Baseball

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Baseball Athletic Test: A Baseball-Specific Test Battery

Elite baseball players recognize that championship performance rarely occurs by chance but is the product of consistent and effective training. This “excellence does not occur by accident” philosophy can be utilized by strength and conditioning professionals to measure and evaluate physiological, athletic, and sport-specific skills that can be predictors of successful baseball performance (2,3,10,12,14,15,17-25). Test results can then be used to prescribe training programs designed to meet the specific needs of individual athletes. Subsequently, identifying a battery of tests and testing protocols that evaluate these key performance components can be useful for coaches and strength and conditioning professionals.

The purpose of this article is to introduce the baseball athletic test (BAT), a battery of tests designed to evaluate player's strengths and weaknesses. Specifically, special attention will be focused on the sport-specific portion of the BAT, which includes throwing velocity, bat speed, and batted-ball velocity. Although space limitations do not permit the inclusion of test protocols in this article, detailed test instructions can be found in a variety of sources (1,5-7,9,25). The complete BAT includes the following battery of physiological, athletic, and sport-specific tests. The following tables include a summary of normative data contained in references 5, 15, 17, 19, and 21.

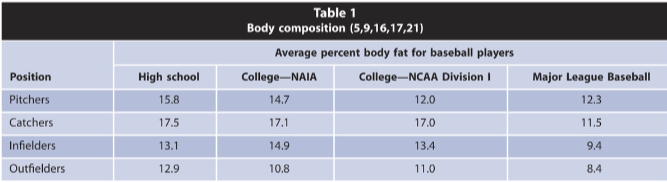

Body composition

Percent body fat and lean body mass are typically assessed by skinfold calipers, bioelectrical impedance, hydrostatic weighing, or dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (8). Appropriate body composition is important for successful baseball performance, especially in the areas of fielding and baserunning (5,13,16). Also, body weight and lean body mass appear to have a high positive correlation with bat speed and batted-ball velocity (2,12,19,22-24) (Table 1).

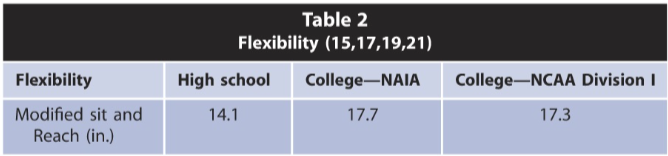

Flexibility

Appropriate flexibility is fundamental to enhancing injury prevention and maintaining athletic performance. It is typically assessed by the modified sit and reach, shoulder rotation, and/or total body rotation tests (5-7) (Table 2).

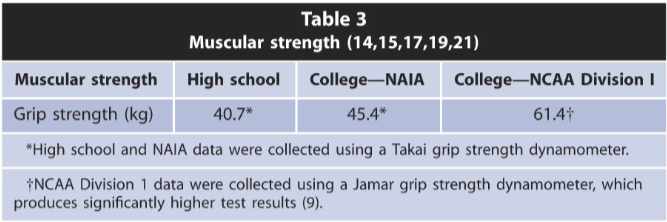

Muscular strength

Due to the anaerobic nature of the game, muscular strength plays a significant part in baseball performance (3,15,18,19). Many static and dynamic tests can be used to measure muscular strength. It is strongly suggested that one such test, grip strength, be included in the assessment process because research suggests a positive relationship between grip strength and throwing velocity, bat speed, and batted-ball velocity (2,3,14,15,18,19,23,24) (Table 3).

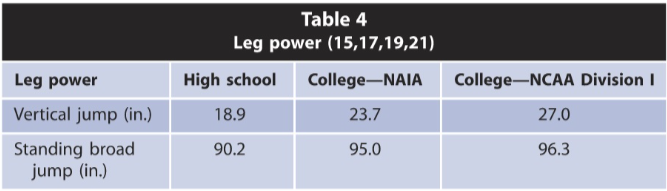

Leg power

Power production is important for baseball success. Hitting, running, and throwing all require a summation of forceful movements generated from the ground up. Common field tests for leg power include the vertical jump and standing broad jump. Leg power has been shown to have a positive relationship with throwing velocity, bat speed, and batted-ball velocity (3,12,15,19,22,24) (Table 4).

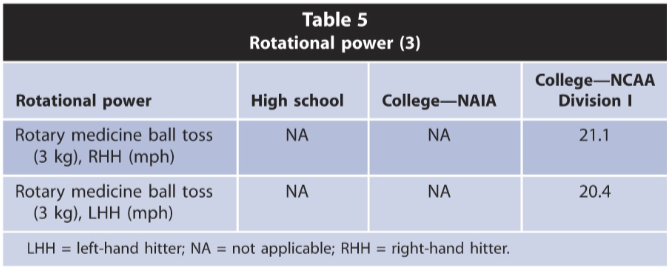

Rotational power

Rotational power plays a special role in baseball performance, especially because throwing and hitting skills utilize a transverse plane of motion. The BAT utilizes the rotary medicine ball toss with a 3-kg medicine ball and is measured by a radar gun in miles per hour (mph) (3). Rotational power has been shown to have a positive relationship with throwing velocity, bat speed, and batted-ball velocity (3,23) (Table 5).

Agility

All players and positions require agility to achieve baseball success. However, infielders and outfielders probably have the greatest need for rapid changes of direction. Depending on the player's maturity level, the T-test, shuttle run, and pro agility test (5-10-5) are valid tests that can be used to assess agility (6) (Table 6).

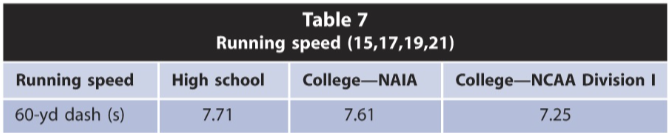

Running speed

Speed plays a significant role in many aspects of the game of baseball. The 60-yd dash is a popular speed test that has been used in baseball for many years. However, other speed tests can be used as well (e.g., 30-yd dash, home to first, home to second, etc.) (5). On average, middle infielders and center fielders are the fastest players, whereas catchers tend to be the slowest (5) (Table 7).

SPORT-SPECIFIC TESTS

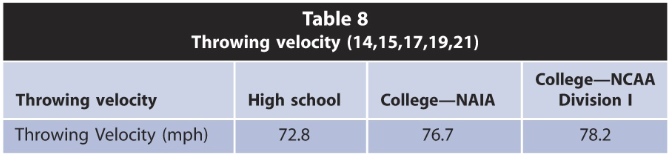

Throwing velocity

Arm strength is a highly regarded baseball skill that is essential to all positions. Many protocols are used to measure throwing velocity (game situations, throwing from positions, etc.); however, all utilize a radar gun to record speed in mph. The BAT utilizes a standardized throwing protocol, which requires the player to make 5 maximum throws with a regulation 5 oz baseball on flat ground from the pitcher's stretch position. No shuffle, crow hop, or running start is allowed. The distance the ball is thrown is irrelevant because the radar gun measures ball velocity immediately on release from the player's hand. The maximum throwing velocity is recorded in mph. Research indicates a positive relationship between throwing velocity and lean body mass, grip strength, and leg power (14,15) (Table 8).

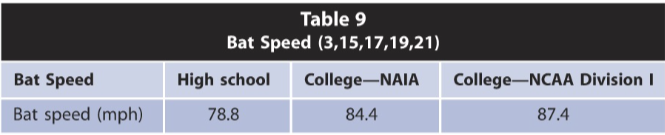

Bat speed

Another highly regarded baseball assessment, bat speed, is directly related to hitting success (4,11,20). Typical devices for measuring bat speed include chronographs (ATEC Sport Speed Trainer 2000), Doppler radar (Swing Speed Radar), and lasers (BattMaxx 5500). The BAT utilizes a standardized bat speed protocol, which requires the player to use their game bat to hit 5 line drives off a batting tee into a net. The player's maximum bat speed is recorded in mph by the ATEC Sport Speed Trainer 2000. Research indicates a positive relationship between bat speed and body weight, lean body mass, grip strength, upper-body strength, lower-body strength, leg power, rotational power, and angular hip velocity (2,3,12,15,18,19,22-24) (Table 9).

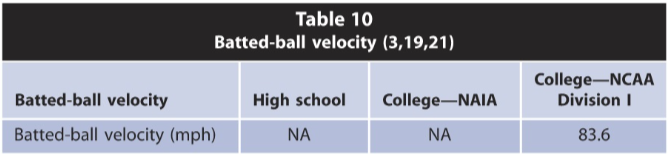

Batted-ball velocity

The BAT simultaneously measures batted-ball velocity with a radar gun while measuring bat speed. After each swing, the test administrator should record the player's bat speed and batted-ball velocity in mph. Players should train to maximize bat speed and to generate batted-ball velocity that is equal to or greater than their bat speed. Research indicates a positive relationship between batted-ball velocity and body weight, lean body mass, grip strength, leg power, and rotational power (3,15,18,19,24) (Table 10).

If utilized properly, the BAT can provide valuable information to assist the strength and conditioning professional in designing effective training programs for baseball players. Test results can be compared with normative data to determine the strengths and weaknesses of individual players. Subsequently, training programs can be designed to improve deficiencies, which may lead to improved baseball performance. In addition, the BAT can be utilized as a talent identification battery when recruiting and scouting combine.

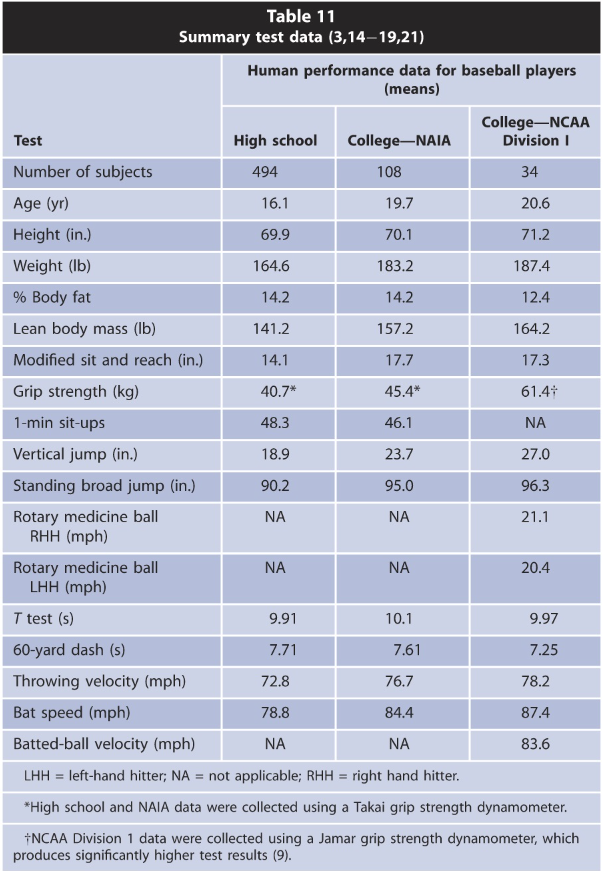

The following table includes a summary of mean (average) test scores for the BAT. The means are divided into high school, NAIA, and NCAA Division I categories and can be used for general comparison purposes (Table 11).

Although testing certainly requires an investment of time, effort, and equipment, the reward is that better information = better decisions = better performance. And ultimately, improving performance is what testing and strength and conditioning is all about.

REFERENCES

1. Barr C, Bellow J, Reilly L, and DeMello J. Relationship of physical characteristics and various strength measures to bat velocity. J Strength Cond Res 19(4): e4, 2005.

2. Basile R, Otto RM, and Wygand WJ. The relationship between physical and physiological performance measures and baseball performance measures. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: S214, 2007.

3. Bonnette R, Spaniol F, Melrose D, Ocker L, Paluseo J, and Szymanski D. The relationship between rotational power, bat speed, and batted-ball velocity of NCAA Division I baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 22(6): e112, 2008.

4. Breen JL. What makes a good hitter? JOHPER 38: 36-39, 1967.

5. Coleman AE. 52-Week Baseball Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000. pp. ix-xx.

6. Harman E and Garhammer J. Administration, scoring, and interpretation of selected tests. In: Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning: National Strength and Conditioning Association. Baechle TR and Earle RW, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2008. pp. 249-292.

7. Heyward VH. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2002. pp. 227-246.

8. Heyward VH and Wagner DR. Applied Body Composition Assessment. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2004. pp. 27-45.

9. Hoffman J. Physiological Aspects of Sport Training and Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2002. pp. 169-184.

10. Kohmura Y, Aoki K, Yoshigi H, Sakuraba K, and Yanagiya T. Development of a baseball-specific battery of tests and a testing protocol for college baseball players. J Strength Cond Res22: 1051-1058, 2008.

11. Race DE. A cinematographic and mechanical analysis of the external movements involved in hitting a baseball effectively. Res Q 32: 394-404, 1961.

12. Reed JG, Szymanski DJ, Albert JM, Hawthorne LZ, Hemperley DL, Hsu HS, Skinner CJ, and Tatum JR. Relationship between physiological performance variables and baseball/softball specific variables of novice college students. J Strength Cond Res 21(4): 111-112, 2008.

13. Signorile JF and Kluckhulm K. Assessment and training in baseball. In: Isokinetics in Human Performance. Brown LE, ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000. pp. 378-406.

14. Spaniol FJ. Predicting throwing velocity in college baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 11: 286, 1997.

15. Spaniol FJ. Physiological predictors of bat speed and throwing velocity in adolescent baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 16(4): 6, 2002.

16. Spaniol FJ. Body composition and baseball performance. NSCA Perform Train J 4: 10-11, 2005.

17. Spaniol FJ. Physiological characteristics of NAIA intercollegiate baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 21(4): e25, 2007.

18. Spaniol FJ, Bonnette R, and Melrose D. The relationship between grip strength and bat speed of adolescent baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 21(4): e19, 2007.

19. Spaniol FJ, Bonnette R, Melrose D, and Bohling M. Physiological predictors of bat speed and batted-ball velocity in NCAA Division I baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 20(4): e25, 2006.

20. Spaniol FJ, Bonnette R, and Paluseo J. The relationship between batted-ball velocity and batting performance of NCAA Division I baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 22(6): e83, 2008.

21. Spaniol FJ, Melrose D, Bohling M, and Bonnette R. Physiological characteristics of NCAA Division I baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 19(4): e34, 2005.

22. Szymanski DJ, Albert JM, Reed JG, and Szymanski JM. Physiological predictors of sport-specific skills of Division I collegiate baseball players. SEACSM Abstracts. Birmingham, AL, February 14-16, 2008. pp. 27.

23. Szymanski DJ, Szymanski JM, Schade RL, and Bradford TJ. Relationship between physiological variables and linear bat swing velocity of high school baseball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40: S422, 2008.

24. Szymanski JM, Szymanski DJ, Albert JM, Hemperley DL, Hsu HS, Moore RM, Potts JD, Reed JG, Turner JE, Walker JP, and Winstead RC. Relationship between physiological characteristics and baseball-specific variables of high school baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 22(6): e110, 2008.

25. Watkinson J. Performance testing for baseball. Strength Cond J 20(4): 16-20, 1998.