Health, Physical Education

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Does Elite Sport Increase Sport and Activity Participation?

The Question

The Western Alliance, an Australian academic health science center, asked the question in a recent article, “does elite sporting success influence public participation in sport and exercise?” The conventional wisdom being that the better a nation does on the international stage, e.g., the Olympics, the more likely that the rest of the country will rally and get on the sport and exercise bandwagon.

It turns out the answer might not be what you expect.

The Influence of Sport on Society

Several factors contribute to the influence elite athletes have on the general population. For example, are elite athletes healthy role models? Yes and no! The Mayo Clinic revealed that, in general, elite athletes live longer than the general population. Cardiovascular athletes and mixed/team athletes have reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases and cancer. However, there was no reduced risk for power athletes. Advertising and promotion of unhealthy food at elite sports events by manufacturers and retailers creates a negative impression. Fast food restaurant McDonalds held a large food contract at the Olympic Village until 2017 and the restaurant at the Olympic Village was so busy at the Rio Olympic Games that athletes who ordered fewer than 20 items were served faster. Usain Bolt reportedly ate 100 NcNuggets® per day.

Image 1. Line at McDonald’s Inside the Olympic Village

The Olympics are now considered a breakeven endeavor. To counter the lack of increased funds coming into host cities, there is a call to increase the cultural, social, and economic legacies of the Games as measured by philanthropic giving, crime rates, and sport participation. Philanthropic giving by local companies increases before, during, and after the Olympics but individual giving is more difficult to track. Robert Baumann, who studies the economic impact of sports, reported that crime rates have been shown to actually increase 10%, thought to be due to a rise in visitors to the host city.

Sports, including professional and amateur competition, have a powerful impact on society, especially as sports at all levels pump money into local economies in terms of travel, hotels, restaurants, and jobs. Yet, the overall economic impact of sports (largely reported from cities opening new stadiums for professional teams) has been reported to be 1/10th of 1 percent, much lower than what most people think.

If elite performance on an international stage leads to increased sports and physical activity participation at home, then it seems like money well spent. If the answer is no, does that mean we should reconsider how we fund elite sport to also support preventive programs?

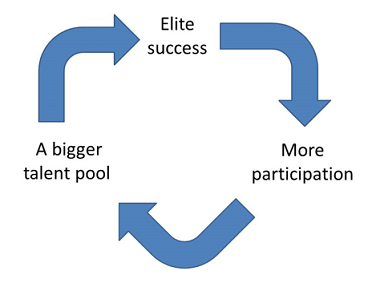

The Virtuous Cycle of Sport

Unfortunately, elite sporting success does not positively influence public participation in sport and physical activity. The Western Alliance article cited that in the UK the exact opposite occurred—the more medals won, the less participation in sport and exercise! The thought of the virtuous cycle of sport appears not be true.

Figure 1. The Virtuous Cycle of Sport

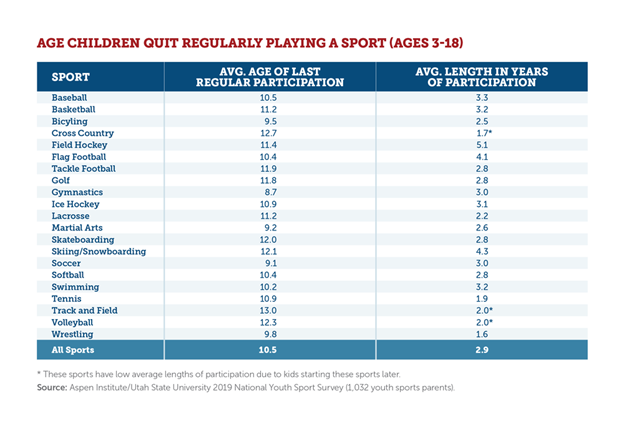

The Western Alliance cited results from several studies that sports did not have a “trickle-down” effect in sport and fitness participation after the Olympics in the UK and Vancouver, or after the height of tennis superstardom in Germany. There appears to be much more than the virtuous cycle of sport needed to influence exercise and sports participation in the general public. First, participation in organized sport across the lifespan is actually very low. Participation across the life course is most popular for children and adolescents, but recent surveys suggest that the popularity is not as high as it once was. In fact, the following chart (Table 1) shows that not only are fewer kids playing sports and some of the most popular international/Olympic sports (Baseball/Softball, Gymnastics, Soccer, Swimming, and Volleyball) are experiencing the most significant decreases (US Data 2008-2020):

Table 1. Percent of Children in the US That Participated in Sports in 2020 but that the kids that are playing sports are not playing for as long (Table 2):

Table 2. Age at Which US Youth Sport Participants Stop Playing Sports

Second, in adulthood there are transitional life stages (college, career, and marriage, for example) that have a negative impact on sport participation that contribute to a continual decline in sport participation throughout adulthood. Third, adults are more likely to be active through general PA pursuits than through sport participation, so sport policy that focuses on increasing participation numbers may not be the most effective strategy for lifetime physical activity since most people drop out of sport by early adulthood.

Fourth, many countries use public funding to pay for the training and competition of their elite athletes. And, since many national governments invest more in elite sport than in community or participation-based sport, even when elite athletes only represent a very small proportion of the total population, the gap in the cycle of sport is even more pronounced. Similarly, the objectives of elite sports investment differ significantly from those of community participation in sport. In elite sport, the impact of sport as an entertainment industry drives high-profile participation by a very few in national and international events. In community participation, the policy focus is on becoming and remaining physically active across the lifespan through participating in sport and physical activity. How do we, then, close this gap?

Long-term Athletic Development for a Long-term Solution

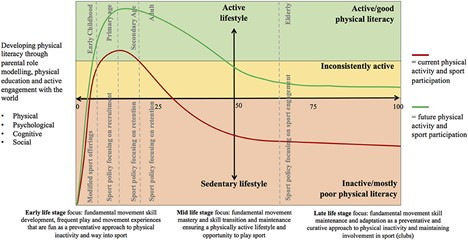

Long-term athletic development is a framework for physical literacy, which is foundational and critical to living an active lifestyle. Long-term athletic development offers a solution to the lack of connection from elite athletes and the general population by creating a cradle-to-grave movement system that embraces both ends of the continuum in one framework. Many existing LTAD models provide pathways to performance and to recreational competition, with the notion of continued participation in physical activity after athletic participation ends, but this, we know, is not the most effective strategy.

A recent article on creating a sports and physical activity framework (SPAF) suggests that the original model for sport participation met the needs of competition but not participation. This would certainly be a factor leading to the disconnect between elite performance and population participation. The updated focus is on participation, specifically aimed at increasing levels of sport participation and physical activity across the life course.

The long-term athletic development framework as outlined in the SPAF accounts for physical, psychological, cognitive, and social components of sort and physical activity from early childhood through the elderly years (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. The Sports and Physical Activity Framework

The figure shows strategies for policy makers to focus on to get and keep participants into sport across the lifespan, with focus shifting from modified sport offerings to recruitment, to retention, to engagement. Such policy and participant focus would positively impact the likelihood of people becoming and remaining physically active. The more physically active the participants are, the more likely they could be recruited into sport, and the more likely they can increase their levels of physical literacy. The key tenets of the lifelong physical literacy pathway, according to the authors of the PSAP are:

- Parents, physical education teachers, and the wider physical activity ecosystem environment are important facilitators of developing physical literacy.

- Development of people's fundamental movements skills is critical (the physical component of physical literacy), but for people to become (holistically) physically literate, developing the psychological, cognitive, and social elements are equally important.

- There are critical transition points during early life stages for sport policy makers to consider. Every stage requires a different policy focus, and these move from offering modified sport as a means to recruiting very young children into sport, to retaining adolescents and adults as sport participants, to retaining the elderly as actively involved and engaged in sport clubs.

- There are three major life stages in regard to developing or maintaining high levels of physical activity that in regard to the intent of being physically active broadly range from a preventative to maintenance, and then a curativeapproach with advancing age, and

- An increased level of physical literacy mostly leads to high levels of physical activity (active lifestyle) and that a poor level of physical literacy mostly leads to low levels of physical activity (sedentary lifestyle).

Changing the Sport Model to Include Elite Performance and Community Engagement

It is important to state that the end goal is not to diminish the importance and national pride that comes from high-profile, elite performance. The end goal is to provide more equitable opportunities for all to participate in sport and physical activity throughout their entire lives. Researchers and practitioners have advocated for more equitable changes to the youth sport system (e.g., long-term athlete development), especially at the youth level, yet their recommendations have largely been overridden by the existing model that serves only the few.

Creating a cradle-to-grave model that meets the needs of both the developing child and society is a successful tool to cultivate elite performers. At a time when the youth sport model has become more professionalized, a recent call to action in the US has been sounded. The series of recommendations can be considered for filling the gaps in other countries, which already have a centralized sports structure, lacking in the US. These recommendations include:

- engage all stakeholders in all contexts of sport and physical activity to achieve collective impact for the lifelong outcomes of physical activity across the lifespan.

- provide universal access to fun, safe, and affordable opportunities for play, sports, and physical activity across the lifespan for everyone.

- balance investment in play, sports, fitness, and life commitments to promote healthy habits that increase engagement in physical activity and sport, and

- share the vision for the long-term physical activity and sports through promotion of the important concepts of development, health, and wellbeing across the lifespan through sport and physical activity.

Nations such as the Netherlands, the UK, Finland, and New Zealand are exploring these recommendations to help stimulate physical activity through national policy, which includes funding support for increasing community-level sport participation. Let’s hope all nations follow suit.