiatives? What are the criteria for involvement? What are your programs? Any specific success stories or challenges?

KHG: You might be here for a long time because they have a lot of challenges. Our goal is to work with underserved youth, opening pathways and opportunities for them. We want youngsters to stay in school, which was a real challenge here in Savannah. There was a low graduation rate and education level compared to most other communities. We wanted to motivate kids to stay in school and find a purpose.

We spent a long time praying about it, searching, talking to other coaches. One of my mentors… you know, “Big O” (Oscar Chaplin, father of USA Olympian Oscar Chaplin, III) said, “What did weightlifting do for you?” Weightlifting did so much for me. Doors opened as I traveled around the world competing for my country. It was huge.

I thought that’s how we're gonna do this, through weightlifting. A lot of these kids fight in school. It’s a challenge for them to focus on long-term goals. Weightlifting requires that skill.

We have an educational component with a tutor. Kids “earn” time on the platform to train. If the behavior isn't good, they get pulled off a platform. This helps the rest of the kids in the program. It only hurts that one person.

A friend of mine, a top-level gymnast is a counselor. She wanted to do something to help with our organization. I asked, “Could you help with life skills and trauma counseling?” A lot of these kids have gone through trauma. I had a girl whose uncle was shot right in front of her. The next day they just sent her to school.

We needed professionally trained counselors to help these kids through life events. My friend started a program, a non-profit called Heads Up Guidance Counseling (HUGS). She partnered with us, providing counseling services for the kids. We got retired community teachers to help tutor. Many that we serve are below grade level. Some have autism. Some have hearing loss and need hearing aids. They had no one to advocate for them and are held back. They feel inadequate when really, they just can't hear.

We built a community of supporters including United Way and USA Weightlifting, putting these resources under one roof. Kids can come in after school and feel safe. We work with Second Harvest to provide lunch, breakfast, and dinner.

Now kids can actually focus on their homework. Focus on life skills, anger management, trauma, and healing. They use the platform for physical activity. This teaches them the life skills needed to be successful. A lot of our athletes have never slept in a bed until they travel with us to competitions. We get a hotel, and some are sleeping in the bed for the first time.

Now kids can actually focus on their homework. Focus on life skills, anger management, trauma, and healing. They use the platform for physical activity. This teaches them the life skills needed to be successful. A lot of our athletes have never slept in a bed until they travel with us to competitions. We get a hotel, and some are sleeping in the bed for the first time.

I had a group of teenage boys in a martial arts program. For the first time ever, they were exposed to silverware, having only used plastic. They didn't know how to use a napkin. We teach acceptance of others and the fact that no one is better than another. We're doing life to improve ourselves together.

HN: You must have a tremendous buy-in from parents.

KHG: That depends on the population. A lot of kids that are latchkey kids or underserved, so some of the parents are very excited. It takes a long time to build a rapport with them to understand the importance of our program.

Some of the parents may have never graduated from high school. They may not understand the importance of education. Sometimes the parents grow with the children. The children share learning with the parents, so the family strengthens as well. It's different case by case.

HN: It sounds like you have to balance a lot of interesting challenges. Speaking of such, how is PI dealing with the pandemic restrictions on training and competition?

KHG: Don McCauley and his former wife, Suzanne Leathers, donated The CrossFit Savannah portion of the program to us. That helps with the revenue stream for our youth programs. That's had to be temporarily closed.

Our younger kids get grab-and-go meals in our parking lot. We use the hot spots there so they can get online and do homework if needed. One of the local pastors was using Zoom for online tutoring. We connect each kid with a mentor; each tutor is hooked up with Zoom. All their online work is accomplished.

We specifically partner with pastors trained in counseling. If a kid is going through depression or trauma at home, they provide counseling and identify our available services. We started that this week.

The Team USA athletes train separately. Due to the current conditions I can say these kids have never learned how to clean up a facility so well! John and I were joking about it yesterday. He says the gym has never smelled so clean.

Most of them have access to a free phone, or the schools have provided tablets. We created some online training to keep them active and in shape until we get back to normal. They take a little video and send it back to us so we can keep in contact.

HN: In terms of weightlifting specifically, what sort of age ranges are you working with?

KHG: Ages seven through college. Seven is a great age. We learned that's a perfect age since they begin to have a better attention span. We really make an impact at that age in teaching life lessons, cooking skills, getting them on track with their education.

Lifting-wise, these kids are not going to make a world or Olympic Team. But they can learn movement and coordination. They learn those life skills like how to deal with trauma and anger management, how to build rapport and respect others, the simple things that lead to success in life.

By age 10 or 11 they know the movements with PVC. They've been using medicine balls. They're climbing rock walls. If they're interested in weightlifting, they can start at that time. Weightlifting is not a sport for everyone, so we also work strength and conditioning to make them stronger and faster for whatever sport they choose.

HN: What do you do as far as weightlifting specifically is concerned? With a local meet and various age groups, what’s your general advice for when a child might start competing?

KHG: I think it's different with each child. I usually would not take an eight- or nine-year-old to a national youth meet unless they're more mature or a parent is fully engaged and bringing them and taking care of them and letting them just have the experience of being there.

It can be a pretty scary experience for a small child on a big national stage, especially now with four or five platform events. By the time kids are about eleven they're usually pretty mature. They've already been to local meets. We host events at our site or go to their partner clubs. The lifters have proven that they're mature enough to travel. They follow the safety rules and team rules, and then they're ready to go to a national meet.

It's really important for the coaches to assess each athlete. I have a girl who just turned 15. She's ADHD, with the anger component. Maybe one day she's on her meds, the next day she's off. She could be a national champion. She's very gifted as an athlete, but I would never take her off-site, ever. She's just not mature enough. She's not consistent enough. And it would be a very high risk to take her now.

HN: That’s very insightful on your part.

KHG: The coach has to know the athlete and the family and not be afraid to tell an athlete “no.” It really breaks my heart to tell an athlete “no.” But if they didn't meet our code of conduct or the school grade requirement, they don’t compete.

If we don't do it now, they're always going to think, “If I lift good enough, the coach is going to let me go.” I’ve had parents curse me up one side, down the other and the athlete throw a temper tantrum. They and their bags were ready to get on the bus to go to Nationals.

HN: Coach Kerri, what is your coaching staff like? You must have a pretty solid depth for coaches.

KHG: We work with local universities for coaching interns. I was kind of hesitant, but I love that educational part of it. Harvey, it’s a challenge to teach them, to teach the kids, to teach technique. But I really enjoy it. We had some great interns. They're like, OK, put me through the USAW course, and teach me this. They come on their time to master everything, so they won't mess up when they're coaching. They follow the same standards as the kids and are very professional.

All our interns have always connected well with our athletes and our youth. They work really, really hard to understand the program, to spend extra time with me, to understand the process, and our policies and procedures.

So for us, that's worked out well. It's been a great relationship with the community. We have one coach in his second year here. We hired him after his internship and he's going to grad school and coaching part-time. He's a great mentor, doesn't get frustrated. He's 6’ 3” about 300lbs. He doesn't have to repeat himself.

HN: You must have a number of volunteers, as well. Do parents come in and take an interest?

KHG: Our support coaches come from the military. We have a good relationship with them and the Rangers here in town are great. This is Fort Stewart and Hunter Air Force Base.

Two years ago, we had a lieutenant colonel at Fort Stewart volunteer. He was a very big advocate for our programs. We had a couple of young men that we were able to get their grades up and they qualified for the scholarship at the Benedictine Military School. The colonel helped mentor them and helped them aim toward the military. They graduated from BMS and are pursuing college degrees. They’ve just gone through training and Ranger school. Upon graduation they'll be officers and serve.

HN: That's fantastic. In terms of facilities, how many people can you train at once?

KHG: We have 15 platforms. I try to keep youth numbers at eight to 10 if they're mature enough. Otherwise we try to keep it between five and seven.

HN: USA Weightlifting had a bit of a split in their ranks with those who wanted to see technique competitions for those 13 and under at Youth Nationals. I never heard where that went. This seemed to me like an approach that has served well in other countries.

KHG: The problem was some coaches pushed young kids to lift ridiculously heavyweights that they weren't prepared for. Often the technique was so bad that you'd see these kids get injured or they would burn out before they're 14 - 15 when they could become a well-developed athlete. That could be our next Olympian.

We also saw coaches yelling and cursing at these kids. And as an adult, if somebody yelled and cursed me, I know what would happen to them. I can't imagine why a coach would verbally abuse a child and think that they're going to go lift their best on a national stage. It makes no sense.

I think USAW is having a hard time finding how to balance this. They want to protect the athlete. They came up with a maximum of 2kg jump between attempts for youth lifters. Some coaches with 13 and under were trying to jump lifters 5kg to 10kg as if they were like older athletes.

HN: After the 1984 Olympics, with Mack Trucks as a sponsor, we tried Operation ACORN. There was a template for technique and general fitness for the youngest set.

Something like 9,000 junior high students mailed in cards saying they wanted to be part of this program. We were very enthused. But we only could get one of the LWCs (local weightlifting committees), New Jersey to actually try this format. Everybody else said we're just going to do the usual. I thought that was a lost opportunity.

A problem I've seen with the occasional attempt at a technique competition is, coaches in this country can't agree on good technique. Our officials are not trained like diving or gymnastics to have the eye to look at very quick movements. The idea of technique competitions is a great one, but it’s never gotten off the ground in America.

KHG: We have so many different podcast coaches teaching different techniques, different skills. First, you have to unify what is a good technique.

HN: The age-old question: What if Lifter A is found to have what we consider terrible technique, but he lifts twice as much as Lifter B who displays very good technique. Who wins? Our bottom line has always been, how much weight can you lift?

Speaking of your Coastal Empire lifters, what does a typical training plan look like? Do you take a periodized approach based on competition schedules? I'm amazed at the number of your athletes who have lifted in national and/or international competitions in the last couple of years. How do you go about adjusting training accordingly?

KHG: That's kind of a loaded question. All coaches have a plan, and we tend to think this is it. But you have to get the athlete to buy into that. If the athlete does not understand or buy into your plan, you're just wasting time. And not every athlete is going to understand the things the same way you do.

So what I've learned over the years as part of coaching is so many people come from different backgrounds and different lifestyles. I've learned with my athletes. I never say this is what we're going to do because I'm not in the military anymore. I always say, what are your goals? What do you want from me as a coach to help you reach your goals?

I'll outline it with them, focused on matching our goals, and ask, “Are you on board with this? If you're only willing to work twice a week, this is what can be accomplished." And so you have to explain it to them that way. As a coach, you have to start from the beginning, kind of like Angel Spassov did with me.

He didn't tell me much. He put me in a qualification meet for the national championships without telling me. I think he knew if he had said, “This is what you could do” I probably would've said, “You're crazy. I'm going to stay in the military.”

But I fell in love with lifting and excelled. I had so many opportunities I would have never had before. The same is true of coaching athletes. If they've never been out of a six-block radius or been in a hotel or on an airplane it’s difficult to imagine that you could do that.

You need to show them how it can become a reality, so they believe in themselves and they believe in the same potential that you see in them. And I think that's the hardest part of coaching, designing the programming and doing all the spreadsheets and running the numbers. That's so easy. Anybody can do that. But for you to bring the athlete to the same level that you see and that you've experienced… that’s the hardest part of coaching.

But once you get a couple of athletes on board and they start sharing that story with others, it catches on fire. You create stronger and stronger team hungrier for reaching their potential and the opportunities out there.

HN: It sounds like you have created a contagion effect with the athletes. I'm sure they see long- term growth and success and learn that all this is accomplishable, but it's not going to happen overnight. You had numerous medalists in recent international youth events.

KHG: Last year in Ecuador Nia Walker took silver across the board with PR totals. Kaiya Bryant was a gold medalist in her first Youth Pan-Am Championships, and she grabbed a silver at the Youth Worlds. Her brother, Kye Bryant, was a bronze medalist in Guayaquil.

HN: I'm going to guess the local media has bought into everything you're doing. You probably get some very good coverage, which must solidify the confidence and ego of a youngster.

KHG: It does. We really work with the Board of Education to make sure that schools make the announcement about results. We want them to understand how hard these young athletes work academically and athletically. The schools are very supportive, and the kids can work online when they travel.

HN: Two last questions, Coach. You mentioned your time in the army. Tell me about that.

KHG: I was in the army when I was younger. My brother stayed in and I got out and went into the reserves. He ended up doing three tours and then doing some contract work. I was very lucky that I didn't have to see all of that. I didn't have to go to the Middle East. My time was relatively boring, in the military police.

HN: I salute your efforts on that. Finally, what are your goals for Performance Initiatives for the next five to 10 years? Also, for someone listening or reading this, how do they best contact you?

KHG: They can always contact us through our website, which is PIFitness.org. They can contact us through email. As far as goals, we really want to branch out to other locations. We have in place a policy and procedure booklet for coaching. Ultimately that's one of our goals.

More immediately is to establish a sustainable educational fund just for athletes. We had a donor who awarded two $1,000 college scholarships decided through competition. Sadly, he has passed away. We recently spoke with another foundation that was one of our first supporters. I told them we're looking for a new donor for this program, and they said, “Next year we're going to help you get that. Go in and make sure these kids all make it to college.” They've already pledged to start that up with us for 2021. We have even more kids graduating that year.

We want to continue repeating our successes. We need the people with not only the heart but also the knowledge to continue the work that we do here. Those are our goals.

HN: Within SportsEdTV we are creating communities where coaches can select and promote their own list of exercises. It’s a social media type of environment, all for free.

We’d like to come up and feature your athletes on SportsEdTV and promote what you're doing. Kerri, thank you.

KHG: Thank you, you are welcome. Our athletes love to show off their facility and what they're doing. They take a lot of pride in it. They take a lot of pride in taking care of their place and bringing their friends and family for competitions and for events that we have. We've held art shows. The kids have done these amazing sculptures. They've done cooking shows here. They're very proud of what they're doing and they're happy to show it off anytime somebody is interested.