Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Jump Back Snatch: Why?

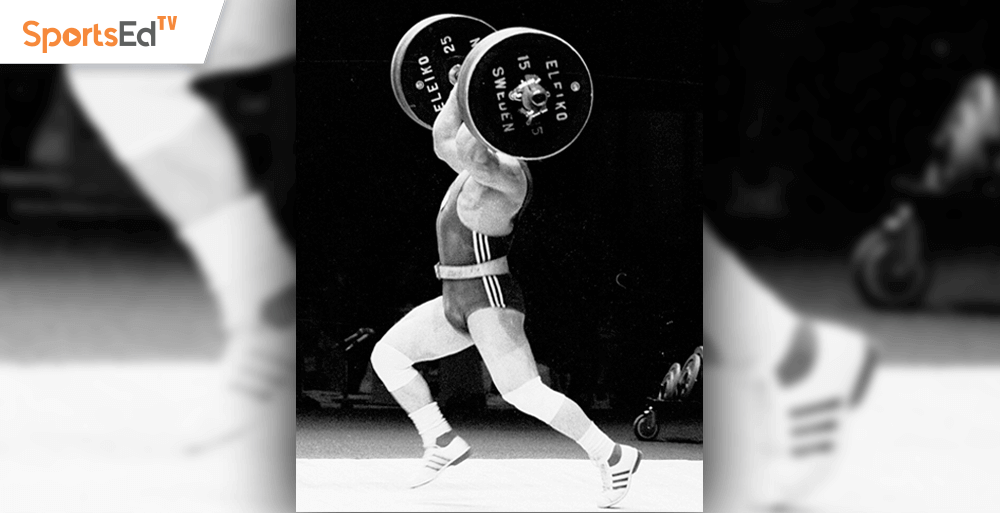

To illustrate for this blog, Rachael Bommicino demonstrates the jump-back effect in the snatch during a recent SportsEdTV filming of a weightlifting technique. The yellow line marks the front of her shoe at lift-off. The orange line marks the front of the shoe during the catch phase, showing a jump backward of 13 centimeters or a little over 5 inches.

Coach Mike Rosewell (Superior Athletes, Kansas City) contacted me a few years ago with a question about one of his lifters, Emma Nye, who was the dominant winner at the 2015 USA Weightlifting National Youth Championships.

At the event, Emma, weighing 41.8kg, snatched 41 and missed attempts with 44 and 46 (national record). She C& J'd 53kg, missing 57 twice. Coach Rosewell's question to me was about her snatch style that includes heavy contact at the hips, a looping, straight-arm swing overhead, all combined with a significant jump rearward.

Weightlifting Technique Concerns

We instruct coaches of young lifters to develop ideal techniques before introducing heavy loads or competitions. Errors allowed early in a lifter's career prove nearly impossible to eradicate later.

This was a hot topic after the recent Youth Nationals. Some wish to evaluate the youngest lifters in technique only, not the maximum weight lifted. This is not a new discussion, at least not for those with a good memory of the sport. USA Weightlifting and our then-sponsor, Mack Trucks, created Operation Acorn after the 1984 Olympics. We had tremendous buy-in from middle school kids across the country, but the program, like many others, fizzled out.

Operation Acorn ("Mighty oaks from little acorns grow") emphasized local competitions in which lifters were evaluated on technique and general muscular strength and power. In addition to snatching and jerking with a limited percentage of body weight, kids were to be tested on standing long jump, 2-hand shot-put backward throw over the head, and pull-ups.

These were fairly standard talent identification tests used elsewhere to identify individuals for weightlifting consideration. The program failed due to the refusal of all local weightlifting committees (LWCs) except New Jersey to try techniques and fitness competitions for the youngest lifters.

Note: at that time, the minimum age for the competition was 13. It's another story of how the organization came to embrace today's no-minimum age to lift in a meet.

This idea of evaluating technique presents a challenge for USA Weightlifting, then and now. Ideal, or textbook, the technique is not agreed to in this country. Our sport does not evaluate technique, only whether or not the lift is successful. Therefore, one does not need to exhibit perfect technique, as the officials' white lights appear regardless of one’s technical mastery.

If USA coaches, few of whom have comparable educational backgrounds to their international colleagues, do not agree on how to lift, how can we ever implement technique competitions here? Can you imagine the fights that would take place at a meet with the introduction of such subjective criteria?

For example, some lifters start with a wide stance and do not relocate their feet when receiving a snatch or clean. Others start with feet very close and jump them out quite a bit. Is one better than the other?

We are not diving, gymnastics, or figure skating, where judges compare performance to one standard. Minus an agreement on an "ideal" technique, we should not be surprised to see wide variations in lifting styles. This is only reinforced by the amount of content available on the Internet.

Jumping Back

Since squat-style lifting became de rigueur in the 1960s, many lifters have demonstrated a slight rearward placement of their feet after pulling and getting into the receiving position. No big deal. This is not an intentional effort to propel oneself rearward, hoping to catch the weight in a stable position.

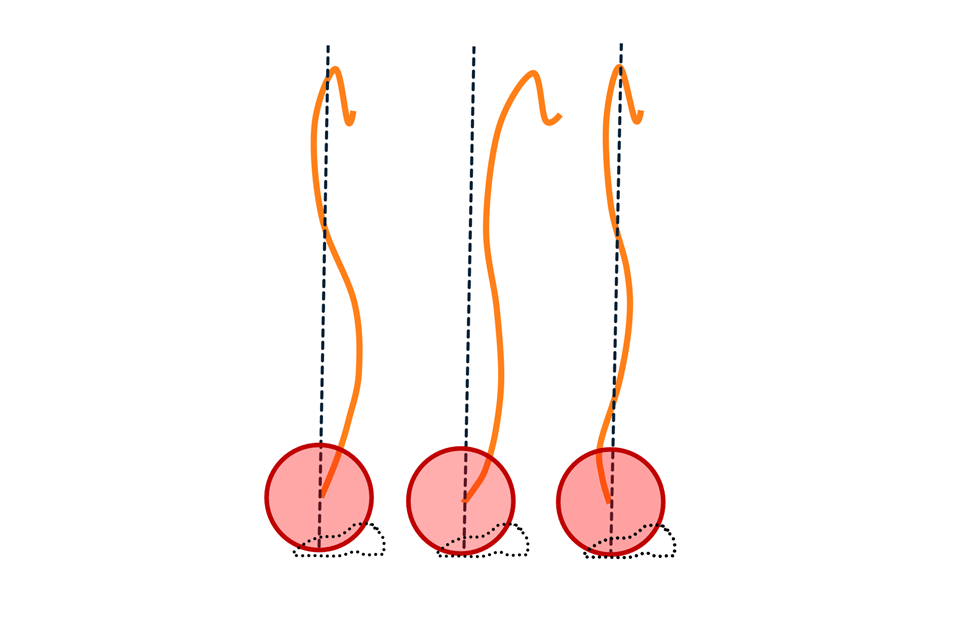

About 20 years ago, we began hearing debates about what became known as a "jump back" style of snatching. This label resulted from reviews of barbell trajectory. The trajectory is the path of the barbell from lift-off to the lockout (snatch) or rack (clean). The path is measured relative to a vertical reference line running through the center of the barbell before lift-off.

Scotland's chief trainer in the 1960s, Dave Webster, was an early source of information on trajectory. Former world champion and noted scientist Arkady Vorobyev (USSR) discussed various types of barbell trajectory in his classic text, Weightlifting (1978).

We've all seen the following chart (from Explosive Lifting for Sports):

The first type of trajectory was considered ideal. In my opinion, this is the trajectory all beginners should emulate.

The second type of trajectory involves a path that fails to move forward of the reference line. However, and this is an important point, this trajectory, in and of itself, does not assure that the lifter jumped rearward (see the Garhammer/Newton biomechanical analysis poster of Yuri Vardanian's 1978 world record). Only a measurement that includes foot placement can confirm that a lifter jumped backward.

The third type of trajectory results in a jump forward to fix the weight overhead (snatch) or on the shoulders (clean). In order to secure the barbell in a position forward of the reference line, yes, the lifter had to jump forward.

These are very subtle changes in trajectory, but small deviations, especially in the snatch, can result in a missed lift even if the barbell arrives at arms’ length overhead. By the way, elite lifters have demonstrated all of these trajectories while executing successful lifts.

Emma's Lift

Emma demonstrates a vertical 1st pull, as seen in a video I analyzed. The bar remains too far forward throughout the 1st pull, with the barbell (48kg) literally pulling Emma (41.8kg) forward.

Minus an extremely strong lower back, a lifter so positioned is likely to bring the shoulders back during the transition. The classic technique teaches beginners that the barbell travels mostly straight up during the transition, not rearward, as happens when the shoulders are pulled back. Ideally, the power position results from a repositioning of the lower, not the upper, body.

Taken in isolation, Emma's power position (end of transition, prior to 2nd pull) looks great. Remember, though, that she's moving her shoulders rearward, essentially extending the hip before the knees and ankles extend. Ideally, the hip is the last of these three lower body joints to fully extend.

Emma's trajectory, taken by itself, does not look as extreme as the visual details of her lift. During the pull-under phase, the bar passes in front of the vertical reference line, as if in the classic pattern. But this was accomplished by a huge swing forward with basically straight elbows. Vorobyev never anticipated this sort of horizontal movement, as it was presumed one would keep the bar as close to the torso as possible.

The conventional wisdom of minimizing horizontal movement and keeping the bar close is a far cry from what we see in America today. In my opinion, it is truly a shame that so many of our lifters swing the bar far from their torso during the pull-under phase.

For some, especially when the barbell outweighs the lifter, this results in a jump forward. In Emma's case, and this is a crucial message to lifters and coaches alike, nearly any technical flaw can be tolerated as long as the barbell weighs less than the lifter. Remember, Emma made her opener (under body weight) but missed her second two attempts (in excess of her body weight).

Rather than jump forward, Emma moves rearward, jumping almost the length of her shoe. This, of course, results in the bar being lost in front.

Further Thoughts

Don't start lifters off on the wrong foot! Inefficient technique may or may not lead to injury, but for sure, new lifters become frustrated by failure or inconsistency when the weights get heavier.

When teaching beginners, teach conventional techniques. Don't try to imitate the world's elite, who, in all cases, lift much more than body weight, often two to three times their body weight. At this stage, it may be necessary to utilize modifications to the conventional technique.

In response to Coach Rosewell's request for suggestions to improve Emma's technique, I made the following suggestions:

-

Review what happened (Dartfish). Go over the lift frame-by-frame and notice all the salient details.

-

Talk with the lifter and learn what she thinks she does right and wrong and where technique breaks down.

-

Work from the high blocks, first with pulls, then with snatches. When performing high pulls from this position, demonstrate a balanced, on-the-toes posture maintained momentarily at the top of the second pull. This is evidence of proper triple extension firing. Failure to hold this position suggests the lifter and the barbell are not moving vertically.

-

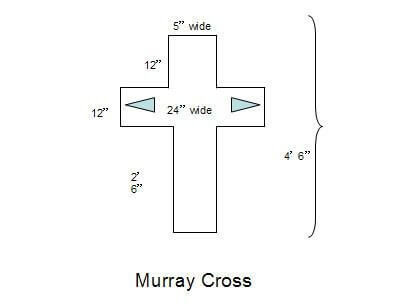

Utilize a Murray Cross for snatch practice and reward those attempts in which the lifter stays within the proper location. The Murray Cross is named after British coach Al Murray. Ignore any suggestion today that the Murray Cross has another name. The original design, when taped or drawn on a platform, included a 4" wide, 36" long center section and a cross-section measuring 22" from left to right.

I have an updated set of dimensions for the Murray Cross that suggests the entire middle section is 5" wide and 54" long. The cross-section is 24" left to right.

Conclusion

Coaches, stop arguing about technique infinitum. Embrace sports science (that which looks at what works and what does not) and move forward with a more unified approach to basic technique.

Watch our latest video: How to Snatch

TJ Greenstone’s snatch attempt demonstrates a classic barbell trajectory. During the 1st pull, the bar moves slightly toward the lifter. The path moves mostly vertically during the transition. The path returns forward of the reference (yellow) line during the 2nd pull and pull-under. Wrist extension (palms up) creates the “hook” at the top of the trajectory, confirming the bar path returns to its starting point)

By Rachael Bommicino