Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

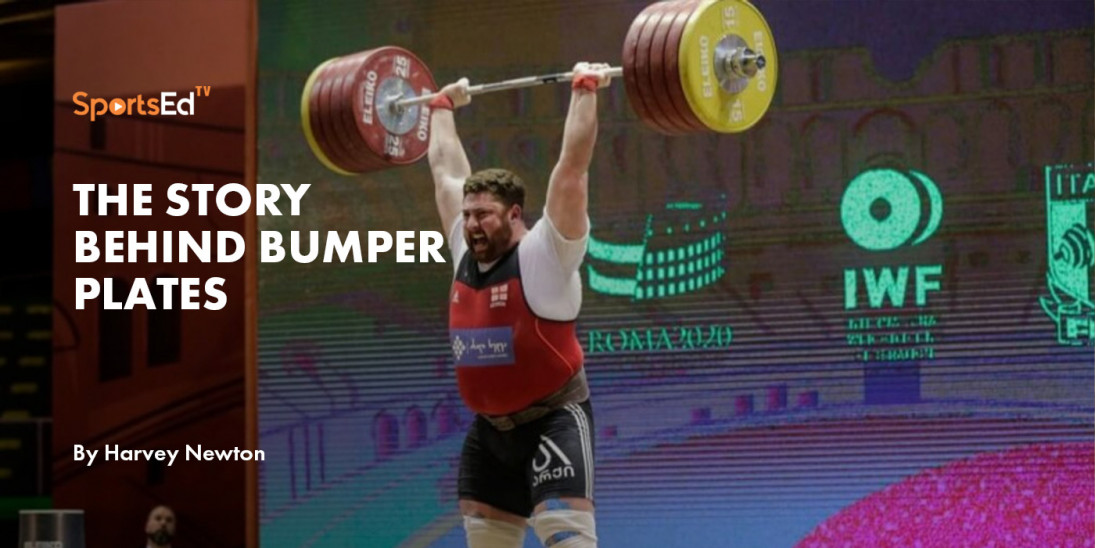

The Story Behind Bumper Plates

Since the introduction of weightlifting at the inaugural modern Olympic Games of 1896 the use of competitive equipment has gone through several changes. The early non-revolving bars with shot-filled globe ends would make today’s performances impossible.

Today’s colorful array of rubber “bumper” plates is a relatively new development. To learn how we got to today’s equipment design, let’s take a look back.

The Modern Barbell and Platform

Today’s plate-loaded barbells first appeared early in the 20th Century. The first revolving bar for use with metal discs entered the competitive scene in 1928. While the first Olympic competitors had lifted on the ground as part of track & field competition, we soon saw wooden platforms introduced and lifters competing as a separate sport.

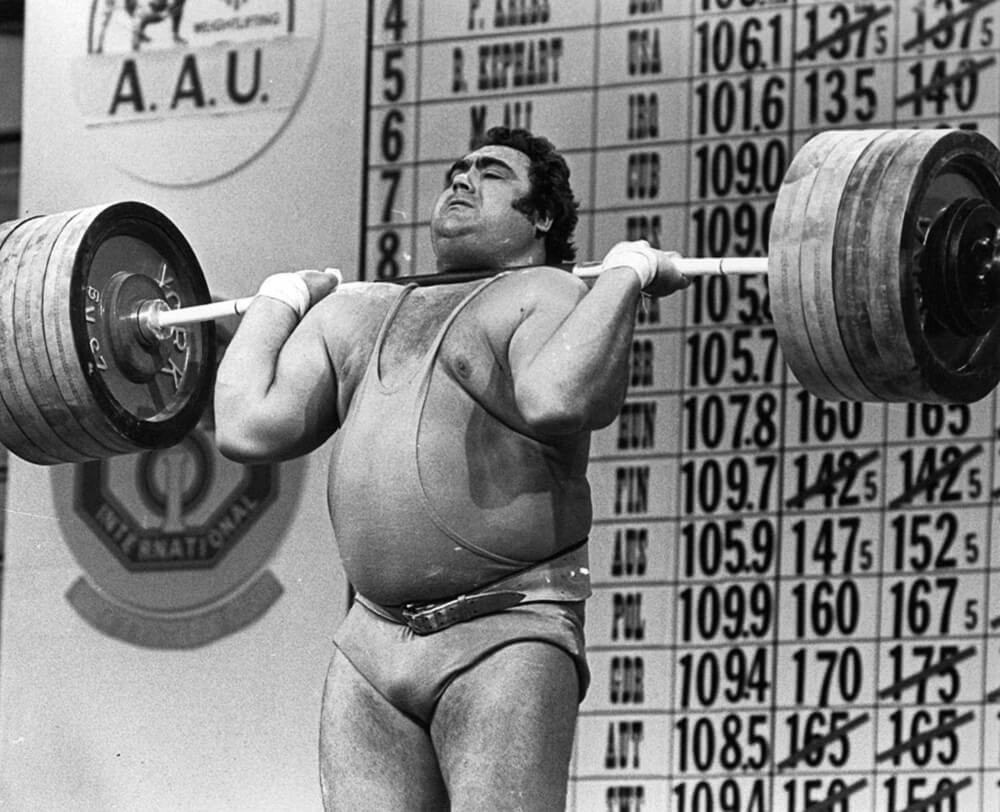

According to the rules, but also as a sign of respect for the competitive venue, early lifters were required to return the barbell to the platform under control (no dropping). Through the 1950s, most World Championship lifters did, in fact, make an attempt to lower weights from overhead. This rule was in place at local meets into the 1970s, but lifters of this era noted some differences in enforcement on the international platform. With ever-increasing weights, the times were changing. However, the requirement to lower weights back to the platform “under control” remained in effect until the eventual introduction of bumper plates. Check out online highlights of elite competition in this era to note the norms of the day.

To Drop or Not to Drop

Of course, any missed lift usually meant free-falling barbells. Often, especially when the discs landed unevenly, the result was a bent bar. Also, a few drops in the same spot on the platform were likely to cause damage to the wood. Platform repair and reconstruction were a regular part of gym maintenance as recently as the 1970s.

At the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, thin rubber matting was added to the competition platform after the first two weight categories competed. Although this hardly lessened the impact of dropping iron weights it may have helped reduce platform damage.

Rubber matting in some form became the norm. Many lifters from that era scavenged local industrial sites for discarded conveyor belt rubber, which worked very well. It protected the wood without noticeably raising the height of the barbell.

As this dropping of metal barbells became more and more accepted, we noted that many facilities simply banned the practice of weightlifting. By the 1970s it became commonplace for YMCAs and health clubs to spend money on Universal, Nautilus, or other resistance training machines and skip the nuisance of free weights, loud noise, and damaged equipment. The once-popular National YMCA Weightlifting Championships soon became a thing of the past.

Changing of the Plates

Until the 1970s York Barbell Company’s “Olympic Standard Barbell” was the norm in most training and competition venues. The heaviest and largest disc was 20kg (45lb). Any lighter discs were available in a smaller diameter, as noted in the scaled-down plate design often seen in graphic arts today. With minimal markings and no color-coding for plates, lifters of the day readily knew that a bar with four large (20kg/45lb) plates, two of the next largest (15kg/35lb) plates and secured with a set of collars weighed 135kg/305lb.

In York’s original design, the outside edge of the largest disc was a wide flange. This helped to protect the wooden platforms to a certain extent but took up a lot of space, especially as performances increased. Following another company’s lead, by 1967, York introduced a slimmer plate (with sharper edges), resulting in the easy loading of greater weights. Our new Iron Game cousin, powerlifting, was just getting started, and the new design was no doubt influenced by this new sport’s need for heavier weights in the same space.

In the early days of weightlifting, most manufacturer marks and weight designations appeared only on one side of the disc, with the other side blank. At the time, all disc markings faced inward, which led to some confusion once extra, same-sized discs were loaded. Soon, the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) introduced a rule requiring that only the first pair of plates face inward and the other plates face outward.

This was to assist the referees with properly identifying the plates and confirming the weight on the bar. But this failed to help when more than two full-sized discs (all the same color) were loaded, as no markings were visible on any of the covered plates.

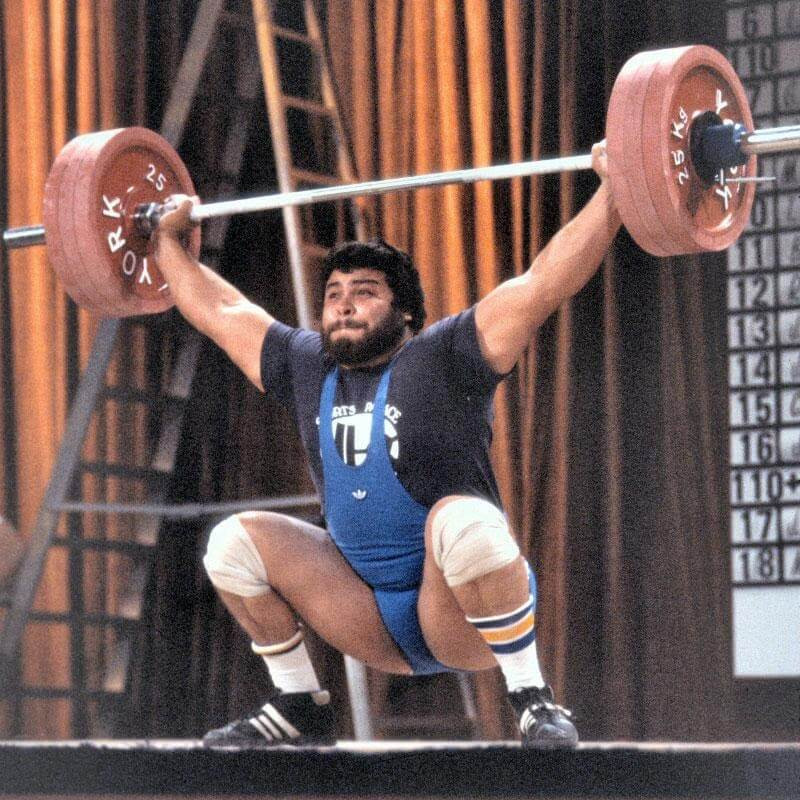

In the late 1960s, several manufacturers introduced rubber bumper plates. At the 1971 World Championships in Lima, Peru, we saw the last use of an all-iron barbell at that level meet. During the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, the West German barbell manufacturer Schnell introduced a 25kg rubber bumper plate. This was a natural progression, as world records were continuing to increase. The Schnell set eliminated the 20- and 15- kilogram plates, but the 20-kg bumper returned for the 1973 World Championships in Havana.

Sharp-eyed SportsEdTV blog readers can check out international events during the 1972-74 era and often note a mix of bumpers and steel plates, often including an inconsistent collection of smaller plates secured by the collar.

York finally added a 25kg bumper plate around 1974. I purchased one of the first five pairs for use in Florida meets at that year’s Nationals. York also had a 20kg bumper. Unfortunately for York, their smaller diameter 15kg iron plate fit nicely inside the outside edge of these larger bumpers. While this fit looked nice, after a few drops, the result was often broken discs.

Several manufacturers eliminated the 15kg plate, opting instead for the combination of a 10- and 5-kilogram metal disc set. An early adaptor of the full-size 15- and 10kg rubber bumper plates, popular with juniors, was the Mav-Rik company of Los Angeles.

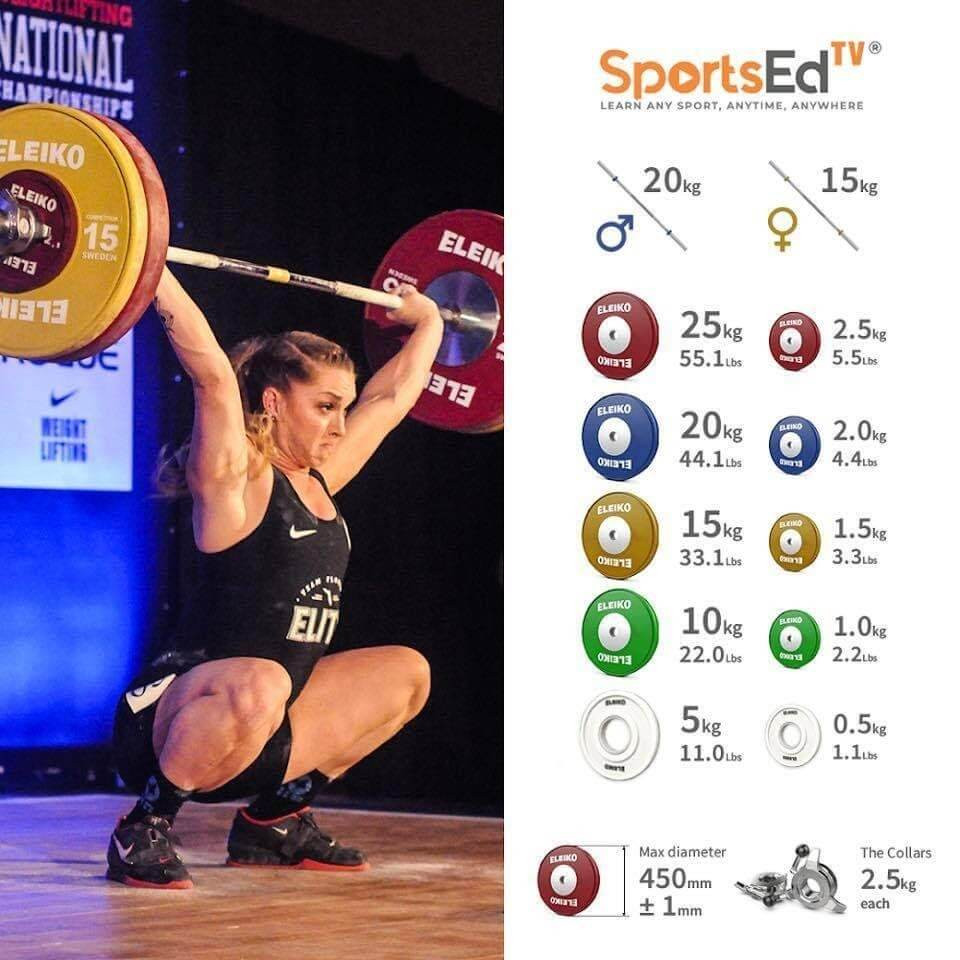

About this time, it was determined that we needed some sort of color code on a plate’s surface in order to confirm the barbell’s weight. This color-coded system, with some changes, remains in effect today and now extends to the smaller discs as well. This is a much easier way in which to determine the weight on the barbell.

The Evolution Continues

At the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, the weights were supplied by York Barbell Company. At the time, their 25-, 20-, and 15kg bumpers had a simple rubber tread surrounding an otherwise metal plate, similar to the earliest design from Schnell. While the 25- and 20kg plates held up well, most of their new full-sized 15kg bumpers broke (they did not fit particularly well), with the core separating from the rest of the disc. A number of hollowed-out 15s ended up with clocks inserted, making great staff gifts at the end of the Games. Following other manufacturers, York quit making 15kg plates of this design.

By 1980, the IWF had approved a 50kg bumper plate. These were to be used once the barbell reached 125kg (men’s bar and collars). Pity the poor lifter who took 120 or 122.5kg for his previous attempt and jumped to 125kg. The barbell certainly did not have the same feel. Never particularly popular with loaders or lifters, a few of these can be found today, often used as a doorstop. Attempting to load a 50kg plate, especially on a bar located in a squat rack, often brought a laugh or two from training partners.

The IWF approved a 30kg bumper plate following the 2012 Olympics, but there has been no sign of this disc yet. Manufacturers seldom embrace unnecessary changes since this adds to production costs. Should the 30kg bumper come along, it would solve the current challenge of loading the women’s bar to nearly 200kg in the unlimited category. Another option could be to have a longer women’s bar.

Recent Changes

It has only been in the fairly recent past that some bright individual (or group) came up with having identical printing on both sides of a disc. This eliminates the need for the inboard–outboard sequencing of plates created in the 1970s. There is no longer a right and wrong side of a full-sized disc. One possible exception exists: I have noted in several recent USA national events that the loaders have been required to occasionally turn bumpers around. In asking for an explanation, I have been told that policy (but apparently not a rule) places the hardware side of the innermost bumper facing outward and the outermost bumper’s hardware side facing inward. Why? Apparently, Anne Lehman (DC Blocks and national competitor) advised others that “No one wants to see your nuts!”.

The introduction of the new (in 2008) 1kg rule between attempts meant the small discs (so-called “change” plates) needed to be adjusted. We never before had 2, 1.5, 1, and 0.5-kilogram plates. To make matters simple, we now have large and small plates with the same numerical sequencing (25 &; 2.5kg or 15 &; 1.5kg, for example) of the same color.

Over the years, as equipment changes, the rules are often modified. Take lowering the weights after the down signal. We went from lowering the barbell under control to sort of looking like we were making an effort to lower the weights. When bumpers first appeared, lifters had to keep their hands on the barbell until the weights were below the waist. Today, a lifter must keep the hands on the bar until it is below the shoulders. There is a recent USA Weightlifting rule against “spiking,” or deliberately slamming, the weights back on the platform. Here is another subjective rule that may be difficult to enforce uniformly.

We’ve come a long way. Stick around long enough, and things will certainly change. One day, you may be able to say, “I remember the day before the 30kg bumper came along.” Meanwhile, enjoy the fact that lifting and our equipment have gone through a lot of changes and have made competitions easier and more colorful.