Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

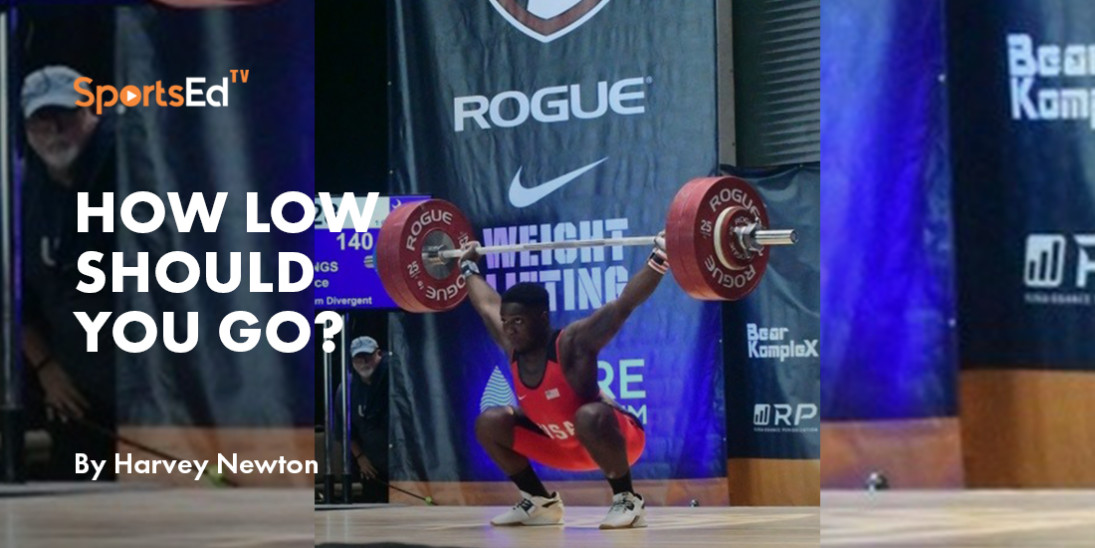

How Low Should You Go?

Coach Newton discusses the differences in bottom positions for the snatch. Much depends on the lifter.

Our previous blog on the “butt touch” rule has generated some interesting exchanges. How can this problem be avoided? What does a coach do with a lifter capable of squatting that low? Here’s a link to that blog:

https://sportsedtv.com/blog/bottom-touch-in-weightlifting/

It’s been interesting to watch recent meet videos and note the depth of squat that lifters use to snatch or clean. As pointed out in another recent SportsEdTV blog, even at international meets, one occasionally sees a power snatch or (more likely) a power clean performed. Either term applies to catching the barbell in a position in which the thighs are above a parallel-to-the-floor posture.

https://sportsedtv.com/blog/so-you-think-you-re-good-at-the-power-clean-weightlifting/

This was recently seen in the 2022 Commonwealth Games on YouTube. In particular, one woman from Nigeria racked all of her C&;J attempts with a power clean. Another woman, from Australia, easily power cleaned only her first attempt, squatting the next two attempts. What does this suggest?

Well, the first and most obvious conclusion might be, this lifter can do it, so why bother squatting? We might conclude that such a lifter has difficulty rising from a low squat position due to poor lower body strength. Or, it might be that the lifter cannot jerk any more weight overhead, so let’s keep it simple.

A new rule was added to the IWF 2020 TC Rulebook that deals with a fairly common problem related to those who choose to power clean in competition.

Rule 2.5.3.1 states, “Resting or placing the barbell on the chest at an intermediate point before its final position, producing a “double clean,” often referred to as a “dirty clean.”

When a lifter attempts a power, rather than squat, clean, it is not unusual to see the bar racked low, slipping slightly down the shoulders during recovery and then moved up into a jerk position after standing. This may also happen in a squat clean that involves a tough grinding recovery or in the seldom-used split-style clean. Racking the barbell low and/or having it slide downward, followed by moving the weights upward makes this a two-part movement, thus officials should turn down this “dirty clean.”

But what about catching the snatch?

Background

Today we seldom see, except perhaps at master’s meets, a lifter utilize the split style of snatching or cleaning. But this was very common in the early days of competitive lifting. In the split style it was normal for a lifter to adjust the depth of their receiving position based on the intensity of the lift, that is, a lighter first attempt split snatch or clean might be caught “high.” With heavier weights on successive attempts, the lifter needed to achieve greater split depth.

As a review, the three styles of snatching are explained here: https://sportsedtv.com/sport/weightlifting-instructional-videos/how-to-snatch

Since the rules have always stated that the feet can be the only part of the body in contact with the platform, the big challenge in the split style snatch was to avoid a “knee touch.” As we have previously discussed, doing so requires the officials to be able to quickly note a possible knee touch while checking to be sure, in the snatch, that no press-out occurs. Today’s location of the officials may, at times, preclude them from being able to spot a knee touch. Most of today’s officials are pleased not to have to judge split-style lifts!

This reminded me of Stan Stanczyk, USA’s great lifter of the late 1940 and early 1950s. Stan won five consecutive world champion titles (in three different bodyweight categories) and was 1948 Olympic Champion. At those Games, Stan split snatched 132.5kg for a new world record. The judges approved the lift, but Stan “shook his head and tapped his leg to indicate that his knee had scraped the floor” (The Complete Book of the Olympics, Wallechinsky). How many lifters would take such action today?

Of course, many old-time split snatchers could not get their lifts passed today due to the current strict enforcement of the “press-out” rule. Again, we are perhaps lucky not to see the split employed very often.

Catching a Squat Snatch

Back to the topic at hand, where to catch a squat snatch. The ability to squat low (or not) is related to flexibility and to segment lengths. In some cases, one might include muscle mass as another variable for consideration.

However, the same concept of catching the lift as high as possible is applicable to the squat style of lifting as in the split. In his seminal text, A Textbook on Weightlifting (1978), Professor (and World and Olympic Champion) Arkady Vorobyev describes the action of turning over the bar in either the snatch or the clean as a “hook” (not to be confused with the hook grip). When looking at barbell trajectory, the hook is measured from the highest point of the pull to the point where the catch (snatch) or rack (clean) occurs. It is assumed that once this point has been reached, the lifter will arrest the descent and recover.

In Charniga’s translated works of Roman, the author suggests that research shows (no doubt with fairly elite lifters) that the hook in a squat style snatch should be 5-9% (mean = 7.5%) of the total distance needed to successfully snatch the bar. While this may be too much scientific detail for many readers, it does suggest that the turnover phase of the snatch should be executed quickly, and the lifter should “apply the brakes” once the barbell is locked out.

The modern bar allows for a quick flip of the wrists, from pulling under the bar to locking out the bar overhead. Done properly, there is no wasted movement. We do see a number of lifters today who, while moving under the bar, keep a neutral or straight wrist. This may be due to swinging the bar forward or leaning backward excessively. Regardless, this is not the quickest way to get under the barbell. With the bar far from the torso while going under, the hook is wider (takes longer) than those that pull under and catch in the traditional manner.

Catching High

Sweden’s Patricia Strenius presents a good example of a lifter who does not descend into a low squat position after locking out her snatch attempts.

Patricia Strenius catches her opening snatch attempt at the 2019 IWF World Championships well above parallel.

Another example of a lifter who does not descend deep into a squat position is 2019 USAW National Champion (+109kg) TJ Greenstone, a SportsEdTV Senior Contributor, who graces the cover of our ebook on the snatch.

National Champion TJ Greenstone is another good example of a lifter who catches maximum snatch attempts at parallel. He runs no risk of having a “butt touch.”

No amount of flexibility work will result in either of these lifters having to worry about a butt touch with a neutral spine. But what about those few lifters who can achieve a butt touch while snatching?

Too Flexible?

Allow me to make a generalized statement about flexibility, namely, that for the most part, females often exhibit greater ranges of motion around certain joints than do males. Also, some relatively novice lifters, both male and female, seem to think that after pulling upward on the barbell it’s time to dive into the bottom position. Thus, they hit bottom on both light and heavy attempts.

One female lifter with whom I have worked in the past always dropped into a low squat position before the bar was locked overhead in the snatch. This often resulted in the bar pushing downward although she had no further squat depth available. The result was often a “bending and extending of the elbows,” or what is generally categorized as “press-out,” a rules violation.

What we found was, she knew she could squat into a deep position and simply sought that posture on all lifts regardless of when or where the arms reached lock out. The solution? We worked at turning over, locking out, and stopping the downward descent while in a higher squat position. This “progressive depth” catch can prevent the above-mentioned problem. Take a look at Strenius’s three snatch attempts at the 2019 World’s.

Sweden’s Patricia Strenius catches 98-102-105 progressively lower.

The final attempt was lost forward.

Let’s examine another example, this time Leila Cook of Arizona. Leila is the USA National Junior Champion at 55kg and has continued to improve over recent years. Noted biomechanist John Garhammer, PhD, keeps me informed of Leila’s promising progress. She has, however, been known to squat so low as to contact the platform during maximum-effort snatches. Here’s an example from this year’s IWF World Junior Championships where Leila made 75kg and 78kg, before failing with this 80 kg final attempt.

These are screenshots from a video with a poor image on YouTube. To accurately measure the various characteristics of this lift, we need to have a side view. Of note is the tremendous height of Leila’s second pull (fifth photo). This height suggests she is capable of snatching greater weights (and she has). Remember, if this is the high point of the pull, a quick hook or turnover should achieve lockout with the lifter in a fairly high catch position (sixth photo). But note the increased depth (reference the yellow arrows against the scoreboard graphics) Leila seeks after the lockout. This resulted in a butt touch and “no lift.”

When a lifter can obtain a low squat receiving position, fine, go for it… but don’t let the descending barbell either drive the athlete into a lower squat or cause a press-out. Learn to arrest the descent and go no lower than is necessary to secure the weights overhead.