Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Pressing Matters!

Long before today’s common challenge, “How much can you bench (press)?", the earlier lifting challenge was “How much can you press?” Through the end of 1972 weightlifters competed in three lifts: today’s snatch and clean-and-jerk were as they are today. But the first competitive lift was the press. In the early days of weightlifting competition, the press lift was a true test of a lifter’s upper body pushing strength.

Why are we even considering the topic of a lift erased from competition nearly 50 years ago? Using an old adage, the simple answer is, one is only as strong as the weakest link. In today’s weightlifting competition, without the press, the shoulders and triceps do not get much emphasis, while squatting and pulling muscles tend to dominate. Yet, the arms and shoulders are an important part of one’s overall physical development.

Adequate upper body pushing strength can be vital, especially for female and youth lifters. Speaking generally of physiological differences between the sexes, women tend to exhibit about two-thirds of the upper body strength of males. Youth lifters of both genders, often recruited at an early age in order to learn weightlifting technique and begin competition, may report for training not particularly well prepared for a strenuous sport such as weightlifting. Specialization in two lifts that do not emphasize upper body pushing strength may eventually highlight strength imbalances likely to result in lost lifts or injury.

How did we arrive at this junction? Perhaps a slight look back at the history of the press will provide some insights for new lifters.

Some History of the Press

Over time the press went through many changes. For Americans, the lift started as the military press (heels together, bar at about chin level, raised at the same tempo as the referee’s hand). On the Continent, pressing involved some body sway in order to get the lift started.

Soon thereafter, press rules were standardized to begin with the bar on the shoulders and clavicles, and the feet up to 12 inches apart. The bar simply needed to proceed upward in a continuous motion, without stopping.

In order for lifters to press the barbell in the straightest path possible lifters gradually took up a slight lean-back posture in order to push vertically without having to maneuver around the chin. The rules continued to require lifters to press slowly. This is how the other two lifts, the snatch and the clean-and-jerk, became known as “the quick lifts.”

Lax officiating of the press eventually permitted a slight lean-back posture, at the beginning or as the bar moved upward. Hyperextending the spine while under a heavy load was not considered particularly safe, but it did tend to increase the amount of weight one could press.

At one time the rules allowed for a maximum layback, or backbend, of 27°. However, officials were not issued protractors, so the amount of backbend was impossible to determine. Note that at this time the two side referees were truly on the sides of the platform and could visually assess backbend. By comparison, today’s set-up has all three referees positioned at the lifter’s front.

Some lifters rapidly developed the ability to lay back quite a bit. Many began to employ the incline press in their training, as the backbend vs. barbell angle was similar to that achieved in this otherwise bodybuilding exercise.

Those lifters that employed a great deal of layback often kept their head and line of sight straight ahead so the officials might consider the backbend not excessive. As judging became rather inconsistent, we saw political fights develop over the judges’ decisions to pass or fail a lift. These were Cold War days and often resulted in meet-delaying protests to the Jury of Appeals. Remember, at the time, these lifters had nine attempts (three lifts, three attempts each), so meets often lasted well into the night.

The International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) periodically tried to regain control over the press, but technique became ever looser. The modern press was not unlike a push press, or a jerk without foot movement. Some lifters started in a bowed position and quickly launched the barbell upward by straightening up at the referee’s signal to press, followed by dropping back into a layback position. Other lifters awaited the signal in an erect posture, but quickly executed a near full-body effort to get the bar moving off the shoulders, then lay back. Toward the very end of the days of the press we frequently saw lifters using large, neoprene (think wetsuit) knee sleeves that visually hid the amount of knee flexion and extension employed to elevate the barbell.

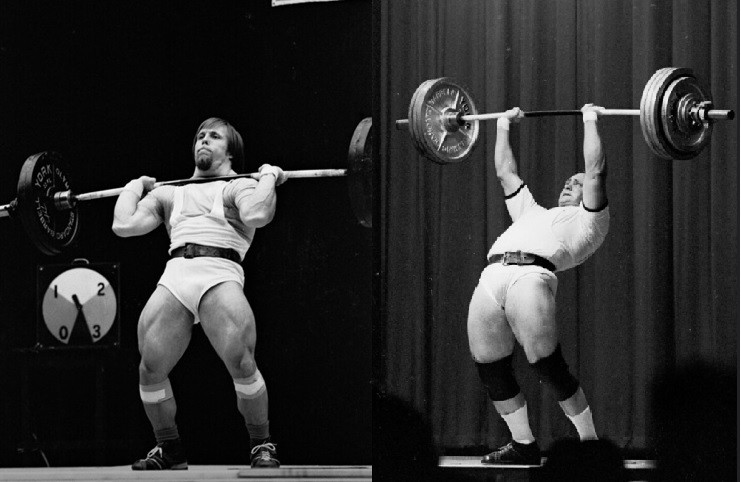

Bruce Klemens Photography. From the 1972 USA Olympic Trials, Photo 1 shows the slight, but quick, knee bend after the signal to press was given; Photo 2 shows the backbend used to “catch” the bar at near arms’ length with minimal pressing involved. Between 1 and 2 the lifter snapped to a vertical position that launched the barbell upward.

Check online footage of lifters in the early 1970s to see the amazing speed with which the barbell went to arms’ length. The famous Soviet superheavyweight, Vasili Alexeyev, became the first human to officially jerk 500lbs at the 1970 World Championships. A year later, at the World Championships he pressed 507lbs (and jerked only 518lbs!). The press had become another quick lift.

The press was on the political chopping block at the 1968 Olympics. According to Iron Man Lifting News a motion to eliminate the press from competition failed in a vote of 24 to 21 (reported elsewhere by John Fair as 27 to 23). Immediately after these Games several American lifting publications wrote of a renewed dedication to strict rule enforcement. However, press technique continued to loosen. The press finally died at the 1972 Olympic Congress in a 33-13 vote.

Why Press Today?

In the days of press competition lifters spent about 40% of their training focused on this lift. Needless to say, a reduction of this amount of training allowed lifters to rapidly improve performance in the remaining lifts.

Does pressing (in any form) play a role in the today’s training program? Sport scientist Bud Charniga (SportivnyPress) has written a thought-provoking piece, More About the Jerk, on his website. He does not suggest a total avoidance of pressing movements, but he considers it a mistake to prioritize pressing. He’s right, lifters with strong upper bodies may try to “muscle up” a jerk. The jerk is really an explosive lower body movement. Depending on the arms and shoulders to elevate the weight usually results in a press-out violation of the technical rules.

Of course, we’re not talking here about practicing the convulsive press, circa 1972. The upper body pushing muscles are strengthened by engaging in strict press performance.

There is no logical reason to totally avoid pressing movements. Several high-ranked national lifters I have interviewed in recent years claim their coaches place very little emphasis on pressing. Some coaches apparently advise against pressing or fail to train at an intensity great enough to cause improvement.

A few years back we heard about Chinese lifters doing handstand push-ups as part of their training. This exercise is a favorite of CrossFitters, although some of the convulsive moves exhibited at competitions may remind viewers of the final days (“anything goes”) of the press.

Opinion only, but my impression has been that one reason so many CrossFit females have done well in our sport is that they bring a higher level of basic strength to the platform compared to many who arrive at the platform through other avenues. Some form of pressing makes sense for all weightlifters. This might be the press (many varieties, either standing or seated), the bench press (I encourage a jerk-width grip and keeping the elbows near the sides), or the incline press. Bodyweight exercises such as handstand push-ups or parallel bar dips can prove valuable (and be fun).

Fitting Presses into Your Workout

When I served as USAW national coach (1981-84) the Olympic Training Center resident programs included pressing as a 10-12% portion of exercise volume. Push presses were not included here, as these were tabulated as a C&J exercise.

Take, for instance, a 1500-repetition preparation month. Pressing (standing, seated, barbell/dumbbell, bench, incline, etc.) consisted of 150-180 reps (counting only intensity efforts above 60% of one’s snatch PR) to be performed over four weeks. That’s about 40-45 press reps in a week, usually positioned in two of the week’s many workouts. Not much emphasis, but enough to strengthen the upper body pushing muscles.

Switching to a contest month four weeks out from an important meet, overall volume was reduced while intensity increased. We kept an emphasis on pressing for those with a tendency toward weaker upper body strength. The aim was to have all of our (male) lifters capable of a strict press with a load greater their bodyweight, ideally closer to their snatch max.

Due to anthropometric differences, not all lifters press well. Two-time USA Olympian Derrick Crass, capable of jerking 215kg, never achieved a 90kg press during his time at the OTC. His efforts did result in frequent laughs from his teammates as he struggled to press the barbell overhead.

Where to from Here?

Does holding a heavy snatch or jerk overhead present a challenge? Do jerks that otherwise make it to lockout crash back to the platform before recovery? Evaluate upper body pushing strength and whether or not improvement in this area might be beneficial.

To repeat, there’s no need to specialize in pressing actions, but a little work here can pay great benefits where we really want it: in our total. A few sets of well-targeted pressing each week does not require more than about 15 minutes of training time.

If upper body pushing strength is a weak link, the addition of a few sets may solve this challenge. Then it’s time to look for the next one!