Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Third Class Levers and The Weightlifting Body

In my last article, I shared a table of guidelines for the relationship between a weightlifter’s height and bodyweight class. It should be evident to most athletes, fans, and coaches that two athletes of the same bodyweight but rather disparate heights will not be able to lift the same weights. For example, if two lifters both weigh 60 kg, but one is 1.6 m, and the other is 1.8 m in height, and all other factors are equal, the shorter athlete will be able to lift heavier weights.

Understanding the Science

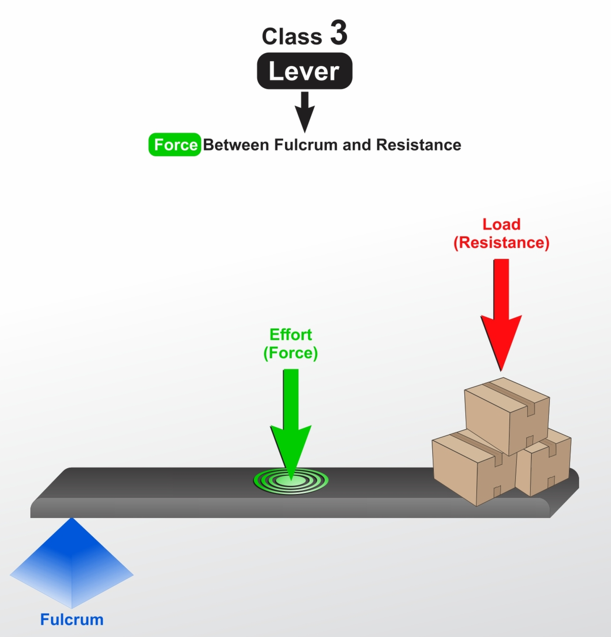

What I’ll try to do here is explain the science behind this. A third-class lever is diagrammed as follows:

A third-class lever always operates at a mechanical disadvantage, meaning it requires more effort (force) to move a load than the weight of the load itself. This is because the effort is applied closer to the fulcrum (pivot point) than the load is.

In simpler terms, if you have a lever where the distance from your hand (effort) to the pivot is shorter than from the pivot to the weight you’re lifting (load), you must exert more force to lift that weight.

Moreover, the longer the lever (the distance from the pivot to the load), the more force you need to apply to move the same weight.

Levers in the Human Body

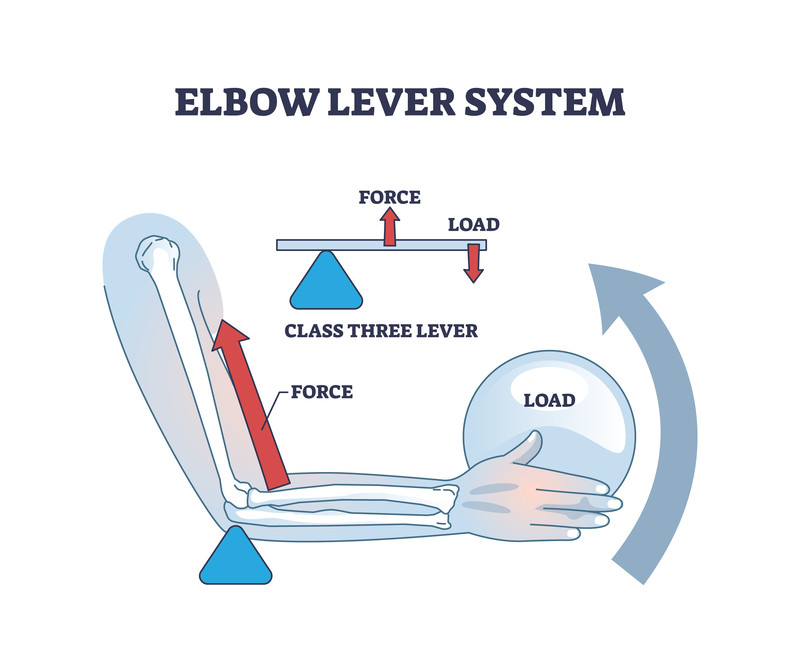

The joints at the shoulders, knees, hips, and elbows are third-class levers. The lever at the elbow is depicted here. The E represents effort, which is the same as force.

For example, lifting a weight with a long arm (lever) is harder than lifting it with a short arm because the longer lever increases the distance over which the force must be applied.

This is why taller athletes who have longer limbs need to generate more force to lift the same weight compared to shorter athletes. Their longer limbs act as longer levers, making it more challenging to lift heavy weights.

Progress and Muscle Mass

Most lifters start out by making progress once technique has been mastered. These novices must realize that there is a limit to how much progress can be made without increasing muscle mass, which becomes the only way to increase force. Less experienced coaches may also not be aware of the eventual need to increase muscle mass.

Long-Term Goals for Lifters

The long-term goal for both groups should be for the lifter to become the best weightlifter possible. While the initial results might find a talented but lanky lifter outperforming shorter, less talented competitors at the local level, for success to translate to the national or international level, muscular bodyweight will have to increase.

Real-Life Examples

I’d coached a few New Yorkers in my career, and they recognized when a lifter could no longer make progress at a given bodyweight. They called it “played out,” as in “He was played out at 77 kg. He needs to blow up!”

Guidelines for Progress

So, the table I posted in this article represents guideposts to help lifters get to the height/bodyweight ranges where the greatest progress will be made. I expect that there will be some reluctance and exceptions will be pointed out, but exceptions are not justifications for deviating from well-established norms. My only advice for those willing to add muscular bodyweight is not to rush the process, but to gain the muscle mass at a rate that allows the other systems of the body to accommodate the change.