Mental Health, Physical Education, Swimming

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Developing The Coach-Athlete Relationship

Coaching athletes and training athletes are not the same thing. Coaches like to equate the type of training, volume of training and skill instruction as doing their job as a coach, but in my mind that is simply training their athletes. Coaching is about the person and not what the person is doing. If coaches worked extremely hard to develop their athlete communication style, athlete self-belief would be enhanced and the training part would simply come along for the ride.

If we look at the people who might play a direct role in the development of young people, you might consider family, friends, teachers, and coaches as the main actors. Outside of that you have institutional environments, cultural norms, public personalities, and the various forms of media as indirect players who shape our thinking and direction. Although the indirect actors can have a significant influence, it’s the direct actors who are or should be the most instrumental in helping our young shape who they are, what they stand for, and through that process the ability to develop the tools that will help them be successful in everything they do. In my mind the key players on the direct side are the teachers and coaches. I don’t mean to minimalize family or friends when I say that, but athletes seem more amenable to what teachers and coaches say and regardless of whether mom or dad had the exact opinion, the athlete will respond to the coach/teacher persona more readily than they will their parents. This doesn’t make the teacher/coach the exclusive deliverer of life advice since it should be considered a shared responsibility, but the coach/teacher has to accept the role they play and be respectful in an inclusive way when developing the young student/athlete. With social media creating an exponential expansion inside the arena of indirect influence, I think it’s more important than ever that coaches recognize the role they play in societal structure. I think that every person who chooses to fill the role of being a coach should recognize that developing the athlete should always take a backseat to developing the person. In my mind if you develop the person, you increase their ability to perform on game day and understanding how to develop that strong, respectful relationship between an athlete and a coach is a multi-faceted process that starts when they are young and continues well after their retirement from their sport.

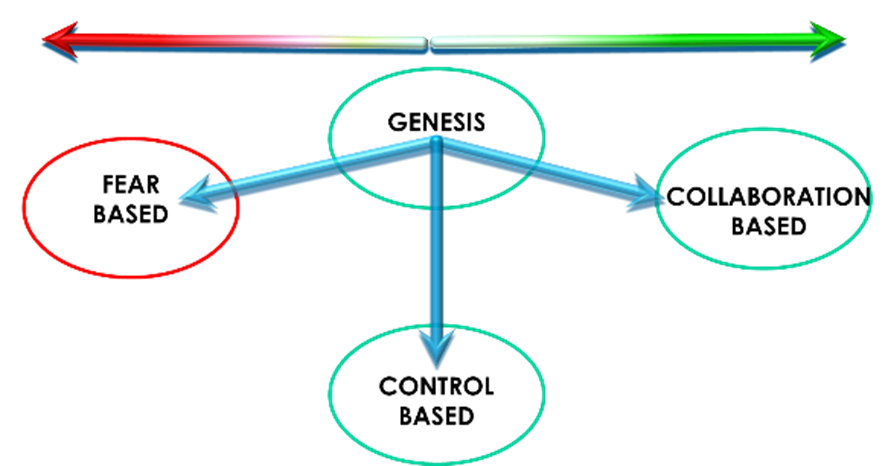

How does a coach cultivate that respectful relationship with an athlete and what are the steps that develop the fabric of their mutual respect and trust? It all starts with the path any coach chooses to follow with regards to how they coach their athletes. In looking at the coaching spectrum, coaches have a choice of employing training/playing environments that produce a fear-based to a collaboration-based style. If your athletes are worried about being yelled at, getting playing time, being called out in front of their peers or being asked to do disciplinary activities because they fail or mess something up during training or competition, then your style is fear based in nature. This style might have limited success at the elite end of athlete spectrum but has absolutely no place at all at the development end. Control based programs where athletes worry about what the coach thinks of their technical or tactical skills can still produce enough apprehension to where the training environment will cease to be fun based. I fully understand that pushing athletes to the limit is what gets the best out of them, but I disagree that it must be enacted at the expense of those athletes who don’t meet the training focus, standards, or expectations. In my mind there is no place for a fear-based option in today’s world and I would urge coaches to follow a more inclusive control based or full collaboration-based environment that helps athletes feel comfortable with developing ownership over their genetic gifts.

I’ve had discussions or been privy to discussions with elite level athletes and the one point that surprises me is how many of them were coach dependent on their performances. In my mind I feel like athletes at the elite level should always have a high level of autonomy, but in many cases, athletes want nothing of autonomy and want to be led every step of the way. There is no question that this system has worked and will continue to work, but there is life after sport and there are a number of athletes who end their careers with no tangible learned skills and abilities to make their transition into life. I’ve thought about this situation and can see a dual issue. Athletes will always be a product of their environment and coaches aren’t very good at relinquishing control when it counts the most. The onus in this case is on the shoulders of the coach. It’s natural for coaches to live vicariously through their athletes and when coaches start believing they are the make or break of an athlete’s performances, they can inadvertently coddle the athlete’s ability to stand on their own two feet. When they over coach and don’t help the athlete understand how to manage themselves at the elite level, they take away important learning opportunities that will impact the athlete as a person. This starts at the developmental level, and if coaches aren’t willing to relinquish some level of control, they will spawn athletes who aren’t self-dependent when it counts the most.

When you deal with athletes who perform in tactical based sports it’s essential that they can think for themselves, and continued pressure that correlates performance with playing time will hinder all aspects of that athlete’s development. Sports like soccer, golf and tennis require athletes to solve problems with quantum like thinking, while linear sports like swimming, track and field and speed skating can be very drone like in performances. There is no question that quantum sports require a high level of autonomy, but there is no reason why linear sports can’t walk down that same path. In the following discussion I will discuss all the areas that will help athletes develop ownership/autonomy, and I believe that the process must be started at the developmental level. Athletes who prefer to be drones versus thinkers are without question a product of their environment, whereas athletes who are given ownership and some autonomy by their coaches will have a greater potential to flourish in both sports and life.

All athletes, and especially athletes at the developmental level are highly concerned with pleasing their coach. Gaining your trust and recognition will drive athletes to do amazing things, and when in this position of power, it is critical that the athlete understands that your relationship with them cannot be conditional upon their performance on the field of play. Athletes should never feel like they have to perform in order to be recognized or loved, and it is critical in your position of power that you make that point clear to them.

When I meet with or begin coaching a team for the first time, one of the first things I will tell them is that what they do in competition will have no reflection on how I will treat them as a person. How I treat them as a person will be based on how they interact with their coach and the people around them.

When you take that pressure off the table for athletes, you give them a greater chance of being successful. Mistakes are simply learning experiences, and they should always feel that you have their back no matter what.

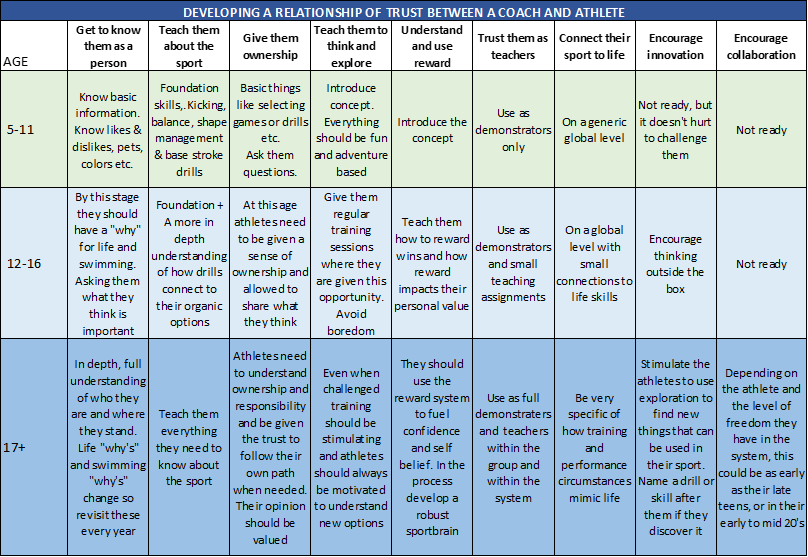

As I get into the various areas that are the underpinnings of coach/athlete relationships, I’ll start by sharing a table that illustrates how the relationship can be developed based on the age of the athlete and then provide more detail as to how the relationship can be cultivated.

Understand the person inside the athlete.

All initial conversations should have nothing to do with their sport and works best if you take the time to listen to them without injecting opinion. Get to know their likes and dislikes, their current career goals, what music they listen to, what shows or movies they love to watch. Ask them to relate their “why” as a person and how they see themselves within the world around them. The pace of these discussions will differ since some will be careful before they trust you, but as you find common ground with them, they will begin share more and more of their harbored thoughts. When appropriate share an anecdote from your life that relates to what you’ve heard. It doesn’t need to impressive or soul baring; it just needs to help them feel like your journey at their age was similar. That common ground is important because it illuminates a shared path that might calm the fear of sharing inner thoughts with a “stranger”. In that initial getting to know the person inside the athlete period, small mistakes can undermine earned ground, so ALWAYS take notes, try to put yourself in their shoes during quiet thinking time about them, and remember it’s better to prompt and listen versus interject and say the wrong thing before you know that they trust you.

In my first meeting with an athlete, I asked them what they did when they really wanted to unplug and get away. The answer was to visit their local national park and walk the Gettysburg battlefield. I asked why and what it meant, and his reply was one I thought well beyond his years and belied his grades in school. I asked him how such an insightful person could have average grades and with a small smile growing on his lips he said that he’d never found anything interesting to study. That small smile told me that he knew that I’d seen something in him, and he liked the fact that I’d paid enough attention to notice that. That led to what might interest him and as we evolved the friendship, I really grew to admire his peace of mind at such a young age. The result of this first meeting was a much stronger more respectful coach/athlete connection and subsequent meetings with the athlete explored poetry and books that had no connection at all with sport.

Depending on the athletes age, the human side might take several conversations to establish a strong report, but the key is allowing it to happen by listening more and finding opportunities to show that you care. Jot down notes about athlete interactions since in the early stages of the relationship they should be reviewed prior to subsequent interactions or discussions. As you get to know your athletes you will need these notes less and less to refresh memories and thoughts until you know the athlete as a son or daughter. The key element in all of this is the fact that the coach athlete relationship is a shared experience and developing trust from the ground up is an essential component in knowing where your feet are at the beginning of that wonderful journey.

Teach them about the sport.

The biggest fear that I encounter with coaches is that they worry that they don’t know what they’re doing. They worry that if they try to teach something they will be found out. At the beginning it’s a realistic dilemma, but as you gain experience and knowledge, it is your job to share that knowledge with your athletes. There were many times in my career when I had to take the blame for teaching them something the wrong way. I’d explain where the new approach had come from, apologize for the fact that my limited experience at that time had seen things differently, and we’d all dive into absorbing the new approach to a skill or a tack in a new direction. Coaches worry that owning their mistakes undermines their credibility, but I see it as building credibility when you show your athletes that you can own your mistakes and grow from them. As their coach, it is your job to teach them everything you know about their sport. The beginnings of seasons or foundation development periods are perfect times to do that. Athletes who are exposed to repeated information take more and more on board each time and if you use those periods to question them at the same time, you will understand how much they have absorbed. This can be started at the developmental level and should be used as a tool to gauge their comprehension levels and create environments where they are asked to share what they know.

In the early stages of soccer practices, I have no problem asking a 10-year-old player to explain some aspect of the game they have been exposed to. As always in the initial stages they will struggle with their explanations, but with repeated opportunities they will get much better and organized in how they present their answers. The key is putting athletes or players in the spotlight to answer questions. It puts the athlete into environments where they begin to learn how to articulate what they see and understand. As their teammates watch them answer questions, you will find that they will focus a lot more on what’s being taught because they will want to make sure that they can answer the questions when “they” are put in that same spotlight. By continually giving them opportunities to show what they’ve learned, you will see the effectiveness of your teaching/coaching while at the same allowing them to develop a life skill.

Athletes who are taught the foundations of their sport will in time be able to share what they see about their sport form their point of view. In time their point of view will teach you more about the sport than any other source.

Allow them to take ownership over their career path.

To feel comfortable taking ownership over their sport, they need to understand the underlying physiology and mechanics of their sport. Ownership requires making decisions, and since it’s hard to make decisions about something you don’t understand, you need to teach them the foundations of technical side of performance. Since athletes are blessed with different shapes, limb lengths and sizes, they will eventually need to find their organic skills, and they can only do that if you teach them the foundations associated with any skill they might want to master. It takes a few seasons to seep in, but once they understand the cornerstone fundamentals, they can then explore all avenues available to them. By teaching them about the sport and to some degree the physiology behind the sport, they can take ownership of what they do and in time become a positive influence in helping how they evolve and prepare for competition. One of the biggest keys of ownership revolves around athlete feedback. As they learn and explore, spend more time asking questions to gauge where they are and what they’ve learned. This kind of interaction displays trust with your athlete and in my mind is an essential component to a strong respectful relationship. As you develop their understanding of the sport, make sure that some questions are open ended so that they continue to use critical thinking or cognitive flexibility to solve problems on their own time. Their ability to develop the skills to explore and understand their sport is a tool they can use in all phases of their lives, and when they realize success by expanding their flexibility in the athletic arena, they can translate that same level of problem-solving confidence into the human arena.

I was teaching a group how to harness kinetic energy when swimming freestyle. In the middle of the drills, I pulled them out of the water and asked them what wind turbines and swimming freestyle have in common? The question was followed by complete silence, so I asked them what a wind turbine was, what did it do? That prompted a good answer, and I used that to prompt them to figure out the correct answer. The key when following this kind of path is that there are no wrong answers or embarrassing answers. The coach should always respect any answer, and regardless of how off the track it might be, you have to ensure that they feel good about putting their thoughts on the line in front of their peers. Things like “good or great thought but it doesn’t work in this situation” helps them feel OK about answering the next time. In this situation I was using the context of how a wind turbine and swimming freestyle can both generate “free” energy. They climbed back in the pool with more understanding of how their arms could be like those turning wind blades and using that concept in freestyle could generate kinetic energy into the leveraging force. In addition, they were exposed to how cognitive flexibility might work for them. By using the example of how a wind turbine can relate to swimming freestyle they saw first-hand how knowledge from an unrelated area can shed light on solving a problem. As coaches we can’t expect our athletes to understand how to do this on their own, and it takes lessons like these to help them develop the ability for themselves.

When you create an environment that pushes your athletes to think and explore, it gives them ownership and a full share in their performance outcome. They become invested in what they do and by learning how to make decisions and articulating what they know to their coach, they grow as a person at the same time. As they become better at critical thinking and expand their cognitive flexibility they will begin to draw answers from many sources and in doing that, they will be well into the process of using sport as a steppingstone into a successful adult life.

Encourage them to explore.

Some sports require a combination of technical and tactical components that are played in a quantum environment, and some are simple linear expressions that are primarily technical with a light tactical flavor. Regardless, when the training environment is boring, athletes will switch off and their sportbrain will wander off into playing music or dealing with current social issues. Even when training environments are focused on team based or sprint-based events, if the training is repetitious or lacks stimulation, the athlete will still prefer to switch off and go somewhere else. Always keep the training stimulating and use creative training environments to help your athletes explore their environment. If you ask one athlete what they think or ask them if they’ve “discovered” something new, all of your athletes will begin thinking and exploring so that they are prepared when you ask “them.” This kind of interaction enhances the coach-athlete relationship, and the more you ask questions and get their answers, the more engaged they will be. If you make it a point to leave open ended questions on their mind, you will stimulate their search to come up with their own answers. Getting your athletes to develop their cognitive flexibility can only occur when the environment is a stimulating one, and part of the athlete development process should be centered around creating environments where they can do that.

Many years ago, one of my swimmers did an internship for a sport magazine and she decided to write an article on Freestyle. She framed the article as how she learned to swim the stroke from scratch as a freshman in college and illustrated all the steps she took and how each step impacted her learning process. My only involvement was a sit-down interview with her, and she did the rest on her own. The piece was so professionally written that coaches came up to me and complemented me on “my” article on freestyle. Hearing that led me to smile inside because I was immensely proud of her, and when I told her about those interactions, she reacted with a huge smile on her face and used that experience as a major self-belief booster going forward. It was a huge reward moment for her.

Later into my years as a coach I found myself coming up with interesting off the wall thoughts. They usually arrived in the middle of the night, and as I tell all coaches, always be prepared to record these thoughts regardless of when they arrive. In some cases, I would present a thought to my training group and ask them to explore the concept for the next 10 minutes. In most cases the thoughts wouldn’t gain any traction; in a few they would evolve into a usable drill and once in a while the exploration would follow a different track and an athlete would discover a new concept that produced a gem of a drill that could be used on a regular basis. When that happened, I named the new drill after the athlete who discovered it. When you name a new drill after an athlete, you’ll have every athlete in the program working hard to come up with the next drill that will hopefully be named after them. Everybody wins.

Teach them how to use intrinsic reward to enhance their self-belief.

If you ask a room full of young athletes or adults who their worst enemy is, you will get the same answer. They will all agree that it is themselves. Why is that, and why aren’t we all working extremely hard to combat that fact? As coaches it is our duty to help young people combat that enemy on a daily basis, and if you don’t make that one of your highest priorities as a coach, then you’re in the wrong business. Self-belief flourishes when you recognize or reward yourself for achieving something worthy or having done something new. The problem is that we’re more likely to dwell on all our deficiencies and negative and ignore those wonderful positives. When you master a new skill or simply help an older person at a grocery store, you must take the time to say WELL DONE to YOURSELF! That last step where you use intrinsic thoughts to pat yourself on the back must be done with an intense level of pride, and you have to feel that sense of awe or warmth in your “gut brain” when it happens. Athletes don’t do this readily on their own, and not only do coaches have to teach them the process of how to do that, they have to create training sessions where they can help the athlete learn how to use “their wins” as a development tool. I use the simple process of smiling at my athletes and patting myself on my back to let them know that I see them and I’m proud of them for their achievements. I use the action as a reminder to my athletes that they should be doing the same thing.

I’ve coached competitive soccer for many years, and rather than stopping the flow play during practice, I’d simply call out the athlete’s name and pat myself on my back. They’d know exactly what they’d been recognized for, and they could stay involved in the action. As they began to use the process effectively, I saw a significant uptick in their energy to play the game. Positive thinking is a wonderful tool when it’s pulled into the training environment, and everyone wins when you see those wonderful smiles as they enjoy that glow inside their gut after getting recognized for the way they executed a move, a skill or a challenge. If you’re walking away from a training session and you can’t recall one win from that training session, then you haven’t done your job as their coach.

Make them teachers.

It’s one thing to execute a skill and something completely different when you teach it. All teachers learn more when teaching, and by asking your athletes to teach other athletes, you will enhance their ability to see more of the game. It will give them a chance to improve their cognitive flexibility as they look for the right words or examples to articulate and illustrate what they see and feel. Once I’ve taught my athletes the foundations of every skill, I TRUST them to be able to teach that skill to their teammates. I’ve been in the coaching business for over forty years, but I still believe that athletes do a better job of relating things to each other than you do with them. Often sharing how they solved the initial challenge is far more illuminating to a teammate than any descriptive vocabulary I might use when I introduce a new concept to them.

Many years ago, I had an athlete who was naturally gifted out of the starting blocks. During a session on starts I asked him to explain to the group how he executed his start. I hadn’t given him a heads up with regards to putting him on the spot, so all I got was a scrunched brow and a blank face. His eventual answer was… “I don’t know how to explain it, I just do it.” As your experience grows as a coach you will run into a plethora of gifted athletes who can execute skills with zero understanding of how they do them. It will just happen for them. The Pandora’s Box question is, do we illuminate it for them, or just leave well enough alone. In my mind helping them see and understand their natural gifts is an essential component to helping them find the next level, so I take the time teach all my athletes regardless of how talented they at a skill. In this case, after a period of learning he began to fully understand the dynamic and in time became a one of my best teachers. In time he was also able to improve his skill and was almost unbeatable in the first 15 meters of any race.

A few years ago, I was teaching the “tumble pop” turning skill to a new group of swimmers. A few lessons into their adaptation process a new athlete was added to the equation. Rather than taking the time to start from scratch I trusted an athlete in the group to take the new athlete into a different space and teach her the basics. They went off on their own and I never paid them any attention until they came back to the group 20 minutes later. I stopped what we were doing and asked the new swimmer to show us what she’d learned. As she approached the wall her teacher, with the look of an expectant mother watching her child, craned her neck above the surface to see if she did it well. She was spot on, and not only did I reward the skill execution, but I smiled at the teacher and patted myself on my back to let her know how well she’d done. Teaching helps athletes understand more about the subtleties associated with the sport specific skills, helps them take a stronger interest in the sport in general, and helps them become more invested in their team and the outcome of the team. When you allow your athletes to become teachers you tell them that you trust them, and that trust is another major building block in the relationship between an athlete and a coach.

Connect sport to real life.

Sport is this amazing opportunity where we can immerse ourselves into a non-threatening environment and learn how to cope with real life situations. That only happens if the teacher is willing to help connect the dots for the athlete so that lessons learned in training or in competition are absorbed as real-life learning experiences. I’ve always said to my athletes that if they’re not failing on a regular basis, they’re not working hard enough. Failure is the best teacher in the world, and in my mind the more lessons you learn the more robust that “sportbrain” of yours will become. There is no end of opportunities in the coaching world where athletes can be told… “look at how well you managed that, and one day you will be able to wow a boardroom using that same technique.” Wins and failures are part of the fabric of their physical and emotional development, and it is your job as their coach to relate how those teaching moments will help them get better as an athlete and in time give them the confidence to live a strong and meaningful life.

Encourage them to become innovators.

The athletes mind or “bodybrain” knows more about themselves than any coach can ever know, and as you get to know them, allow yourself to trust their sense of where they are. Trusting their instincts is an important step in your relationship with them and as their “sportbrain” expands its capacity, encourage them to think outside the box and develop new ideas, concepts, or drills. More importantly than that, you want each individual athlete thinking hard about what works best for them as an athlete. If the goal is to achieve their “organic” potential, then getting out of the mainstream and thinking for themselves is a critical step to being successful as an athlete.

When I was exploring the concept of Hydro Freestyle, one of my athletes played a huge role in how that stroke was developed. He was at competition on his own, saw Finis alignment kickboard and started playing around with it. In the process he had a huge “aha moment.” The net result of his exploration with a new tool at that meet resulted in the main drill I use to teach “hydro” freestyle. If you teach your athletes the foundations of the sport, give them the license to teach the sport, they will in time teach you more about the sport than anyone else in the sport. The is no question that I have learned more from my athletes than any other source, and by encouraging and trusting them as innovators, you increase the wealth of your institutional knowledge, and you add another layer to your relationship with athlete as their mentor and coach.

Encourage them to become collaborators.

When athletes become fully vested in the teaching side of the sport, they become knowledgeable enough to make recommendations with regards to their adaptation side. Even before they become teachers, I give them full responsibility with regards to how they prepare for competition, so collaborating on the adaptation/development side is simply an extension of that process. It should be noted that this is the peak of the athlete/coach relationship and occurs at the elite level, but everything prior to this is part of that steppingstone process. It just doesn’t happen automatically when the athlete becomes a professional, it happens because you’ve both put in years of talking, teaching, and sharing everything you know and feel about the sport you love and respect.

How this is developed at the Age group level.

Everything about this level should be immersed in “fun and adventure.” Their development process should follow simple sequences that are designed as much for entertainment as training. Teach them how to feel comfortable when immersing themselves in the water; teach them how to float and balance in the water; teach them how to kick and manage their shape in the water; teach them how to develop a body-based harmonic in the water, and finally introduce the full swimming strokes to them. This period should be a lot less about competition and a lot more about learning while exploring a sport. As they follow that basic development structure, get to know basic things about them. Simple likes and dislikes, pets, colors etc. Stuff that helps them feel that you know them. Athletes at this age should be taught the basics of the reward system; they should be encouraged to explore and think for themselves, and they should be recognized when showing ANY level of improvement. Things like using them as a demonstrator or allowing them to pick a skill or a game to play is a huge steppingstone to helping them feel value in what they are doing, and more than that, that you care about them as a person.

I was working with a 6-year-old golfer on the driving range. To help him I got down on my knees and helped him get his feet placed the right way. As I watched him struggle to hit the ball, I continued to give him physical and mental cues on how to do that. He was all concentration, and we celebrated the two times he connected very well. Big smiles all around. When the buzzer went off for the players to change stations, I stood up to see where he needed to go. As I was looking around, I felt his hands brushing all the grass and dirt off my knees. I looked down, and there was this beaming smile as he did that. I ruffled his hair as I thanked him and sent him on his way to the putting station. Young children are very trusting of adults and as coaches we can’t simply take that trust and use it without showing that you actually care. By going down to his level and getting my knees all grungy, I showed him that I was willing to get dirty to help him figure it out. Because we were almost eye to when he was successful, our smiles connected a lot more and he showed that connection with and act kindness of his own.

How this is continued at the teenage level.

At this level the athletes begin to see the world around them. They start out thinking they are going to take the world by storm and as they open their eyes, reality sets in. Helping them find value in who they are and what they are doing is vital with regards to staying involved in a sport. Because they now have a much clearer picture of where they fit, it’s your job to help them find a sense of meaning regardless of where they fall inside the performance spectrum. As a species, we are extremely competitive by nature, so as their coach you not only have to create a strong bond with every swimmer in the group, you have to help them love who they are, and what they are doing. Sport shouldn’t be as much about winning as it should be about improving and getting better and through that process understanding how a team-based environment helps everyone understand the differences between each other. They should be cultivated to recognize and respect the fruits of their labors and during this period your relationship with the athlete will help them understand how what they learn while training for competition will help them become very productive as a human being. Your person inside the athlete discussions should have more depth to them, and at this stage they should be able to formulate a “why” as a person, and a “why” as an athlete. They should be taught how and why the reward system works; be taught about the technical side of the sport; begin to be used as teachers within the team to help them find value and be given a much higher level of responsibility as to their performance and outcome. Athletes regardless of their level in the spectrum, will stay in a sport if they fall in love with the value they get from their sport. As their coach, your relationship with them, will be a key element with regards to whether they continue or quit entirely. Regardless of their ability level, they should be taught that their performances in competition will never define them as human beings and that sport should always be a fun activity where they can put their commitment and training on the line.

I coach a U11 girls soccer team and getting to know younger athletes is just as important as older more mature players. The girls were into the game, and I was on the sideline helping them explore the game. I had one player on the bench who wasn’t very interested in soccer and instead of watching the game she was off doing her own thing back in the bench area. Early on into the game I felt this bump on my leg. I looked down and there was this player showing me a ball of grass that was perched on top of the flat of her hand. She looked up at me and said: “It looks like a brain, doesn’t it?” I dropped to my knees, and we had this amazing conversation about how cool it was that she could see a ball of grass as a brain, and that she was really gifted to be able to do that. For about 3 minutes, the game went on in the background as we had this conversation about academics and the fact that she really didn’t like soccer but played it because her mom made her go to practice. It was a wonderful moment with this young person, and it helped her see that I didn’t judge her because she didn’t like soccer or struggled to play the game, but I judged her on how she was able to share and communicate with me.

Many years ago, I had a freshman athlete who struggled at the championship meet. Her adaptation journey was a rocky one and it took me months to gain her trust. Because I expect my athletes to take ownership and learn through an experiential format, she struggled with her confidence at the beginning of the meet, and it took her till the last day to smile after a race. As a personal development exercise, the following week I asked her to research words associated with being confident. Every day she would give me the word she was going to research, and then at the end of the day she would share what she’d learnt. The words she chose were words like Trust, Courage, Belief etc.

The one she researched that impacted me the most, was Belief. In sharing her thoughts with me she said that belief could mean many things, but the thing that really struck her, was the simple statement that “there is no thinking in belief.” It was a simple profound observation that struck me as being very insightful, and right then and there, I asked her if I could use her words going forward. I have used the statement “there is no thinking in belief” many times since that day, and believe that it’s interactions like that, that are the true fabric of helping young people become dynamic athletes and confident human beings. She’d been out in the work force for a few years when I had lunch with her, and we talked for about 4 hours. It was a wonderful nostalgic moment with a former athlete, and although she ended her career as an Academic All American, my true pride as a coach lay in the fact that she’d started college as a hot mess and ended up being this wonderful human being. Too me, that is what being a coach is all about.

We start out as young coaches thinking that performance and outcome are the most important things because we can bask in the glow of the athlete’s glory. It’s very easy for coaches to fall into that trap because if the athletes don’t perform, they feel like they haven’t done their job. It all goes back to the assertion I started with; coaching is less about the physical training and more about the way we communicate with our athletes. There is no question that all of this cannot occur without the physical development side, but if coaches cannot see and understand the importance of the holistic side, then opportunities will be lost. The key component of all those presented is the understanding that when someone does something new, or succeeds in a challenge, we have to support their success as both a trainer and a coach. Athletes must be taught how to think strong internal emotional thoughts that reinforce the fact that they’re physically better or stronger, while at the same time they should always follow those thoughts with strong internal thoughts saying “I'm an AWESOME person” for doing/achieving that. The first REWARD based affirmation addresses the physical brain, the second addresses the cognitive thinking mind. The combination of the two is the key. When you align success in training with positive self-talk, you increase the potential for success and coaches should be mindful of looking for every opportunity to coach the person when those win opportunities occur. More than that, every training session should be based on creating “wins” during training so that the coach can coach the person inside the athlete. Regardless of their potential as an athlete, focusing on the holistic side of their development should be our primary focus and by developing a strong athlete/coach relationship we will be helping a young person develop the strength and confidence to face anything in their path.