Concussion

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Concussion Awareness Day 2022

Quite unintentionally, I found myself this morning at breakfast reciting the following nursery rhyme with my granddaughter:

It’s raining, it’s pouring

The old man is snoring

Bumped his head

And he went to bed

Couldn’t get up in the morning.

The act of bumping one’s head is so common that many times, we fail to consider the spectrum of outcomes from such an event. While most impacts are innocuous for most people most of the time, for some people some of the time, the same degree of impact can result in a devastating change in destiny. The underlying reasons for the variability in outcomes continue to vex researchers and clinicians.

So, what is a concussion?

The most basic definition of concussion is any alteration in neurologic functioning that occurs following either direct impact to the head (aka blunt force trauma) or acceleration-deceleration forces transmitted into brain tissue (as in whiplash).

When these unexpected forces are inflicted on the brain tissue, the actual shape of the tissue is distorted, much like a gelatin mold being shaken. This gelatin, however, contains thousands of small wirelike connections (axons) that carry signals from one part of the brain to another and that movement stretches some and may even tear some, causing some degree of disconnection between the regions of the brain.

While typically the change is seen soon after the event, on occasion the change may be delayed. The areas that are involved determine the type of symptoms observed.

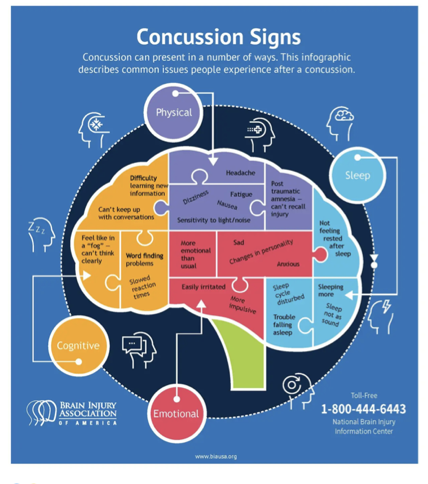

The nature of these alterations is illustrated in the following graphic from the Brain Injury Association of America:

Virtually any neurologic function can be altered after a concussion, most commonly temporarily. The more insidious changes tend to be those relating to behavior, especially when these occur in children and adolescents where behavioral fluctuations (irritability, crying, agitation) can be age or developmentally prevalent. The presence of “hard” neurologic changes (loss of consciousness, initial seizure, the emergence of a primitive reflex, asymmetric reflexes, eye movement abnormalities, etc) makes it easier to recognize the occurrence of a concussion. Unfortunately, these markers aren’t typically obvious or present. Using standard tools such as the Glasgow Coma Scale frequently misses concussion as this scale was originally designed to assess COMA, and not concussions. More specific instruments such as the SCAT (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool) or ACE (Acute Concussion Evaluation) provide better yield but are less frequently employed by ERs or First Responders.

What occurs then is an underreporting of concussions by ERs, which has been described in several research studies. Despite this, the overall annual number of concussions tabulated by the CDC has been increasing over the past several years, possibly owing to increased public awareness and their persistence in seeking appropriate identification and care. A recent National Academy of Sciences review of the system of care needs for traumatic brain injuries (of which concussion represents the mild end of the spectrum) found a lack of effective follow-up services once these injuries were identified. Research studies have demonstrated that early intervention regarding symptom management, understanding of the course of recovery, instruction on optimizing sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hydration, and management of any behavioral symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or self-medication with substances of abuse prevents later complications and facilitates recovery of function. The epitome of this system of care is seen in our professional sports teams, whose overall interests are best served by providing these necessary services rapidly and efficiently to ensure a timely return to play. For the rest of the population, this type of integrated care is not commonly available, especially when financial resources are limited or non-existent.

The human brain develops from conception to the mid-twenties, with the period in the teens and beyond centering on the development of frontal lobe systems critical for ultimate adult roles such as emancipation from parents, self-motivated productivity, societal navigation, and establishment of a successful adult intimate relationship. Concussive injuries, especially repetitive events, disproportionately impact these frontal lobe functions, creating future vulnerabilities. While concern over the development of the concussion-specific dementia CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) merits attention, impairments to the frontal lobe such as these are more typically observed as obstacles to successful life progression in this clinician's four decades of experience. Without question, more immature brains (those younger than 14) should not be engaged in contact sports where the risk of head impacts exists. Even repetitive subconcussive impacts have potential cumulative consequences. Limitations on full-contact practices after age 14 to reduce the total head impact burden offer another solution.

When the inevitable concussive injury does occur to the student-athlete, it is critical to focus on the fact that the STUDENT comes first. He/she/they are not an athlete first. They are developing children/adolescents whose brain requires careful management to prevent long-term consequences. It is not necessary to employ the following treatment:

However, all the adults involved should be supportive of the “student first” concept in the recovery plan. The student must be encouraged to heal completely before being re-exposed to the potential of a subsequent concussion.

What is the outcome of a concussion? While NCAA studies have found resolution from sports-related concussion essentially by 6 weeks, frequently more rapidly, other studies across the age continuum show over 50% still find differences in their abilities 12 months after a concussion. Pre-existing factors such as prior concussions or neurologic disorders, psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, substance use), female gender, age over 40, and chronic medical illnesses are associated with persistent symptoms or incomplete recovery.

How this event impacts one’s life is a complex interaction of biological/genetic vulnerability, psychological resilience, social support/flexibility, and environmental resource availability, which offers multiple points for intervention.

In the end, however, prevention is the only absolute cure.