Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

Pulling from the Hang: What’s It All About?

SportsEdTV Weightlifting is committed to bringing athletes, coaches, and parents pro-level Weightlifting education videos and blogs for FREE. All levels, anywhere, anytime. Check out our full instructional library and sign up to join our Weightlifting community.

According to the 2020 edition of the International Weightlifting Federation’s Technical and Competition Rules and Regulations, a lifter may not pull from the hang. Specifically, in Section 2.5 Incorrect Movements, we find rule 2.5.1.1: “Pulling from the hang, defined as: stopping the upward movement of the barbell during the pull.”

Why does this rule exist? In the past, the English weightlifting term hang, perhaps not well known to international audiences, begged for a definition. But for more than a century we have known the barbell cannot arrive overhead or on the shoulders in a multi-stage manner, such as the old continental style popularized by lifters residing on the continent, e.g., Europe. They pulled the bar to either the thighs or the weightlifting belt where they paused before effectively employing the lower body to produce a strong “second pull.”

We find under Chapter 2 (The Two Lifts) a general description of the snatch (2.2.1) and the C&J (2.3.1). Both sections have for many years stated that “The barbell is gripped, palms downward and pulled in a single movement from the platform…” and “During this continuous movement upward the barbell…”.

Pulling from the hang includes stopping the upward movement of the barbell which is clearly against the rules. Why is there a separate rule dealing with lifting from the hang? How and why did this rule ever come to be?

A Look Back

Bob Hoffman’s 1939 book, Weight Lifting, lists Lift No. 35 as the Two Hands Dead Hang Snatch. A lifter is instructed to stand erect with a barbell, then lower the weights to a location other than the platform. Thus, the hang is simply any barbell location other than on the platform. Hoffman mentions some lifters like to lower very close to the platform, while others prefer to lower only to about knee height.

“The object of this lift is to develop a stronger pull, a better and higher second pull,” Hoffman writes. Despite today’s common habit of dropping the bar back to the platform on every rep, building a “better” second pull with hang repetitions was popular in the past and remains so with insightful lifters today.

Snatches and cleans are very popular with many strength and conditioning coaches. They often include hang versions, so athletes are not required to start with the barbell on the platform. Most S&C coaches reference weightlifting’s explosive second pull as beneficial to these non-lifters, but often the hang position utilized is unlikely to produce the same type of peak power exhibited by weightlifters.

A Better Way Forward

Many of today’s lifters fail to recognize the benefits of lifting from the hang. It is common for lifters to perform a first rep of a snatch or clean, drop the bar to the platform, reposition, and perform another full repetition. Little consideration is given to the benefits of lifting from the hang. Grip and lower back fatigue, along with a consistent hang posture, are challenges for some. The use of pulling blocks, rather than lifting from various hang positions, is often a preferred manner of executing these derivative lifts. However, not everyone has access to proper pulling blocks, so lifting from the hang is a valuable alternative.

The SportsEdTV weightlifting library provides free video instruction on how to learn to snatch and clean from the hang position. This top-down method of instruction is really the best way to learn these lifts since the initial focus is only on the second (most explosive) pull. Once learned, the powerful second pull remains part of any snatch or clean.

Following Hoffman’s advice, we offer a “high” hang position and a “low” hang position. New lifters progress from high to low over a series of training sessions. Check out these videos:

SNATCH

CLEAN

More to the Story

Remember, this hang rule has been around a very long time, longer than most of us. As the sport evolved, so have the weights lifted, the equipment, and the rules. Aside from the obvious requirement to pull in a single motion, what, if any, advantage would be realized by lifting from the hang?

During my time as the national coach for USA Weightlifting, I supervised resident athlete training at the US Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs. This normally involved about a dozen male weightlifters. In the 1970s I had been heavily influenced by the teachings of Carl Miller, National Coaching Coordinator. Carl was a fan of lifting from blocks, so one of our early OTC construction projects was the development of decent lifting blocks. Some earlier models (see Photo 1) had been created prior to my arrival, but I wanted a more solid, easily adjusted block system.

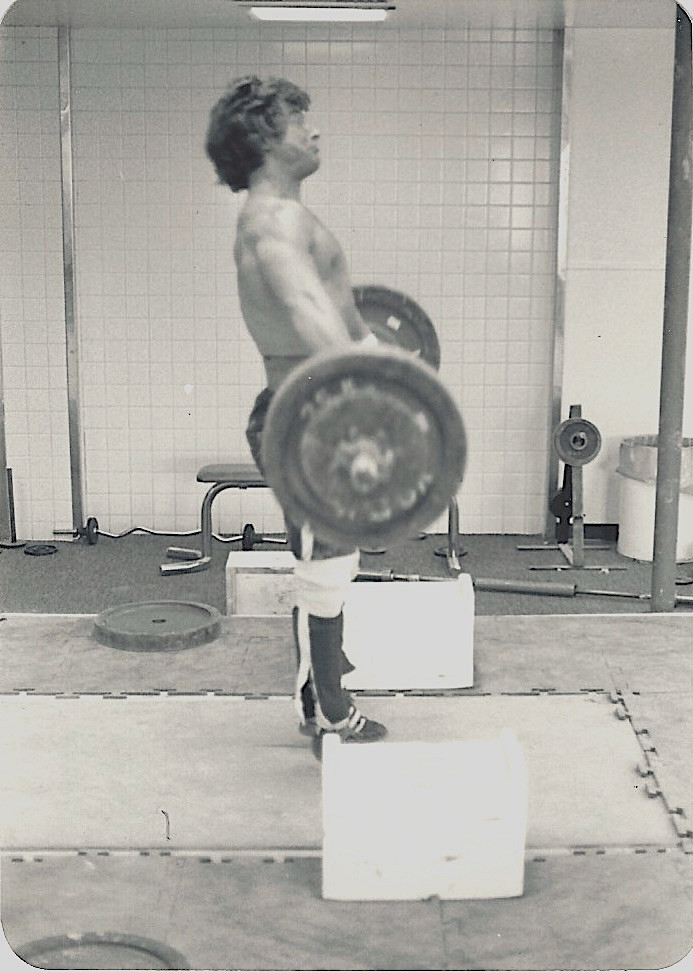

Kevin Winter pulling for the first-generation OTC blocks that were all the same size and could not be adjusted to different heights.

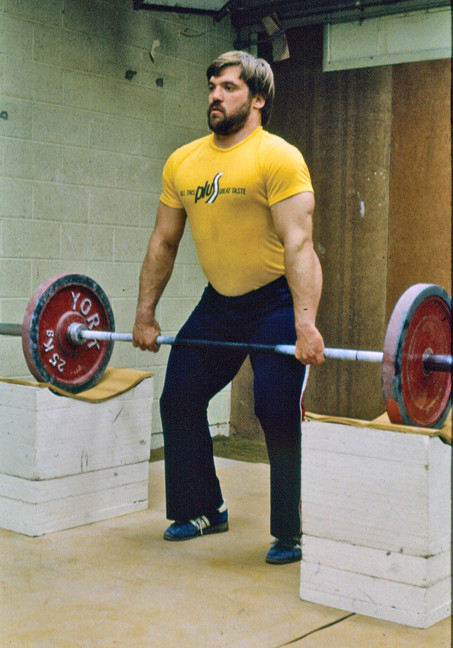

Placing the barbell and the lifter in the correct high block posture for an explosive second pull, a coach can easily achieve what is now commonly referred to as the power position. With the barbell near the hip crease (snatch) or mid-thigh (clean) (see Photo 2) the lifter’s ankles, knees, and hips are flexed. From here the lifter quickly pushes the barbell upward with the stronger lower body.

Derrick Crass shows the proper position for an explosive second pull in the clean. These blocks included a more secure top, along with a solid main body with adjustable bottom boards.

Check the SportsEdTV weightlifting library to see the correct posture when employing high blocks.

Over my years at the OTC, I coached at least three lifters who snatched more from the high blocks than they could from the platform. Of course, the use of blocks is not permitted in competition. And, lifting from this position really calls for the use of pulling straps, another advantage lifters cannot utilize in competition. But I wondered, what was going on here?

Knowing the lifers and their backgrounds I quickly concluded that 1) they had learned to snatch from the platform and 2) they did not effectively utilize the lower body to push the barbell upward when lifting from the platform. Lifting from the power position was a foreign concept for them, but once experienced, performances improved.

This same reaction is seen during the filming of the DVD, Explosive Lifting for Sports. Our models were relatively unfamiliar with this high block position that allows for such a great second pull. I had the same experience with the first Dartfish weightlifting instructional videos, when a member of a USA junior world championship team simply could not get his head around how to snatch, from a proper power position, a 60kg barbell on high blocks.

Since these were all experienced lifters, with years of training and competition under their belts, the chance of effectively altering technique to take advantage of a solid power position was a challenge.

We see this today in the massive number of lifters that think the hips are to be forcefully driven into the barbell for an effective second pull. Nothing could be farther from the truth; such an action directs the barbell forward much more than an effective second pull where peak force measurements should occur.

What we really want is a barbell-carrying action. In watching frame-by-frame video it is clear that the masters of proper technique “carry” the weights for several frames while the powerful lower body extends upward.

OK, But Still, Why This Rule?

Now for the final part of the story. Let’s look back to the days when we used iron discs and could not drop weights from overhead as is so popular today. Consider also, those performances involved lighter weights, even at the record level.

It’s important to consider that prior to the early 1960s the barbell could not touch any part of the body before arriving overhead (snatch) or on the shoulders (clean). Today’s power position did not exist. Lifters simply extended the hip joint by straightening up and rising on the toes. It was also fairly common to see lifters flex their elbows (bend the arms) prematurely during the second pull.

While lifting in this style it was possible for a lifter to miss a snatch, but rather than simply dropping the barbell to the platform, he (no female lifters in the “old” days) might hold onto the bar and quickly stand erect, catching the weights as in a multiple rep set, then lower the bar to a hang position and complete the lift. Of course, such a lift would be turned down by the officials, but still, this is an impressive feat.

Did it ever happen? The venue for the 1957 US National Championships was the Peabody Auditorium in Daytona Beach, Florida. This site is across the street from the Ocean Center, the site of the 1987 inaugural IWF Women’s World Weightlifting Championships. Coincidentally, I crossed the same Peabody stage a few years after the Nationals to receive my high school diploma.

Anyway, the then 82.5kg (181-3/4lb) category featured three world-level American lifters, Tommy Kono, Jim George, and Dave Sheppard. The October 1957 issue of Strength & Health Magazine features a comprehensive write-up of this meet by Bob Hoffman, who writes, “Incidentally, when Dave (Sheppard) missed his 285 (pounds, approximately 130kg), he lowered it to the hang position and made it easily, laughing and winking at the audience—which proves a point. I have long maintained, that his position is wrong, and his S-curve theory is a bad one when he can dead-hang snatch weights he cannot lift in the regular position.”

While Bob’s comments on the S-trajectory in the snatch and clean were later proven to be incorrect, it does reinforce what I saw nearly 30 years later with lifters that could snatch more when properly placed in a (now legal) power position than from the floor.

So, there is the complete story. Some lifters can lift more from the hang than they can from the floor. For years the rulebook simply said, no lifting from the hang, with no further explanation of what this meant. More recent editions have opted to explain this rule to those unfamiliar with the term, but in so doing they have spelled out only that there shall be “no stopping of the upward movement.”

It’s impossible to snatch or clean from a hang position without either stopping or lowering the barbell, both of which are existing, long-time rules. This rule against lifting from the hang could easily be discarded.