Strength And Conditioning

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

NFL Combine

With the NFL combine and draft coming up, I will dive into the problems with the combine and the proper use of testing especially for player selection. At the end, I will connect this to coaches in other sports and other levels.

For American football fans, the NFL Combine has become an EVENT that is (in non-COVID years) televised and followed closely. The idea for the combine goes back decades when film of players and other information was not as readily available, and maybe not so reliable; many of the best players are invited to one place where all the teams could gather and measure them for height and weight and meet the players. Assessments thought to be predictive of future performance were included. Think of it as a massive job fair for very athletic people.

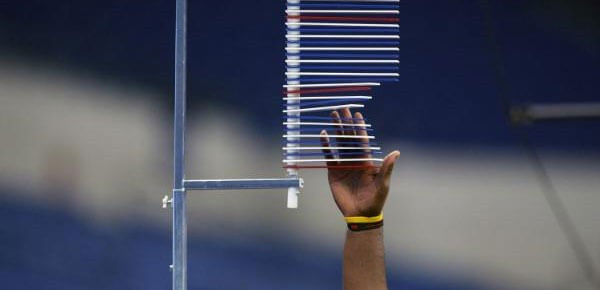

For those lucky enough not to be exposed to the “underwear Olympics”, as it is sometimes called, the activities include the 40-yard (just shy of 40 meters) dash and the 225-pound bench press (a little over 100 kilograms). These are two activities that have bothered me for a while. As someone trained in the sports sciences, I look at these and question the validity of the assessments. For instance, football players rarely run 40 continuous yards in a straight line from a crouched start. While receivers and running backs may often do this, quarterbacks rarely do and linemen even more rarely. So why measure something so few do? To the credit of the evaluators, they now collect the splits for the 40 so that they have the first 10 yards, a measure that seems much more applicable to what football players do in their job.

The bench press is another assessment that is problematic. The challenge here is to do as many repetitions as possible with 225 pounds on the bar. First, why 225? Second, what is being measured here? It is muscular endurance, not strength or power (the ability to exert force quickly). A play in football lasts a few seconds from snap of the ball to the whistle so endurance per se is not a key attribute you want in your football players. The bench press is also done in a position that no football player wants to find himself in—flat on his back. Lastly, the bench press favors players with shorter arms (less distance to move the bar) and yet it is preferable for a football player to be “long” that is have a large wingspan.

Another issue is that players (or their agents) spend a lot of money going to sites to train for the combine. Speed coaches teach them the skills needed to shine at the combine like how to get a better start in the 40 or do better in the change of direction cone drill. Improving one’s 40-yard dash time by 0.1 seconds likely means moving up in the draft and that means more money for the player.

Now that the combine has been around for several decades, researchers have looked at how well the combine predicts NFL performance. It should be noted that many “combine gods” who wowed NFL draft personnel failed spectacularly and players who wowed no one went on to amazing NFL careers including, arguably, the greatest NFL quarterback of all-time who was famously drafted after 198 other players that year. But anecdote is not the singular of data.

The data is mixed and nuanced. Several studies looking at correlations between NFL combine performance and on field performance have found little predictive ability. On field performance is measured in many ways (games played, plays played, accolades such as all-star selections, etc.). In some cases, some tests seem to do a decent job of predicting on field performance in some positions as shown in some studies. For instance, the standing long jump is an excellent field test for explosive power---a desirable quality in American football and perhaps should carry more weight. (The sport scientist in me says “Add a force plate to get even better data”).

Another issue is that the talent gap of those roughly 300 players invited to the combine is very narrow already. It is like the gap in times at the Olympic 100-meter dash is much narrower than at high school or all-comers meet. Essentially the bests are being invited so the ability levels are very narrow and drawing distinctions can be very difficult when talking about translating these results into predicting performance in a complex game such as football. Is a player who runs a 4.32 40-yard dash that much better than a player who runs a 4.38?

I believe in the saying “the best predictor of future performance is past performance”. As one paper notes. If you are evaluating players for selection, watch what they do in actual competition. Some people who are very athletic do not perform under game conditions and pressures; some people do not take testing very seriously or are new to it. In many sport science studies, habituation trials are included to get the athlete used to the procedure and equipment. For instance, measuring the running ability using a treadmill on a distance runner who has never run on a treadmill can be problematic as the unfamiliarity creates a confounding condition.

Now for coaches at other levels…testing athletes is a common thing, for instance in basketball the vertical jump is probably the best-known measure. Too often I have seen coaches of youth athletes line everyone up and do vertical jump tests as a one-off test.

Is this the best use of this assessment? Could it do harm?

First, one-off tests often tell you what you already know. Ask a basketball or volleyball coach who the best leapers are, and they can tell you. A better use for this test would be to measure vertical jump and then work with the players to improve it; measure it again later to see if the intervention worked.

Along those lines I would recommend not sharing the results with other members of the team. This does not mean that players will not share, but that should also be cautioned against as explained below. Focus on how each player can improve on the baseline results. Vertical jump can be increased, but, as with many traits, a lot of one’s ability to jump high is innate and each athlete has a ceiling---the trick is to optimize that ceiling!

Another aspect on sharing data is for youth athletes who are already comparing themselves to one another and figuring out how they “measure up”. For young athletes, this sort of comparison from the coach could feed into that sense of not measuring up and lead them to drop out of the sport. Those players might often be younger and less physically mature than their peers. For example, a player born in January of 2011 could be playing alongside a player born in December 2011; they are both playing U12, but the player born in January is almost a full year older. At some ages that 11 months is a huge difference.

Testing can be useful when properly used and interpreted. It needs to be chosen carefully and to be measures that are applicable to the sport. Caution should be taken in terms of using testing to predict performance or who should be chosen for a team as Tom Brady would testify.

References and more readings