Weightlifting

Welcome and thanks for visiting...

It’s a Long, Slow Climb to the Top

We have known for many years that a talented weightlifter requires about 10 years of steady training and competition in order to reach the highest international victory podium. In some other sports, particularly team sports or some of the Winter Olympic Games disciplines, an athlete may make the podium with much less than 10 years competitive experience.

But our sport is a different story. Simply stated, our sport is not one for those seeking instant gratification. For the lifter aiming to compete at the Olympic Games, he/she needs to be both physically and psychologically prepared for the long haul.

This timeline may present a challenge for eager coaches, or parents, when working with young athletes. Many push for quick results, something easily accomplished up to a point, with beginners. As has been previously written in these pages, the continued effort to create elite competitions such as the Youth Olympic Games or the Youth World (or regional) Weightlifting Championships may end up being counterproductive. This may contribute to weightlifters leaving the sport, via burnout, before they can achieve maximal results, typically in the 20s. In other words, an increased focus on excelling at younger and younger ages can simply translate to promising athletes departing the sport early, long before they might have made their best performances.

A few years back, when such details were easily available, USA Weightlifting had noted that percentage wise, the largest group of athletes that failed to renew their memberships came between the youth and junior categories. The second largest drop-off in renewals was from junior to senior ranks. If we’re talking here about losing those that only competed for fun, no problem. But this suggests that many, including perhaps promising lifters, quit well before they achieve optimal results.

The recent Winter Olympic Games headlines have been chock full of stories related to too much, too soon. This is easily explained in sports such as women’s figure skating (and gymnastics), where experts seek to optimize power to bodyweight ratios by raising athlete performance through youth ranks before normal hormonal changes occur. Such changes can preclude an older participant from performing some of the fantastic jump and/or flip performances we have become accustomed to viewing.

Weightlifters at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games

An interesting paper entitled Competitive activity of weightlifters at the XXXII Olympic Games 2020 in Tokyo: results and prospects appeared in Health, Sport, Rehabilitation, 2021, 7(4):69-83. Some very good data are presented within, although some details can be challenging to interpret.

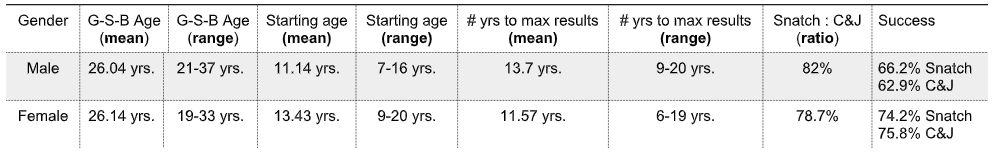

The authors report on a subject pool that consisted of the 10 best lifters in each weight category and gender, a total of 140 lifters. But most of the findings relate to the “winners” which should be interpreted as the medalists, not the category winner. Also, “maximum results” is interpreted to mean the lifter’s Tokyo performance that resulted in winning a medal. Although the authors divided the seven bodyweight categories in three sections, those comparisons are not reflected here. Check Table 1 for details:

Table 1. Selected characteristics of Tokyo 2020 Olympic Weightlifting Medalists.

Highlights

Note that these data suggest, at least at the Tokyo Olympics, that some women achieved maximum results after fewer years of training than men. USA’s Katherine Nye, for example, took only six years to get to this level, beginning lifting at 16 with a background of gymnastics and CrossFit. Emily Campbell (UK) achieved her results after only seven years of training. Olympic Champion Maude Sharron (CAN) began lifting at 19 but came to the sport with a background of circus and CrossFit.

The authors highlight the fact that, “Moreover, most of the athletes who began to practice at the age of 15-16 came to the sport substantially prepared, i.e., from other sports.” Here again is the message, prepare the complete athlete (including the learning of effective weightlifting technique) at an early age, but wait to specialize in weightlifting until adolescence.

Not surprisingly, the most successful weightlifting team in Tokyo was China, with eight lifters, eight medals (100%). Teams from Italy, Indonesia, and the Dominican Republic fielded only three lifters on their roster, but for each, two won medals (67%). Several countries fielded larger teams but secured no medals.

Final Thoughts

What is often lost on some coaches who work with talented young athletes is that while it will take eight to 15 years to reach the Olympic level, this does not mean early specialization. Note that in Tokyo, only one teenaged lifter, Windy Kantika Aisah (IND, 49kg) was on the podium.

If the aim is to excel and win Olympic medals in weightlifting, the formula includes learning the lifts at an early age. This is followed by age-appropriate competition, along with regular participation in other sports. But “going to the bank” too often, at too early an age, may be detrimental to optimal performance.