Health

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

What Youth Sports Coaching Should Look Like

Youth sports can bring communities together around a common goal- the success and happiness of children. Sometimes, however, the tactics and strategies involved in the process are called into question. The recent debate surrounding the Icelandic documentary, Hækkum Rána, and the coaching methods of Brynjar Karl Sigurðsson, the girls’ basketball coach of the program, has brought much needed global attention to the topic of coaching practices in youth sports. Parents and the general public are passionate about their view, whether they support Coach Sigurðsson’s coaching style, or they subscribe to an alternate coaching philosophy.

The question remains, which side is right? There are two sides to this and every story. To answer the question, we must consider the larger question: what is the aim of youth sports in our society? Then we can decide which side of the argument gets us closer to our societal goal.

Most international sporting organizations, Icelandic and other national sports organizations, and private coaching organizations agree—the aim of youth sports is to provide positive youth development through sport. This positive youth development includes the nurturing of the physical, mental, technical, and tactical elements of the sport. There are a couple of different models we can look at for guidance of positive youth development.

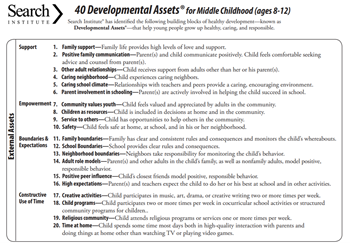

First, the 40 Developmental Assets have been formulated to help us recognize that certain “building blocks” of healthy development support children and adolescents growing up to be thriving members of society. The Search Institute has developed age-based questionnaires that “are reliable and valid assessment of the strengths, supports, and social-emotional factors that are essential for young people’s success in school and life.” The more assets the child has, the more likely they are to thrive now and, in the future, the more likely they are to be resilient in the face of challenges, and the less likely they are to engage in high-risk behaviors. It can be argued that some of Sigurðsson’s methods seem to be effective to build external and internal assets for those on his team, such as in developing a sense of community and sense of purpose. Here are the 40 Developmental Assets for the age group he coaches, 8-12-year-olds. Watch the documentary again and score how many assets he fosters and how many are excluded.

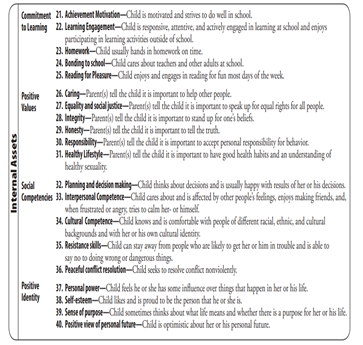

Another way to look at the commendations/recommendations for his program is to look at the program through the lens of physical development. The Youth Physical Development Model, created by Drs. Rhodri Lloyd and Jon Oliver of the UK, shows the ages and stages for developing young athletes. There is a model for boys and a model for girls. This is because there are different rates of growth and development for girls and boys. The area with the darkest color for each chart indicates the period of greatest adaptability of the 10 fitness attributes. Since girls typically mature ahead of boys, their ages are between roughly 10-14 years of age (there is a span across growth and development at which each sex reaches the age at peak height velocity (the growth spurt, also known as adolescent awkwardness). For boys, the ages are about 12-16 years. This age is considered to be a critical age in the athletic development of both boys and girls as it is the time that if the building blocks for success are not developed, dropping out, burning out, and injury are of chief concern. Sigurðsson’s program has many qualities to build on, such as having a structured strength and conditioning program, setting the limit for practice and competition to no more hours per week than the ages of the girls in years, and the inclusion of parents in their daughter’s experience.

The two prevailing models of youth athletic development, Istvan Balyi’s Long-term Athletic Development Model and Jean Cote’s Sport Sampling model, both emphasize that serious competition should not occur until closer to ages 13-15, the next age and stage for the girls involved in the program. This means that the intensity of the competition is not developmentally-appropriate for them, generally. Since boys of the same age are typically developmentally behind girls in that age group, it is not recommended to have such laser focus on competition and winning for either sex at this age and stage, and it is not warranted for them to challenge each other.

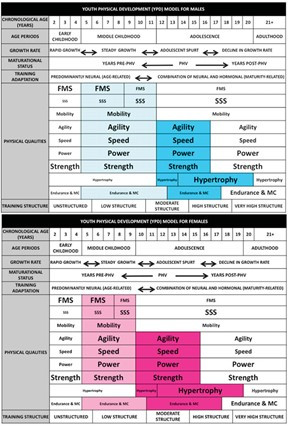

The counter-argument is that for those girls that reach their age at peak height velocity ahead of the rest of the girls in their age range (known as early maturers), they may be developmentally ready for the rigors of competition. The proposed solution to having such a discrepancy in the ages to physical maturity in most programs is a concept known as bio-banding. As this infographic from Science for Sport shows, the solution may be in grouping young athletes interested in competition with other young athletes by growth and maturation, not chronological age (years from date of birth).

This would certainly provide context for the competitive nature of some programs and provide opportunities to meet every child where he/she is. Otherwise, we are creating watered-down versions of the adult game, ignoring the complex nature of growth and development, both physically and emotionally, setting up too many kids for failure. In the United States, for example, this has led to 70% of kids dropping out of youth sports by age 13, with the number now tending towards age 11. Kids are not miniature adults.

The general principles of the International Olympic Committee, as shown in this infographic from YLM Sport Science, tell us that not only must we be aware of the vast differences in physical and emotional maturity but also that a wider definition of sport success is needed. The adult-focused product goal of winning is quite often not even in most kids’ top 10 list of reasons why they participate in sports. It is the number one reason many kids stop playing sports (there are many reasons for this but the emphasis on winning at the expense of process goals such as motor skill development and self-efficacy are often listed). Coincidentally, motor skill confidence and competence and having fun are key determinants of lifelong participation physical activity.

From the mental perspective, most evidence suggests that yelling and other demeaning behavior is not in the best interest of the child. According to SportsEdTV Senior Contributor, Kristen Dieffenbach, yelling “is not a long term healthy motivator. It is a motivation not to get yelled at again (away from) rather than toward doing. There is differential yelling (loud voice) which might be appropriate at critical moments to get an athlete’s attention, but it is not yelling at a player. A coach might care and get frustrated and yell but that doesn't justify losing your temper or yelling- it is part of emotional maturity to be able to contain your emotions.” To keep the emphasis on overall player development with the aim of a better society through sports, we must meet kids where they are, both physically and emotionally.

Sports are often the vehicle to develop healthy habits that last a lifetime. If we take the best information, we have from the science of youth athletics and positive youth development, we can build a quality sports program that is developmentally appropriate for all kids. Choices must be available to attract all kids to sports. This includes providing some opportunities as Sigurðsson has but recognizing that to positively influence more kids to play sports, a different tact may be preferable. There are two sides to this story. Some aspects of the story are in alignment with positive youth development and proper physical development. Some aspects of the story, such as competitive emphasis and disproven mental strategies, are not in alignment. We need to know who is coaching our young athletes and what qualifications they have for the role.

It will be interesting to follow this story to see how many of the girls continue to be physically active throughout their lives. If the data follows current trends, there is an increased risk for sports burnout. As coaches, we must do better to follow the latest in sports science and positive youth development. Our kids depend on us. Society depends on us.