Volleyball

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

How do you pass a volleyball?

Passing requires the ability to read and predict the serves' trajectory and the player's ability to understand and be aware of his/her own space.

In my book the 21st Century Volleyball Expertise, I lay out all of the sequences of practices below. I would like to elicit the concept of “passing with expertise in mind.”

In a coaches' clinic in Colorado, Dr. Doug Beal and Dr. Bill Neville shared that it is hard to find good passers because they need to know how to position themselves and discern the midline of the ball path's midline.

Passers also need to have the patience not to react to the variations and floatations of the ball. For that reason, in the 80's it was hard to find four good passers which forced the coaching staff to specialize and rely on the passing role to Kiraly, Powers, Bob Ctvrlik, and the defense specialist Sato.

To learn how to position on the court, players need to recognize the passing zones and explore their spaces through quick runs back and forth in the low ready position and then move using the shuffle footwork pattern, always moving in zig-zag close to 45 degrees angles.

In addition, to "be there, relaxed and cool, the passer must rehearse the multiple possibilities of moving to the ball in a quick reaction. In the Science of Volleyball, Dr. Karl McGown explains that the passer must be ready to move into the eight directions but use multiple patterns.

I have personally used this method of training without the ball by mimicking the quick feet moving forward, dropping the quick feet going backward, using the shuffle with a big first lunge step to the right and the left, moving diagonally forward to the right and the left and finally, dropping diagonally back to the right and the left, and immediately, angling the platform to the target.

Dr. Platonov adds that when the serve is a couple of feet away from the passer midline, it is important to look at the target at the moment of contact so all connector muscles will follow the eyes, thus guiding the ball to the desired zone. Although many coaches call this fine movement "intuitive", I have studied that this application of the high-level passing technique is an application of eye-hand coordination, thus it makes perfect sense.

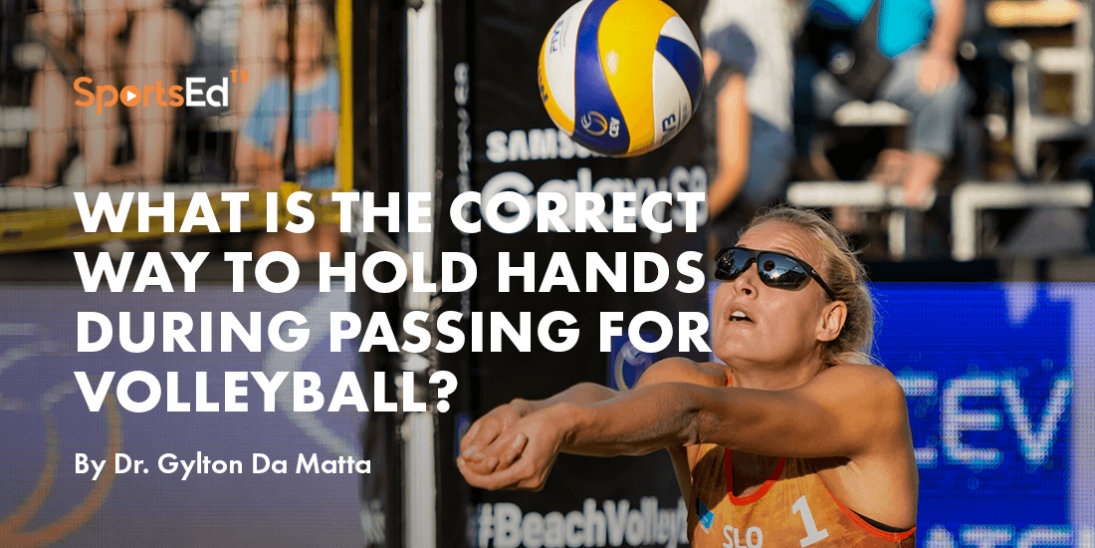

After practicing the ready position stance and acquiring good spatial coordination (personal space) in relation to the net and possible trajectories of the ball (serves flights), the player must practice their passing grips that could be adopted in every direction and possible final position, which include at their neutral zones or initial position.

Before 1998, passers would assume a very low stance because serves would be performed at a higher angle because front row players could block the serve. But after 2000, because the trajectories of the serves changed because it was prohibited to block the serves, passers embraced the low trunk position with their legs slightly extended so the angle of their platforms would deflect symmetrically to the angles of the serves, which were flat and very close to the net.

Following the spatial coordination, spatial recognition, and technical kinesthetic training, then, passers can start passing the volleyball at the mid, low, and high levels. Passing stationary passes is the simpler way to progress to 50 cm (2-3 feet away) and then passing further if needed.

In an adaptation of the new rules of 1998, passers started to utilize their overhand patterns, alternating from the pass with the overhand set or using the palms of their interlocked thumbs, which I have called "crown" above the forehead. In the '80s and '90s, Dr. Karl McGown would use the "tomahawk" for the high serves, but I have adapted the use of two open hands interlocked by the thumbs to allow a soft and bigger surface area to contact and rebound the ball.

The position to be on serve-receive as well as the ideal individual technique to perform a pass needs to be deliberately practiced using predictability and distribution of practice that will lead to successful experiences in passing. The deliberate practice in passing is critical to developing confident passers since frustration and fear are the two major enemies of a passer to become an expert.

The volleyball literature recommends that the passer starts from the left and be trained to pass all variability and possible serves at that position. Thus, this creates the 6th passing task, in which a passer stays at P5 and receives serves from P1, P6, and P5 from the other side of the court.

The control pattern needs to alternate between short serve, serves at P7 (15 ft line), and deep serves. Serves also need to be randomly performed at the left and to the right side of the passer. I like to pass at the athlete and then make him/her move to the right or left, front or back, diagonally forward and backward.

Then, the passer needs to be in P6 and execute a series of predictable serves in all directions, like when he/she was in P5.

Then, the passer needs to move to P1 and receives serves from all possible origins, yet in a predictable manner. This is a simulation phase of learning how to become a proficient passer.

Then, it is important to go through the same practice disposition but using the overhand technique or the "crown." Again, he/she must go P5, P6, and P1. Only after this cycle is complete would I recommend that the passer go through real serves, which would also include a great deal of variability in floaters and topspin serves.

At this point, the passers should move into a "real game" situation by playing 1 v 1 with modified rules.

Then progress into the 2 v 2 modified game, followed by the 3 v 3. Pause… At this stage serve receive passes should be adopted through "team passing" formats and concepts. Remember this whole tactical and technique evolution should happen in a combined microcycle of two weeks in a basic period (pre-season).

Of course, every coach is entitled to their opinion, but in my view, at this stage, I normally alternate faster serves at passers with a direct application in 4 v 4 games, so passers start to gain much confidence and enhance their capacity to perform at higher levels.

In a matter of days, passers should be engaged in practicing in a 5 v 5 format and soon, be able to play with a full-court with the 6 v 6 offensive system passing with 3 or 4 players.

In the third week of practice, with patience and intelligence, every team should have 8 to 10 good passers with good skills to perform. Unfortunately, many coaches who believe that there are no drills to teach passers positioning might be ignorant enough to label and cut players because they might not know how to manage their players. However, with good technical expertise, deliberate practice, and playing to acquire the tactical development to perform at the highest level, every team should be able to develop multiple players with the talent to be successful at any level.

Pass it on!